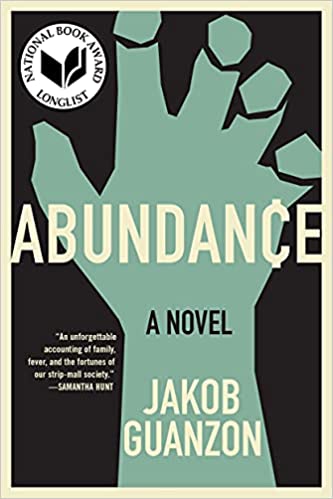

What happens when you take an ordinary event like a grocery run, add an impatient group of shoppers, and that journaling habit inspired by your mother? Well, for Jakob Guanzon those things turned into the writing and launching of his first novel, Abundance. In this tense narrative, an ordinary father, down on his luck, is faced with hardships as he strives to make a better life for him and his son.

Your debut novel! This is exciting. Tell us what this monumental event has been like for you.

JG: It’s bananas. I mean, how many kids who dream of being an astronaut ever make it to space camp, much less board a rocket to the moon? Before you catch this incredible break, the odds of ever getting published are stacked sky high, and the years of rejections but still writing into the void train you to expect disappointment. That said, it’s no easy feat to get my head around the fact that a book I wrote is out in the world, but it sure tickles me to try.

I’ve got to admit that it’s been pretty nerve-racking, too. Not in terms of critical reception or sales figures, though. I was really worried that scratching such an audacious goal off the old bucket list would inflate my ego to Hindenburgian proportions, only to crash me into a blaze of writer’s block. However, once the hullabaloo of the initial launch had settled, my first uninterrupted writing session in weeks proved that I still got the itch, and that’s humbling.

Reading your book reminds me of the movie the pursuit of happiness. What inspired you to write Abundance?

JG: As a huge Fresh Prince [of Bel- Air] fan, I’m ashamed to say I never saw that one. Quite a few friends suggested I watch it while I was writing Abundance, but I had to hold off. Other stories—whether in books or on the screen—have this cheeky way of weaseling their way into my own work during my initial drafting phases, so I’ve always got to proactively distance myself from similar works whenever I’m writing something new.

The original inspiration for Abundance came to me at a supermarket here in New York. The check-out line had come to a standstill. The other shoppers’ impatience behind me was palpable. When I peeked toward the register, I saw the culprit for the delay: a woman nervously sifting through a splash of loose change to pay for her groceries. She looked tired, the coins heavy in her fingers. Meanwhile, the indignant huffs kept gusting from behind me. Such an utter lack of empathy, it jarred me. Clearly this was a person who needed help, yet in that moment she was reduced to an object of scorn to her fellow shoppers, whose inalienable right to a seamless retail experience she’d infringed simply by being poor. To me, this felt like a rift that merited exploration through narrative.

In some ways, this book is a coming of age story as we alternate between Henry’s growing up years with his father and Henry raising his own son. Why was it important to you to capture both versions of the MC?

JG: While I’d originally conceived of this story as a day-in-the-life piece, the subject matter at the forefront began to feel too heavy. Glimpses into Henry’s youth and happier days seemed like an effective way to both offset this grim weight. There’s an intrinsic current of hope that runs through your conventional bildungsroman, and that youthful levity rubs up against the ickier realities of adulthood to provocative narrative ends.

Not only do the scenes of Henry’s youth allow for a more complex and humane reading of him as a character, but they also sow certain thematic seeds that get subverted later in the story. The big one for me was American optimism, which, in Henry, gets embodied as a naive form of hubris. In spite of how thoroughly acquainted he’s been made with life’s passive cruelties, he’s so prone to delusions of hope. He gets swept up into truly believing that things might get better for once, that this could finally be his big break, when both human history and contemporary data all indicate that, well, nope: social mobility is a thing of the past.

Tell us more about you. How did you get into writing?

JG: My ma gave me a journal when I was about eight years old. My folks were going through a divorce, which is messy stuff for anyone to process, much less a child, so she suggested I scribble down how I was feeling in those pages. It helped. It stuck. Writing has become a refuge for me, a quiet place where I can wrangle with my irrational emotional responses to the world’s havoc, and compress them into more manageable units of language.

Still, it took me quite a while to transition from clandestine musings to fiction. Storytelling felt out of my league. It’s one of those rare enduring technologies, implemented through the ages to transmit knowledge, foster community, and even rebel against the status-quo. That seemed like pretty serious territory for a moody kid like me to wander into, so for years I tried to mitigate my compulsion to write stories by focusing my energy elsewhere. I had bills to pay, validation to earn, and none of the drivel I was writing in secret would have gotten me close to either a paycheck or a friendly high-five. But eventually it became clear that writing was the only pursuit that gave me some semblance of meaning, so I might as well give it an earnest go before I die.

You use the amounts of money as chapter titles in abundance. Tell us how you decided on this unique detail.

JG: Economic hardship is nothing new to literature, but there was one excruciating psychological aspect of poverty that I felt had yet to be unpacked: that unrelenting awareness of your spending power, down to the penny. When you’re broke, it’s a figure that gets branded onto your mind because it dictates what you can access in society, which isn’t much. The poorer you are, the narrower your options get, which in a very real way undermines your agency, not to mention your human worth.

By titling each chapter with the exact amount of money Henry has in his pocket, I sought to convey this information in a way that was as inescapable for the reader as it is for Henry. Over the course of the novel, each expenditure or minor gain provides an external source of tension that presses down on the ostensible plot, which to some slight degree captures the perpetual crush of poverty on the individual.

Who are a few of your favorite authors, and how do they influence your writing?

JG: There are too many brilliant authors working right now, pushing language against fresh thresholds as well as bringing historically underrepresented stories into readers’ lives. Writers like Carmen Machado, Justin Torres, Deb Olin Unferth, and Mark Doten pop into my mind first, probably because each one of them has forged their own unique style that’s playful on the page, yet still manages to tap into zones of devastating pathos. That’s the type of literary trapeze act that dazzles me most. Such stylistic inventiveness and unexpected emotional gut-punches keep me on my toes as a reader, and also challenge me to never settle for easy outs as a writer.

What’s next for you? Do you about the book have other books in the works? If so, what can you tell us about them?

JG: I made the mistake of starting another novel back when Graywolf acquired Abundance, about two years ago now. I’m happy (and quite relieved) to say that it’s finally reached the final stages of revision.

The working title is Paint the Devil on the Wall, which comes from an old Swedish idiom for “expect the worse.” It follows a triptych structure that cycles through three loosely connected characters who have wildly incongruous beliefs about how to effect progress. The first is a radicalized misfit who’s taken up a wildfire lookout post in the depths of the Sequoia National Forest where he can practice restraining hostages and assembling homemade explosives. The second is a Swedish environmentalist whose cold rationalism prevents her from sympathizing with her partner’s trauma. And the last is a celebrity philanthropist who’s the only one of the three that does effect significant social uplift, though his sole motivation is his voracious narcissism. It’s a wild one, and at the very least has kept me occupied creatively. Fingers crossed it’ll resonate with readers as much as the first book has.

About the Book

A wrenching debut about the causes and effects of poverty, as seen by a father and son living in a pickup.

Evicted from their trailer on New Year’s Eve, Henry and his son, Junior, have been reduced to living out of a pickup truck. Six months later, things are even more desperate. Henry, barely a year out of prison for pushing opioids, is down to his last pocketful of dollars, and little remains between him and the street. But hope is on the horizon: Today is Junior’s birthday, and Henry has a job interview tomorrow.

To celebrate, Henry treats Junior to dinner at McDonald’s, followed by a night in a real bed at a discount motel. For a moment, as Junior watches TV and Henry practices for his interview in the bathtub, all seems well. But after Henry has a disastrous altercation in the parking lot and Junior succumbs to a fever, father and son are sent into the night, struggling to hold things together and make it through tomorrow.

[cm_page_title title=”Continue Reading” subtitle=” Shelf Unbound”]

Article originally Published in the April / May 2021 Issue: Cover Stories.