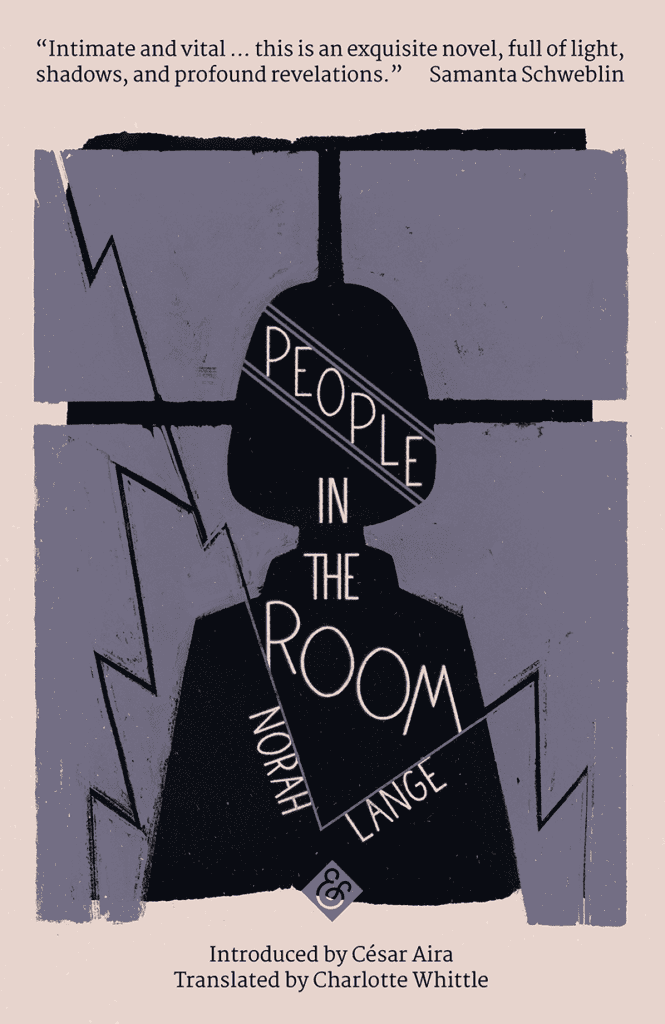

People in the Room

By Norah Lange, Charlotte Whittle (Translator)

A young woman in Buenos Aires spies three women in the house across the street from her family’s home. Intrigued, she begins to watch them. She imagines them as accomplices to an unknown crime, as troubled spinsters contemplating suicide, or as players in an affair with dark and mysterious consequences.

Lange’s imaginative excesses and almost hallucinatory images make this uncanny exploration of desire, domestic space, voyeurism and female isolation a twentieth century masterpiece. Too long viewed as Borges’s muse, Lange is today recognized in the Spanish-speaking world as a great writer and is here translated into English for the first time, to be read alongside Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector and Marguerite Duras.

About The Author: Norah Lange

Norah Lange was an Argentine author, associated with the Buenos Aires avant garde of the 1920s and 1930s. A member of the Florida group, which also included figures such as Oliverio Girondo and Jorge Luis Borges, she published in the “ultraist” magazines Prisma, Proa, and Martín Fierro

Read an Excerpt

Despite their excuses, I tried many times to convince them of how easy and convenient it would be for them to communicate, and even call for help, if they had a telephone.

“The afternoon I saw you at the post office, it was reassuring to know I could call home and ask someone to come and get me. What if one of you happened to be alone one night, and needed something? . . . You need only call me, or call someone else…”

“None of us is ever alone,” they would answer, but when I noticed the second showing enough interest to persuade the others, I persisted. Except for the lack of calls, and perhaps its dubious usefulness since few families in that part of Belgrano had a telephone, I hardly suspected the reason behind their resistance and misgivings. Since no one ever visited them, the chances of anyone calling were so slim that perhaps they preferred to shield themselves from this new way of being forgotten. Someone might, on seeing their names in the directory, discard what was left of an old memory, and return, puzzled, to the habit of forgetting them.

I knew my efforts came only from wanting to telephone them myself, to get closer to them, to force them to be precise and at least say who they were; but so as to hide my intentions, I offered my own experience, explained how for us the telephone had been a novelty, and described how keenly we’d tried to guess at the owner of the still-courteous voice uttering the words in a careful tone, as if fearing, as it passed through houses, courtyards, and side streets, that a stranger might listen in on what it didn’t quite dare say. I also told them that at first the telephone was so entertaining that one of us would call our house from a local store, to make sure the crucial voice was still in its place at the other end of the line, traversing wires, accepting its movement through the air, grazing the treetops, saying, “Who is it?” It was almost like opening a letter, except the voice would disappear, and afterward one was left with the pleasure of the voice and the way it changed.

Perhaps my eagerness made her reflect on remembered streets, where her first call might ring out, and return her to familiar places, even if she only asked to be put through, and didn’t say a word. That afternoon, though, the second made up her mind, and, with a serious look, as if I were experienced in the matter and could give her advice, she asked, “Will our last name have to be in the directory?”

I don’t know why it occurred to me that I should take this chance to provoke her, to compel her, for once, to be precise.

“You could give your maiden name,” I suggested, hoping any answer she gave might bring me closer to her past, explain her stubborn, unchanging evenings.

“I can’t,” she murmured quickly. “I can’t,” she said again, as if she had to live in hiding, or hesitated to use her name, because in fact she was married, or because some burning resentment or some strange sense of shame prevented her from confessing her widowhood. The eldest turned toward her, unsurprised. I thought I’d been left with another chance in ruins, confronting another mystery I’d never be able to solve, but I didn’t dare persist. I also thought her answer couldn’t have been meant for me, since she never told me anything about her life. Unwilling to write a name on the usual applications, she seemed to me to be looking, through a half-open door, at a house she used to visit in company, since she was loved by many, sure she would return to its long table, where on Sunday nights they played cards, promising, as they said their good-byes, that there would be other such Sundays, as she felt the hand of a man on her arm for the walk home, waiting for him to open the front door, and she, later, would turn on the bedroom light, perhaps pulling aside the mosquito net from the wide bed, her eyes falling briefly on the cushions with white covers—she had always been fond of those square, slightly stiff cushions—with their halting conversations in the safe and peaceful bedroom, where she might lie awake a while longer, since she liked to hear his breath so close before turning over in the dark, and not to pray, since it was late, and she loved him, and she couldn’t pray that she loved him.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October/November 2019 Issue “Read Global”