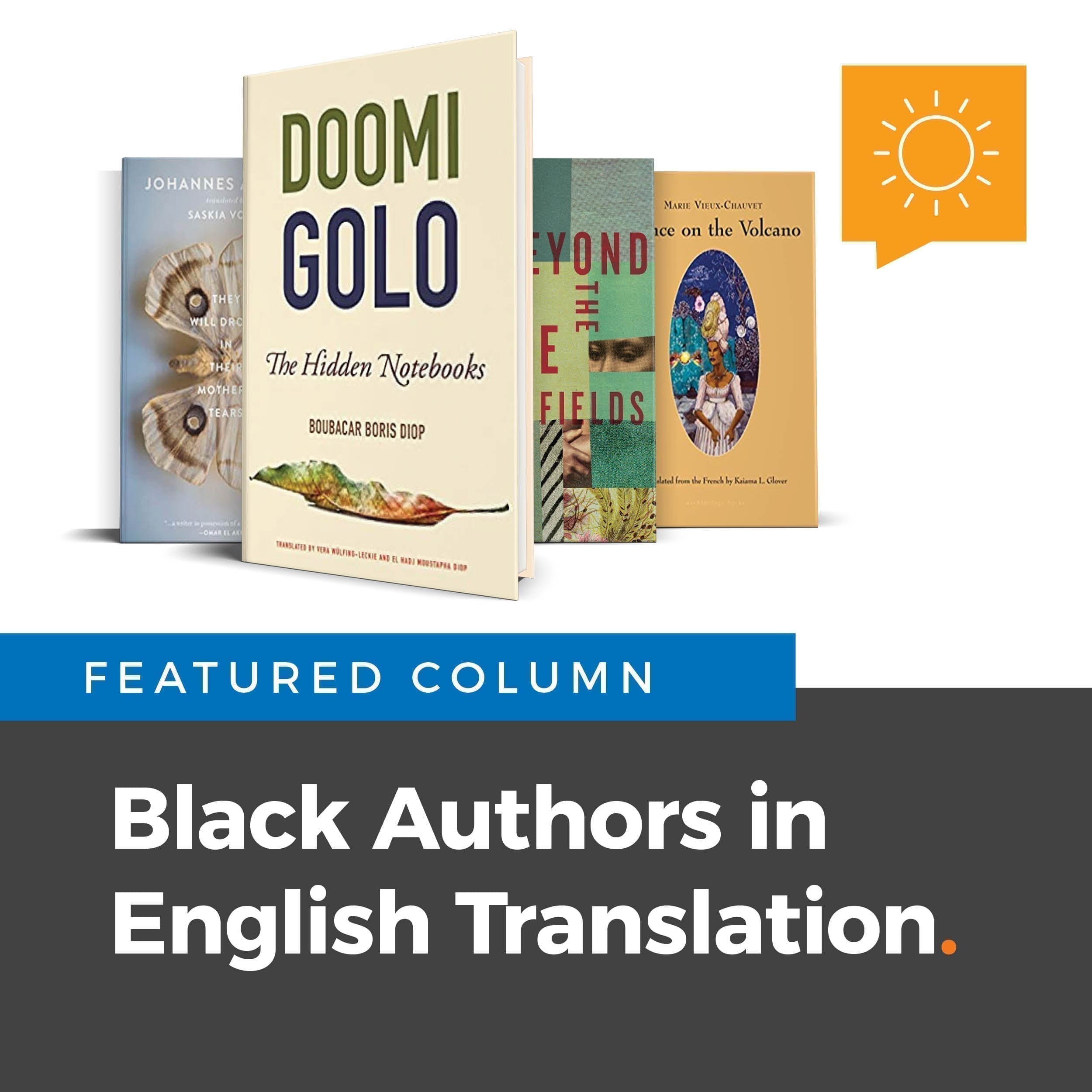

Black Authors in English Translation

Vera Wülfing-Lecke

Doomi Golo—The Hidden Notebooks

Author: Boubacar Boris Diop

Publisher: Michigan State University Press (2016)

Country/language: Senegal/French

Allison M. Charette

Beyond the Rice Fields

Author: Naivoharisoa Patrick Ramamonjisoa

Publisher: Restless Books (2017)

Country/language: Madagascar/French

Saskia Vogel

They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears

Author: Johannes Anyuru

Publisher: Two Lines Press (2019)

Country/language: Sweden/Swedish

Kaiama L. Glover

Dance on the Volcano

Author: Marie Vieux-Chauvet

Publisher: Archipelago Books (2017)

Country/language: Haiti/French

These works of fiction, written by black authors in their native language and translated into English, take great care to be true to their country’s culture and history. Doomi Golo—The Hidden Notebooks is a story of pure imagination, but the author also uses it as a platform to help certain tragedies be remembered so as not to be repeated. The other three books are historical fiction. But despite the fact that the painful events revealed in these pages happened decades or in some cases centuries ago, you will notice a very familiar ring as we continue to deal with many of the same issues today, such as racism, war, inequality, and white privilege. These books not only deliver great writing, but they also will make you question how far humanity has, or has not, come. We spoke with the translators of these four books to learn more about the relevance of their authors’ works in today’s society.

These works of fiction, written by black authors in their native language and translated into English, take great care to be true to their country’s culture and history. Doomi Golo—The Hidden Notebooks is a story of pure imagination, but the author also uses it as a platform to help certain tragedies be remembered so as not to be repeated. The other three books are historical fiction. But despite the fact that the painful events revealed in these pages happened decades or in some cases centuries ago, you will notice a very familiar ring as we continue to deal with many of the same issues today, such as racism, war, inequality, and white privilege. These books not only deliver great writing, but they also will make you question how far humanity has, or has not, come. We spoke with the translators of these four books to learn more about the relevance of their authors’ works in today’s society.

HOW DOES THIS WORK OF FICTION RELATE TO ACTUAL HISTORY?

VWL: Within its multi-layered, nonlinear framework, the narrator either simply touches upon, or gives an in-depth account of both local and more far-flung events, such as the battle pitting the Damel (king) of Cayor (one of the old kingdoms of Senegal), against his own son, or the day in March 1821 when the Women of Ndeer set themselves alight in a straw hut in a desperate bid to escape slavery. The Joola Ferry Disaster and the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961 are mentioned, as well as ‘The great National Throat Slitting’, a sarcastic allusion to the Rwandan Genocide, among other historic events.

AMC: The political and social monarchy, and the major historical events, are happening in the background, but they’re all true. Players such as the first king and queen of what was essentially Madagascar are real, as is French industrialist Jean Laborde. Everything he does in the book is real and built by him. It is not the focus, but it’s how those types of things affected normal people.

SV: This book relates heavily to present-day. For example, on August 19th, the Muslim Advocates organization reported that U.S. Customs and Immigration in Miami were feeding pork to detained Muslims ever since the outbreak of COVID-19. It’s practically taken straight from Anyuru’s novel. With the current U.S. administration and the legacy of 9/11, this book has a good chance of striking a nerve.

KLG: This book is set in a momentous time in Haitan history leading up to the Haitian revolution and the war with France. There is a massive conflict between the black enslaved population and mixed-race people who are not enslaved but do not have the same freedoms as white colonists. The book deals with this powder keg of history and gives the perspective of all three groups.

WAS THERE A SCENE IN THE BOOK THAT MOVED YOU MORE THAN ANY OTHER?

VWL: The metamorphosis of Nguirane Faye’s dark-skinned daughter-in-law, Yacine Ndiaye, into a white woman named Marie-Gabrielle von Bolkowsky is a stand-out passage. Yacine personifies the reluctance of many of the author’s compatriots to accept and embrace their own identity as black Africans. To achieve her ultimate goal of becoming white, Yacine is prepared to comply with all that witch doctor Sinkoun Tiguidé Camara demands. What she doesn’t anticipate is that such miraculous gifts usually come at a price.

AMC: Fara’s mother is forced to undergo a trial of poison called tangena. These trials really happened to thousands of people in Madagascar. If you were able to physically expel the poison and survive it, then you were considered innocent. If you died, then you were considered guilty. The story tells of the horrific physical things she’s forced to undergo and the mental anguish of the entire community turning on her, all told through the perspective of her daughter who is watching this unfold in real time.

KLG: At age 15, Mynette is put on stage for her debut performance. She has no familiarity with white society and all she sees is a sea of white faces. She’s terrified and suffers incredible paralysis. Then she looks up and sees the black section of the hall and her family is there. And she remembers how her people are moving toward liberation and competency and she’s able to sing for them, bringing the house down. She realizes her voice is a political gift and she overcomes her fear. It’s a very moving moment.

WHAT LESSON CAN WE LEARN THAT MIGHT HELP US OVERCOME ONE OR MORE OF TODAY’S CHALLENGES?

VWL: In the advice Nguirane Faye passes on to Badou in Notebook 5, he explains, in his cryptic way, that we need roots before we can attempt to fly, and that before venturing outside our comfort zone, we should first get to know who we are and where we come from. In an era of seemingly relentless progress and information overload, we must learn that not everything that’s new deserves to be adopted, while traditional methods that have stood the test of time are ruthlessly discarded

AMC: There is a racial tension in Madagascar that parallels racism everywhere. But it is not between black and white. There are 18 different tribes and the distinctions and racial tensions between the lighter-skinned Malagasys, who have smoother hair, and the darker-skinned Malagasys, who have crimped hair, continue to this day. I was not expecting that.

SV: Remember to care for our fellow humans, and that no matter how different we may seem, we are all human, we all belong here, and we owe it to ourselves to find a way to make life as good as possible for all, not just a few.

KLG: Sometimes the best way of affecting radical change is through networks, and they can be incredibly diverse. It’s a reminder that history is often a lot messier and alliances and solidarity can exist beyond gender, race or class.

[cm_page_title title=”Continue Reading” subtitle=” Shelf Unbound”]

Article originally Published in the October/November 2020 Issue: Read Global.