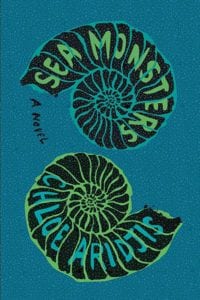

About the book:

One autumn afternoon in Mexico City, seventeen-year-old Luisa does not return home from school. Instead, she boards a bus to the Pacific coast with Tomás, a boy she barely knows. He seems to represent everything her life is lacking―recklessness, impulse, independence. Tomás may also help Luisa fulfill an unusual obsession: she wants to track down a traveling troupe of Ukrainian dwarfs. According to newspaper reports, the dwarfs recently escaped a Soviet circus touring Mexico. The imagined fates of these performers fill Luisa’s surreal dreams as she settles in a beach community in Oaxaca. Surrounded by hippies, nudists, beachcombers, and eccentric storytellers, Luisa searches for someone, anyone, who will “promise, no matter what, to remain a mystery.” It is a quest more easily envisioned than accomplished. As she wanders the shoreline and visits the local bar, Luisa begins to disappear dangerously into the lives of strangers on Zipolite, the “Beach of the Dead.”

Meanwhile, her father has set out to find his missing daughter. A mesmeric portrait of transgression and disenchantment unfolds. Sea Monsters is a brilliantly playful and supple novel about the moments and mysteries that shape us.

Read An Excerpt:

Featured In June/July 2019 Issue: Summer Reads

“Imprisoned on this island, I would say, imprisoned on this island. And yet I was no prisoner and this was no island.

During the day I’d roam the shore, aimlessly, purposefully, and in search of digressions. The dogs. A hut. Boulders. Nude tourists. Scantily clad ones. Palm trees. Palapas. Sand sifting umber and adrenaline. The waves’ upward grasp. A boat in the distance, its throat flashing in the sun. The ancient Greeks created stories out of a simple juxtaposition of natural features, my father once told me, investing rocks and caves with meaning, but there in Zipolite I did not expect any myths to be born.

Zipolite. People said the name meant “Beach of the Dead,” though the reason for this was debated — was it because of the number of visitors who met their end in the treacherous currents, or because the native Zapotecs would bring their dead from afar to bury in its sands? Beach of the Dead: it had an ancient ring, ancestral, commanding both dread and respect, and after hearing about the unfortunate souls who each year got caught in the riptide I decided I would never go in beyond where I could stand. Others said Zipolite meant “Lugar de Caracoles,” place of seashells, an attractive thought since spirals are such neat arrangements of space and time, and what are beaches if not a conversation between the elements, a constant movement inward and outward. My favorite explanation, which only one person put forward, was that Zipolite was a corruption of the word zopilote, and that every night a black vulture would envelop the beach in its dark wings and feed on whatever the waves tossed up. It’s easier to reconcile yourself with sunny places if you can imagine their nocturnal counterpart. Once dusk had fallen I would head to the bar and spend hours under its thatched universe, a large palapa on the shores of the Pacific decked with stools, tables, and miniature palm trees. It was where all boats came to dock and refuel, syrup added to cocktails for maximum effect, and I’d imagine that everything was as artificial as the electric-blue drink; that the miniature palm trees grew fake after dusk, the chlorophyll struggling and the life force gone from the green, that the wooden stools had turned to laminate.”