By Christina Consolino

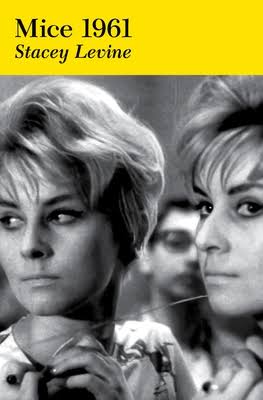

Stacey Levine is no stranger to writing. She is the author of “five books of uniquely original voice-driven fiction” and has had work featured in The Brooklyn Rail, The Fairy Tale Review, The Iowa Review, Tin House, and Yeti, among others. Her stories have been longlisted and shortlisted for multiple awards, including The Story Prize, The Washington State Book Award, and the PEN Award. She was also the recipient of a Genius Award from Seattle’s The Stranger newspaper. In this interview, she talks about her forthcoming novel, Mice 1961, which will be released March 19 by Verse Chorus Press.

Mice 1961 “recounts a pivotal day in the fraught relationship of two orphaned sisters through the eyes of their obsessively observant housekeeper.” Housekeepers have often been viewed as secondary, even inferior, by many in society. Can you comment on your choice to have Girtle serve as the point of view character?

SL: Girtle evolved as I worked with her. She’s a complex person who comes from a disturbing place. Through the course of the book, she’s happy, even elated, to have left that place and to have found the sisters. In the “now” of the novel, which is a few months during 1961, she’s about 30, but younger than that emotionally, and she tolerates unkindness amazingly well. Her life and independence have just begun—the upshot is that her future is ahead of her and outside the novel’s perimeter.

A descriptor like “obsessively observant” intrigues me. What makes Girtle that way? Do you think it helps or hinders her ability to take care of the girls?

SL: The older sister, Jody, bosses poor Girtle around like hell and worse, and does the same to Mice, the younger sister. Though Girtle is meek, one of her strengths is her passionate habit of close observation. It’s sort of all she has.

Being observant certainly is an advantage for writers—is that a descriptor you would use for yourself?

SL: If I’m a novelist, it better be!

Writer Garielle Lutz said of you and your work, “Few writers are ever this alive to language and this tender toward the lot of the vividly different among us. I am in awe.” Would you consider yourself “vividly different”? How far do we have to go as a society to celebrate those who are “vividly different”?

SL: I am not vividly different, no, but I’m a little bit different, sure, just as many people are. Of course we should rejoice in difference. But in a better world, we would not need to do that because there would be no cruel emphasis on difference.

There’s something broken and unevolved about humans where we habitually group off and exclude other people. Mice 1961 is about that, mostly. The younger sister (whose nickname is “Mice”) has the genetic condition of albinism and is bullied pretty badly by the whole neighborhood, even elders! So as the writer, it was my job to explore that.

Let’s talk a little about the two sisters, Jody and Mice. Did these characters arrive fully fleshed as sisters? What made you concentrate on a story about two sisters in particular? What about the sister bond is so appealing to write about?

SL: For me, writing’s 90 percent process, meaning that you write from the dust up. In writing, you discover the particulars. No, they did not arrive to me developed in the least! They were dinky little dolls when I first saw them. I knew their potential. It took me a long time to lay down the minutia of their relationship. Losing their mother has warped their relationship, and it’s horribly co-dependent. But there’s a positive side to their closeness.

In an interview with Jeff VanderMeer, you stated that your stories often start from “evocative music” or “moments of human connection.” What sparked the idea for Mice 1961?

SL: I was sitting on my couch and viewed a Facebook photo of a friend wearing a striped, blue sailor

twentieth century. I thought about the passion of the pro-Castro supporters who wanted to take their country back from a dictator, and conversely, the anger of the pro-Batista supporters to crush Castro. That was how the book started, though it veered away from the political struggle and now focuses on the sisters. The novel does spend some time on the tensions that arose in South Florida just before the Bay of Pigs incident.

How much research did you have to do in order to capture the world that Jody, Mice, and Girtle live in?

SL: I did a lot of research. I received a small grant from Seattle Artist Trust to travel to Florida and visit Miami’s older neighborhoods for a few days. I did lots of notetaking and got a sense of the old neighborhoods’ layouts and all the crazy canals winding around the business districts. I also watched any old movie I could find set in 1960s Miami.

The novel’s themes include separateness and otherness, which should resonate with many readers. In today’s world, instead of seeing how alike we are, many concentrate on the differences, reinforcing the idea of someone as “other,” often in a derogatory manner. What message are you hoping your readers will take away with a focus on these themes?

SL: I do not espouse one particular message in the book, though I think the book embodies a tender feeling. Aside from that, the story asks questions. There’s a branch of philosophy called the Philosophy of Personal Identity that I’m fascinated with. It asks questions like If you are a wholly different person to what you were decades ago, what exactly has persisted in you between then and now? Or If we are all physically formed of the same fundamental elements such as carbon and oxygen, what precisely makes us different from each other? These kinds of ideas shaped parts of this book.

You’ve been writing for a long time. How have you evolved as a writer? How does Mice 1961 fit into your overall body of work?

SL: If you keep working, you can’t help but evolve. Mice 1961 is longer and may be more dynamic than my previous works, which often describe people or places that embody everlastingness—not too much change occurs. And also, before this, I’d never written a long, ongoing party scene!

Your work has garnered several distinguished awards. Is there anything you feel you haven’t accomplished but would like to do so?

SL: As I’m sure you know, literary fiction writers and poets write in order to be able to write, right? Well material recognition of some kind is very important for any artist, but the goal is really to be living the life and delving into work all the time vs. collecting acrylic award blocks. I’m the type who gets too nervous or anxious if I don’t have a project ongoing, a place where I can go and sit down and tinker.

What’s next for you?

sl: We live in an era of very bad, reprobate, and callous behavior. It’s like a common denominator. Wouldn’t it be nice to write about people and nations that are good and sweet to each other?

Mice 1961 recounts a pivotal day in the fraught relationship of two orphaned sisters through the eyes of their obsessively observant housekeeper. Will Jody be able to cope if her younger sibling Mice, subject to constant harassment in their community for her unusual appearance and habits, leaves home? How will their all-watching companion convey her fierce attachment to them both? When they cross paths with an unsettling stranger at a neighborhood party, all three women are driven toward momentous changes.

Set in southern Florida at the peak of Cold War hysteria, Mice 1961 is a powerful meditation on belonging and separateness, conformity and otherness.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the March / April / May 2024 Issue: Indie in Bloom.