Translator of Gloria by Andrés Felipe Solano

By Michele Mathews

Andrés Felipe Solano’s Gloria is a layered, intimate novel brought into English by longtime collaborator and translator Will Vanderhyden. In this interview, Vanderhyden shares what drew him to the book, the challenges of capturing its unique perspective, and what he hopes readers will take away.

What initially drew you to Gloria, and how did you come to translate this particular novel?

WV:I’ve known Andrés Felipe Solano and have been a big fan of his work for more than a decade. Over the years I’ve translated samples of several of his books, which his agent would subsequently pitch to different publishers, hoping to find a home for his work in English. Gloria is his most recent novel, and so, like with his previous books, I translated a sample that his agent sent to publishers in the U.S. and U.K. And Dan López, a great editor at Counterpoint Press, ended up acquiring the rights, and he contracted me to do the translation.

What drew me to Gloria and to all of Andres’s work is his unique sensibility as a writer: he has an elegant and understated style, where not a word is wasted and everything is layered with meaning; a journalist’s eye for descriptive detail and an uncanny sense of pacing that allow him to efficiently construct character, mood, and atmosphere; and an interest in crafting intricate narrative structures that refract the specific and personal into the timeless and universal. This sensibility is present throughout Andrés’s work, but I think Gloria is its most distilled and accomplished expression to date.

What were some of the biggest linguistic or stylistic challenges you encountered in translating Gloria?

WV: Getting the narrative perspective to feel right was one of the bigger challenges. The story is told in a close third-person, from the perspective of Gloria’s son, self-reflectively using a day in his mother’s life as a prism to try to understand her by turning her into a character and telling her story.

Andrés makes inhabiting that perspective seem effortless, zooming in and zooming out, jumping around in time, moving fluidly from Gloria’s interiority to subtle details that evoke her particular time and place in history to meta comments on aspects of the story he’s constructing as he’s constructing it. And he does all of this in a way that’s both intensely grounded and mysterious—there’s no hand-holding, no superfluous exposition.

It’s a lot to balance, but getting it right was fundamental to making the book work, so I spent a lot of time thinking about that POV and did my best—over the course of multiple revisions—to make it come alive in English.

Were there any particular passages or moments in the book that were especially rewarding—or maddening—to translate?

WV: Nothing that was especially maddening. There were many rewarding moments— beautiful lines, insights, impressive narrative maneuvers—but without context, without over-explaining or spoiling elements of the story, it’s hard to be specific.

I guess I can say that I really love the beginning, how, within a few pages, Andrés is able to evoke Gloria’s tumultuous inner life and the heightened tension of the day when we meet her, to ground us in a particular time and place, and to introduce the narrative conceit of the POV mentioned previously.

Here’s the opening passage:

“She has never smoked and may never light up a cigarette, but today, which I decide to imagine bright and bustling, she should, she should take advantage of her boyfriend being late to slowly inhale the smoke, aware of how her lipstick is leaving a mark on the filter, the nervous pressure of her lips giving it a slightly oval shape. Inside that silvery blue cloud of smoke, the wait is less agonizing, more bearable, as they say of certain afflictions, because that’s what it is, a disquiet she discovered upon waking that morning, earlier than usual, when the light slipped softly in through her room’s window and she couldn’t yet hear animals knocking over bottles on that street corner in Queens. When she first opened her eyes, she’d even felt hopeful, reentering the world without fear. It usually takes her a little while to come to terms with what it is to be alive and awake, a few minutes to tentatively break the waters of sleep, but today is different, because today is a day that should last forever—that is, if Tigre ever bothers to show up.”

Getting that feeling dialed in in English was very rewarding and gave me a strong sense for how to approach the rest of the book.

How do you approach preserving an author’s voice, especially one as distinctive as Solano’s while still creating a fluid reading experience in English?

WV:When I’m translating, I think a lot about trying to make the feeling I get when I read the text that I’m writing in English mimic the feeling I get when I read the Spanish text, to use the tools of English and whatever skills I have as a writer to create an analogous experience that’s ultimately subjective, but that I hope will play on other readers’ nerve endings the way it plays on mine.

So, for me, it’s less about preserving the author’s voice and more about finding a way to recreate my own version of it. My process generally involves, in early drafts, following my intuition and letting myself make the choices that feel right in the moment, and then going back and putting the text through a pretty intense process of revision. And it’s usually through that process that I’m able to hone in on and fine-tune my English version of the author’s voice.

What was your working relationship like with Andrés Felipe Solano during the translation process?

WV: Like I said, I’ve known Andrés for a long time and we’ve worked together on multiple projects, so we have a very comfortable and affable working relationship. Typically, the process involves me getting to a place where I’m pretty happy with the translation and then turning it over to Andrés with a list of questions. He goes through the text and answers my questions and offers edits where appropriate. His English is quite good and he’s a translator himself, so we have a lot of trust in and respect for each other, which makes the process easy and fun and enlightening.

Gloria is known for its layered, introspective, and at times disorienting narrative. How did you balance clarity with fidelity to that complexity in English?

WV: I think this gets back to what I was saying about the POV. And so I guess I’ll refer back to that previous answer and just add that getting the POV to feel right is how I was able to strike the balance you mention in my translation. And the way I was able to get the POV to feel right was through revision.

How do you deal with ambiguity in the original text—do you try to clarify or preserve it?

WV: If something is ambiguous in the original text, I generally try to preserve that ambiguity. I try not to introduce ambiguity that isn’t there in the original, if I can avoid it. But generally, I trust that readers are smart and that ambiguity is part of what makes fiction great.

Do you see yourself more as an interpreter, a co-creator, or something else entirely when translating fiction?

WV: I don’t really buy into one particular metaphor for what I’m doing when I’m translating fiction. I think they’re all useful and inadequate in different ways. As I’ve said, for me, translating is about trying to recreate the feeling that I have while reading the Spanish when I read my English version. This is necessarily a subjective experience, and I can only hope that what feels right to me resonates with English-language readers.

How do you navigate the line between staying true to the original and ensuring the translated version reads smoothly to an English-speaking audience?

WV: Every translation is different and makes different demands of the translator and finding that balance you mention is always key, but I think, for me, again, the answer here is revision. For me, there’s usually a moment in the process of revision (sometimes it comes quickly and other times it’s more hard won), where things start falling into place and really clicking and the text starts to come alive in English. For me, it’s the most gratifying and creatively stimulating aspect of being a translator and probably the reason why I do it.

Are there particular things you hope readers take away from this translation?

WV: I hope that all the things I’ve mentioned about Andres’s style and sensibility come across in the translation and that readers enjoy the book and find it beautiful and moving and deep.

How do you choose which books to translate? What do you look for in a project?

WV: Generally, I look to translate books that I love to read and want to write. So, I follow my tastes as a reader and my interests as a writer. Of course, this “job” is always a hustle, so, when presented with an opportunity that might not seem a natural fit at first blush, usually I’m grateful for the opportunity and happy to take a stab at it anyway.

Are you currently working on translating any other works by Solano—or other authors you’re excited about?

WV: I’m not currently translating anything by Andrés, but I know he has a new project he’s working on, which I can’t wait to check out whenever he’s finished.

I just finished translating a book by Rodrigo Fresán called Mantra, and I’m in the middle of translating Fernando Arumburu’s El niño. This is the sixth novel of Fresán’s I’ve translated and the first of Arumburu’s. I’m pretty excited about both books and authors.

Through Will Vanderhyden’s translation, Gloria becomes not just a story of one woman’s life, but a testament to the delicate, intricate art of carrying a writer’s vision across languages. Vanderhyden’s deep respect for Andrés Felipe Solano’s sensibility—his precision, atmosphere, and layered narrative—shines in his thoughtful approach to voice, perspective, and ambiguity. As Gloria reaches new readers in English, the novel invites us into its richly intimate world, while also reminding us of the translator’s quiet but essential role: bridging distances so that literature may resonate universally.

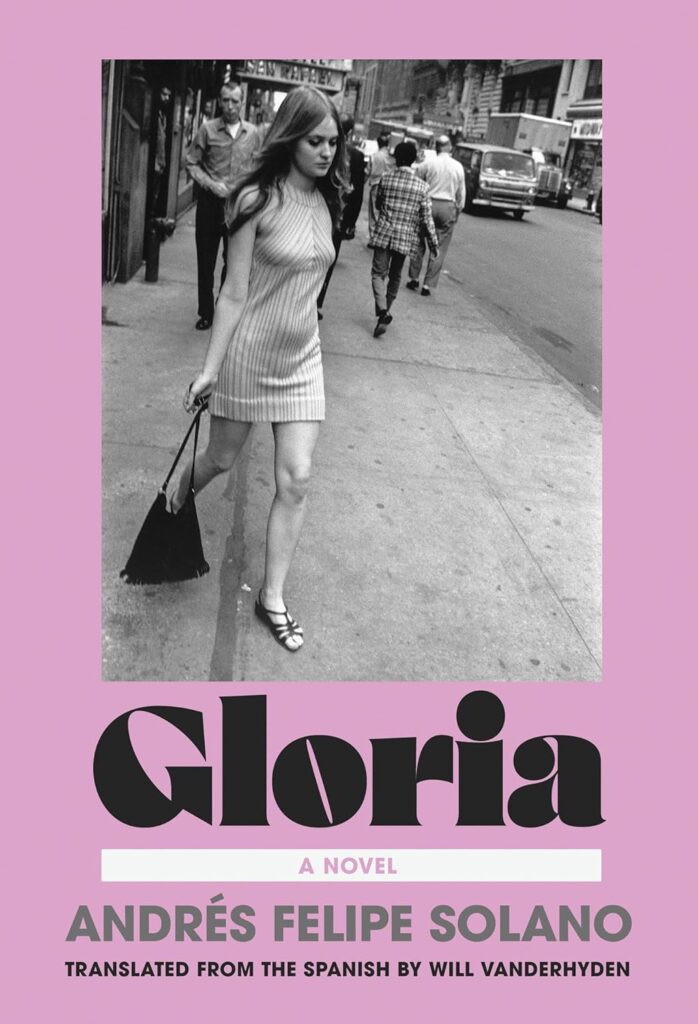

Gloria

Andrés Felipe Solano, translated by Will Vanderhyden

Centered around a real-life, historic concert at Madison Square Garden, this wide-ranging and nostalgic novel spans two continents and five decades as it charts the interlaced lives of a mother and son in New York CityIt is a bright spring Saturday: April 11, 1970. The famous Argentine singer Sandro is about to become the first Latin American to perform at Madison Square Garden, and Gloria will be one of the lucky attendees at what will be a legendary concert. At just twenty years old, the young woman walks through the electric streets of New York City full of hope and possibility. The disturbing images she recently encountered at her job at a photographic laboratory, the trauma of a father who was murdered when she was a child, and even the long-term prospects of her relationship with Tigre, her irascible boyfriend, are problems for another day. This day should be perfect and should last forever. Which it will, in surprising and unexpected ways. Five decades later, Gloria’s son reflects on his mother’s life and realizes that their formative years–imprinted as they are by sojourns in New York at exactly the same age–are a bridge between generations that draws the pair closer through a shared sense of longing and potential. A novel of mothers and sons spanning New York City, Colombia, and Miami, Gloria is a sophisticated and daring excavation of a woman’s life that asks us to consider how the choices we make in our youth reverberate throughout our possible futures.