BY ALYSE MGRDICHIAN

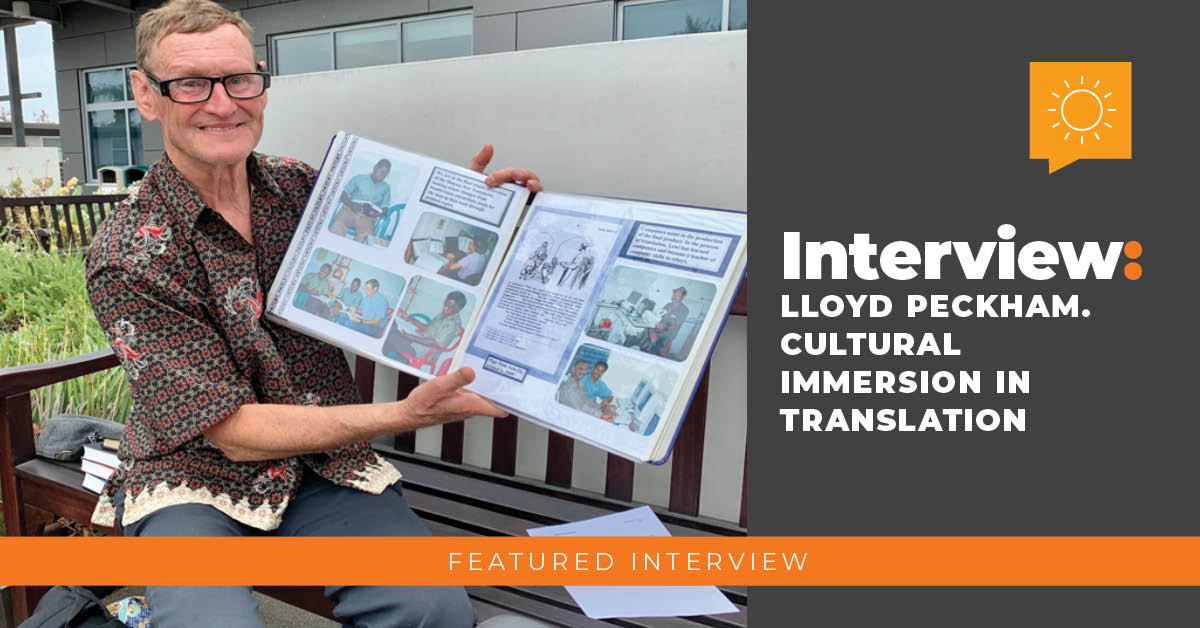

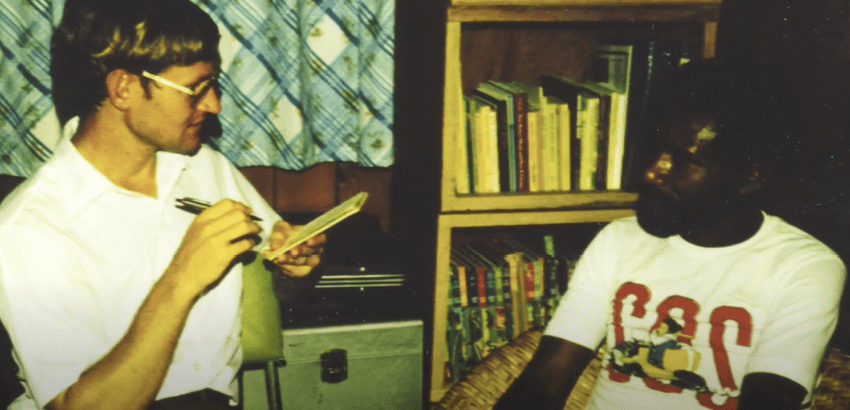

Translations come in a variety of forms and levels of complexity, whether they be poems, novels, videogame dialogue, academic articles, or religious texts. To help me flesh out the process of translating religious texts in particular, I had the pleasure of speaking with Lloyd Peckham, lovingly referred to as “Uncle Lloyd” by his students and friends. With a background in translation that has spanned decades, Lloyd lived on the island of New Guinea and raised his children there while working and training in the field of biblical translation. It was a joy to interview Lloyd in person, which is a rarity nowadays. Even though he is recently retired, he continues to value and work towards training translators across the globe. Below is our conversation.

Could you tell me a bit about your background in translation?

LP: I think I was born into translation, but didn’t know it. My mother was very linguistically inclined, since she grew up in Brazil speaking Portuguese, French, Spanish, and English. Additionally, translation was the profession of many of my ancestors. My grandfather did it for farmers in Brazil, developing a breed of cattle that could withstand the rigors of the climate. My great-great grandfather traveled by covered wagon in the 1850s, intending to help draft translations for Native American communities. However, when he arrived to find others already doing that, he served the settlers in Oregon instead. Even going back all the way to my 16th and 17th century ancestors, who were French Huguenots, it is clear that I come from a long line of translators.

I wasn’t aware of this lineage in my youth. However, when I was only 7 years old, I knew that I wanted to travel the world and bring knowledge of God’s love to other countries. From then on, I always asked my teachers for extra homework. My friends thought I was crazy, but I knew I’d need the extra knowledge for wherever I ended up going in the world. I wasn’t sure where I would end up, but I figured I’d better know about everything. I wanted to know about every country, every people group, and every culture, so when I went to college I majored in anthropology and minored in geography. While I think that my role in translation was inherited, I brought that potential to fruition with intentionality.

Could you tell me about your experiences in grad school?

LP: I studied linguistics at the University of Washington and at the University of Texas in Arlington. At that point, I had already spent a couple summers learning an Aztec dialect down in Mexico. So, it only felt natural for me to finish out my Master’s degree by using Huasteca Nahuatl, one of the major Aztec dialects, as my required non Indo-European language.

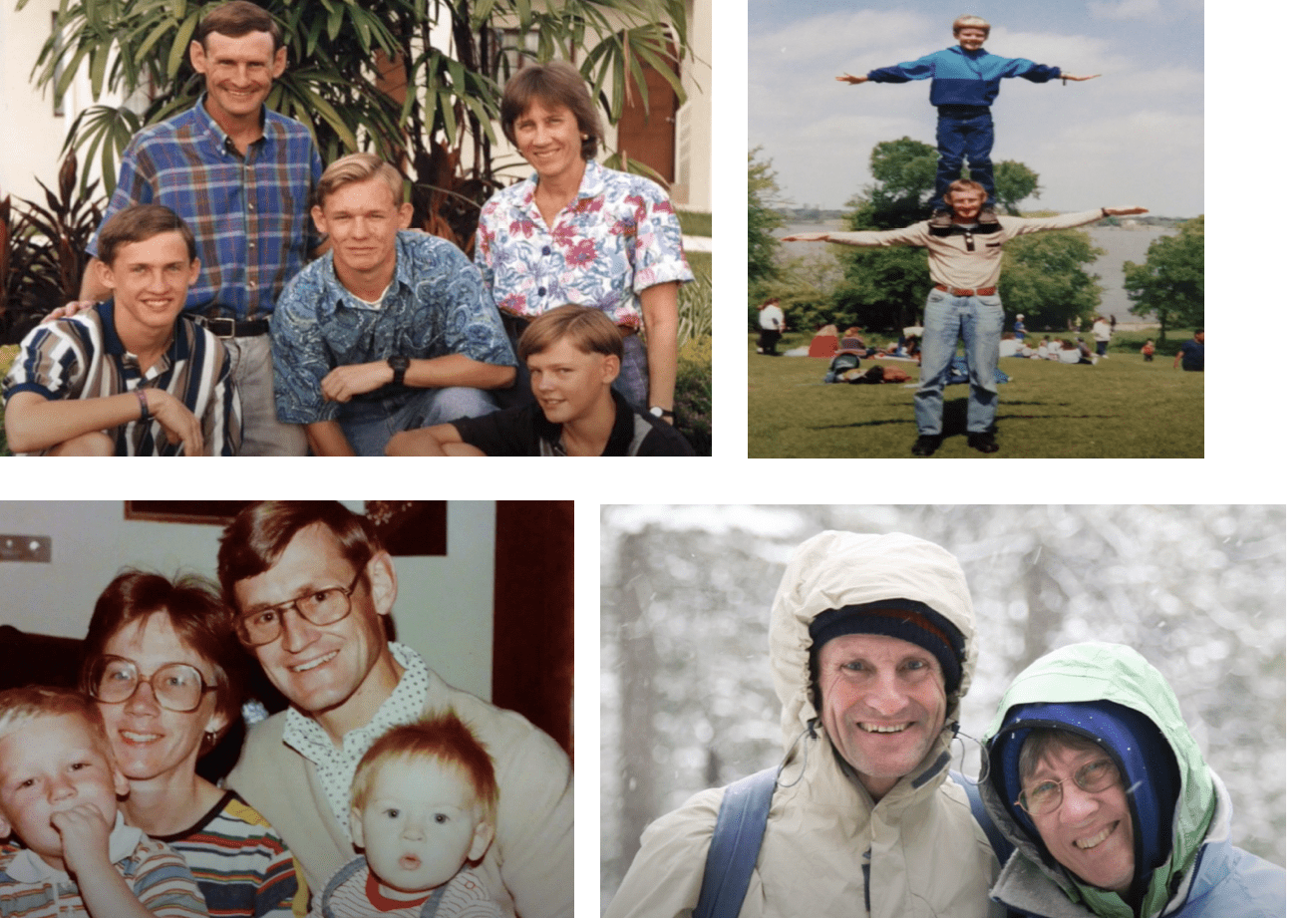

Nancy, the woman I met in college and married, was trained as a nurse. The world of linguistics was new to her, but she ended up taking Greek and other general linguistics courses, and was able to then apply both experiences to her work. However, when she traveled with me as I worked on finishing my M.A., she was inhibited by language. I had lived in South America when I was 14, 15, and then 17 years old, and I had worked as an interpreter on trips to Ecuador, Peru, and Mexico. I was ahead of her in Spanish, the national language, and in Huasteca Nahuatl, one of the local languages. Whenever I spoke either language, she would begin to withdraw. And that’s when I prayed, “Lord, you’ve put us together. Please send us somewhere where we can be equally ignorant.”

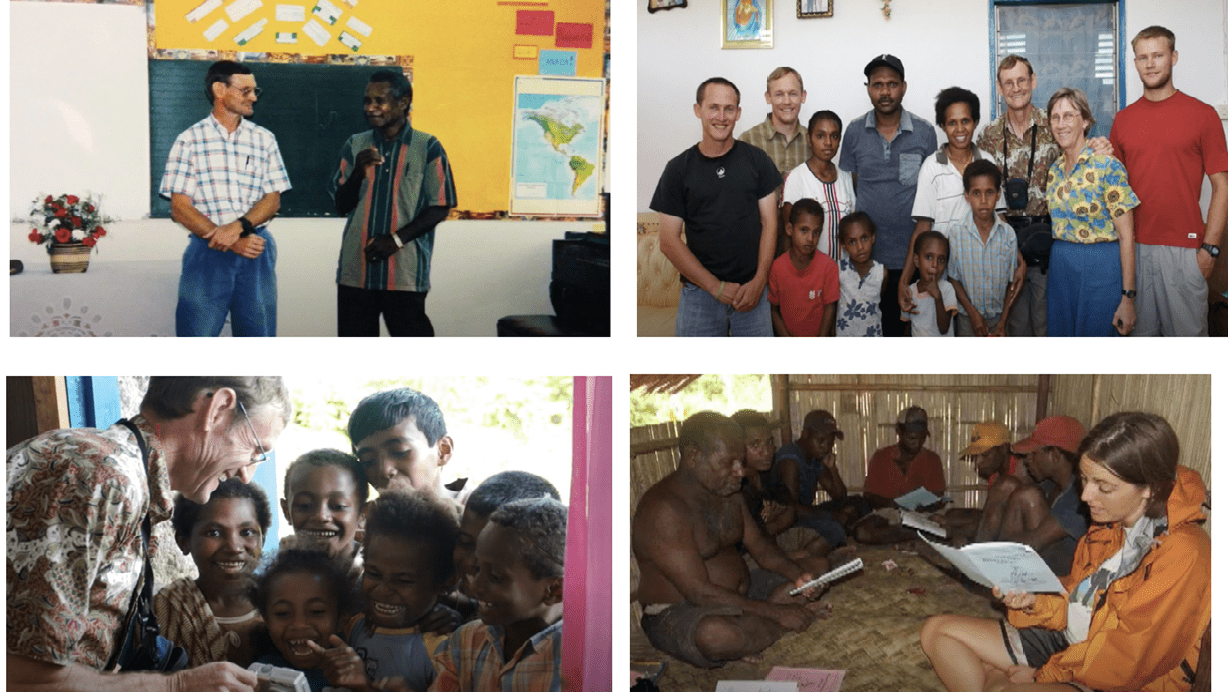

That was the summer of ’76, when Indonesia’s doors first began to open to linguists. Since I was just finishing my Master’s degree, I knew I’d be able to teach in Indonesia through the university and do linguistic research on unknown languages on the side. So, we went where neither of us knew a thing, and we learned Indonesian together. After my wife and I had studied the national language, we decided to go out and learn a local, unwritten language on the island of New Guinea: Mairasi. We then trained some of the locals there to be translators, that way when we were gone, they could continue without us.

But then, as I was in the process of training the local translators, I sampled all the regional diseases. I got very sick with malaria, and had a toxic psychosis reaction to the malaria medicine. I then got elephantiasis, which I had for the next 18 years. I was told to leave the country and never come back, and it forced me to detach from the village I’d lived in, poured into, and raised my kids in for the past 13 years. It was a very teary departure at the airport, but the locals told me, “We’re not going to quit.” So they kept making rough drafts of translations and sending them to me, whether I was in California or Texas or Singapore or the Philippines. I was able to train and translate in six other Indonesian languages, but was not allowed to go back to the island of New Guinea.

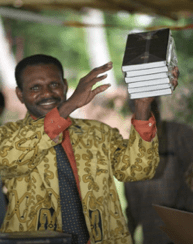

The Mairasi people eventually translated the entire New Testament with my distant supervision, and I was so proud of those who had taken the helm. When it came time for the dedication of their New Testament translation, it was arranged for me, my wife, and my kids to be there at one of the villages for the dedication and distribution of the books. We are grateful we were able to multiply by training other people in translation, some of whom are now certified international translation consultants. Our love and knowledge of translation ended up going from me and my family to future generations and their generations, and that is such a blessing to me.

So, it sounds like you started paving a road, but then because you trained people, that road has now split and stemmed off into multiple directions. The outcome is more than you ever would’ve been able to do on your own.

LP: Exactly. And it is so satisfying to see that. Some of the translators that Nancy and I trained have now gone on to train their own children. So, although Nancy and I may not be able to go back to Indonesia, the work of translation for those 700 Indonesian languages goes on in our absence.

Right. In life, I’ve learned that the mark of a good leader is that, when you’re gone, the people you’ve trained can take your place. It sounds like you’ve done just that. And the people you’ve trained will train the next generation, and the next generation will train the following generation, and so on, ad infinitum.

LP: You have caught the key principle. It reminds me of my son. Nancy and I raised three boys, three years apart, starting three years after we got married. All were born on the island of New Guinea, where we were doing Mairasi translations. And the young one decided, after three Bachelor’s degrees in several different disciplines, to be a doctor. So, after obtaining the necessary education, he began applying for residencies. People told him to apply to three or four of them, but he ended up getting invited to around twenty of them and had to turn down others. You know why? When they interviewed him, he’d tell them, “I don’t want to be a doctor. I want to be a trainer of trainer of trainers of doctors in countries that have inadequate healthcare systems.” For example, in both Africa and America, he is currently teaching doctors how to operate an early model of miniaturized ultrasounds at bedside, since they are cheaper to buy, easier to transport, and quicker to use. Likewise, I trained to be a linguist and a translator, but instead I trained the local people. Sometimes they only had third grade education, and sometimes they had a college education. Either way, I trained them to be the translators, that way when I was gone they could continue without me.

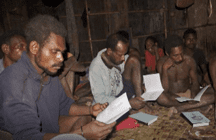

You cannot let your pride stifle the people you train—let them be better than you. Don’t ever underestimate anyone. Bring them to the top of their potential. I didn’t go to Indonesia as a translator, I went as a trainer of translators. For example, when I was learning more about the Mairasi language, there was one villager, Benny, whom I was training as an anthropologist. He didn’t have any higher than a third grade education, but I sent him around with a tape recorder to record the community’s folklore, since all the key terms of anything about the spirit world came from these folktales. I wanted to base my knowledge of the Mairasi language on their vast oral literature. So, for two years or so, Benny went around recording, and he would transcribe and sometimes even translate some of their stories into Indonesian.

He always wanted to learn, and wanted to get more involved with the translations I was doing. At one point, Benny said: “I’d sure like to help translate God’s book into our own language.” I had an open office policy, and I had a chart on the wall telling which books of the Bible there were, and how many chapters were in each one. So, I helped him practice. He decided to pick two small ones to start with: Jude and 2 Peter. As I would check his translation drafts, he’d notice that I was looking at another book, separate from the Indonesian texts. When he asked me what it was, I told him that it was Greek, a language that many figures in the New Testament spoke. And Benny said to me, “Well, teach me that too, then.” And right then, I remembered: Don’t underestimate anyone, bring them to the maximum of their potential. So I started teaching Benny Greek, starting with the alphabet, then key words, then key phrases, and Benny just kept going and going and going.

Benny sounds resilient. With all of your experiences, could you tell me a little bit about the importance of word choice in translation?

LP: Yes, word choice is so important. Let me tell you a story. A committee was checking the Mairasi book of Mark. The doors and windows of the room were opened, and the people in the community who weren’t involved in the translation came and gathered around, sitting on the dirt or on benches, because they wanted to hear the whole gospel of Mark read in their language. So the committee read through the whole book of Mark, and they came to the word for “cross,” which was “salib,” a borrowed word from Indonesian. However, an inlander, an uneducated man named Reuben, said in Mairasi, “Salib? That is not our word. Isn’t that from the Malay language? Shouldn’t the word just be what we call our chest-measurement wood?” And the committee started thinking about it.

When a Mairasi man dies, an old, broken canoe gets fashioned into a coffin. The men work at shaping a coffin out of a canoe, while the women take the body, wash it, perfume it, and wrap it in new cloth. But the men have no access to the body to measure it, since the women are washing it. So, before they give the body to the women for washing, they get two pieces of stiff reed, measure the deceased’s shoulder width and his height, and then they tie the two measured reeds together in the middle, forming a cross. This is called “chest-measurement wood,” and it is a very common aspect of the Mairasi vocabulary. Reuben was saying to these learned scholars, “Why are you using a foreign word when we could use our own?” And they started to realize it, so they started listening better to the inlanders, and even began taking dialectal differences into account.

After that point, they made sure to cater the text to the people who would have less access to it, both in vocabulary and in pronunciation. But who would’ve thought about the Mairasi word for “cross” if they hadn’t actually listened to the dialect of the people? The people are hungry for knowledge, and they really want to learn, but they’re having to jump over the hurdle of foreign words, which isn’t fair.

Loan words from other languages get messy, because they rarely keep their original meaning. This is usually because, instead of being translated, the words get transliterated, resulting in the word taking on different meaning and significance from culture to culture. This leaves room for a lot of error.

Especially with words that become imbued with religious meaning, it seems important to stay true to the words’ original meanings, since a mistake could carry consequences of misinterpretation in a community that spans for generations. All in all, the translation of religious texts sounds like a dangerous game of telephone.

LP: Exactly. And mistakes have been so often made in non-religious contexts as well, often in French, Latin, or German—when a word gets assimilated into a new culture and is used again and again with its new meaning, its original meaning gets eclipsed. The words take on a different life. Very few cognates (borrowed words) ever truly stay with their original meaning. So, that’s why in my own work and training I steer very clear from transliteration. Whether it be in Islam, Hinduism, or Christianity, so many religious words have been transliterated, like karma, jihad, and baptism. These words all had good, consistent meaning in their original contexts, but as the words got borrowed phonologically rather than semantically, we reinfused meaning into them.

That’s very true. Based on your own personal experiences, what have you found is the importance of fully immersing oneself in the culture that the translation is being created

LP: I love this question. I think you got some insight from my previous example of chest-measurement wood. How would I have known about that personally if I hadn’t been through many Mairasi funerals? I wouldn’t know the little cultural things that make the language special, nor would I have been able to coach the translators beyond a very wooden, literal version from Indonesian if I hadn’t immersed myself and become a part of their community. I was given a name by them, and my kids were adopted into their language and culture.

Could you tell me a little bit about what being given a name means in the Mairasi culture?

LP: Yes, it is such a big a big part of their culture. They are a tuber-based culture, which means that they eat sweet potatoes, taro, and other foods that grow underground. And their word for truth is the same as their word for tuber, because I could look at a garden full of sweet potato leaves and think, “This is a nice garden!” But if I don’t dig in there and actually pull out sweet potatoes, then my assumptions are of no use. Same with people. The whole concept of your name in the Mairasi culture is the essence of who you are. Name is existentially intertwined with your totality of being, so to not have a name is to not exist. When we came ashore for the very first time with our firstborn son, Daniel, just about two months old at the time, my wife and I were seasick. The captain of the boat was at the time holding our little blond son up in the air for all the villagers to see. And out from the crowd runs Philippe, past the shore and through the coral. He grabs our son from the captain’s hands, holds him up in the air, and then gives him a name: Janggauru. Everyone then passed him from one person to the next, celebrating that his core, his essence, was Janggauru, which means “the fertile farmland at the mouth of the one and only river.” They had had an old man named Janggauru who had died, and, to keep his essence and his memory alive, they gave his name to our son.

That sounds like a high honor.

LP: It really was. And I am “Janggaur nambae nani,” which means “Janggauru’s daddy.” And my wife is “Janggauru’s mother.” That is how they would always refer to us. They don’t use these other labels, like Lloyd or Nancy or Daniel. There is a multi-faceted naming system within the Mairasi culture. People will have four or five names, and many are earned by their character qualities. So, besides being Janggauru’s daddy, I did accidentally overhear some people, after I’d been there for a while, referring to me with a second name. It was a name that had come up in one of the most sacred folktales, named after the hard core of the ironwood tree: “Sanggere.” It literally means “hard core,” in the sense of resilience.

That’s very interesting—I’ve never heard of people having multiple names. Also, congratulations on retiring, that is a big milestone! Looking back, what lessons have you taken away?

LP: I think that, in the process of helping others learn how to translate and replace me, I became the translation, not just the translator. What I mean is, I became a reflection of God’s love through the work I did. That’s my goal in those I train. If you cannot tell that God is love from my life, then I have failed. However, if you go into translation, there is one thing you need to be mindful of—you need to be aware of how neglected your kids may feel. I knew about this danger going into the field, so I was very intentional about holding my sons and my wife up as far more important than any work I got done. They’ve always known that they were my priority, and that some lofty goal of publication would never get between us.

Right. I think that we grow as people when we see a way that things have always been done poorly in the past. We notice it, we recognize that we have the potential to go down that same road, and then we change the pattern of how things are done.

LP: Exactly. That has been a con I’ve seen for translators. Same with missionary kids. But I thank the Lord that my boys have become translations as well. Being a translation has been my life and shaped my life, and even if I’m retired, I can still build translations within other people.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October / November 2021 Issue: Read Global.