By Alyse Mgrdichian

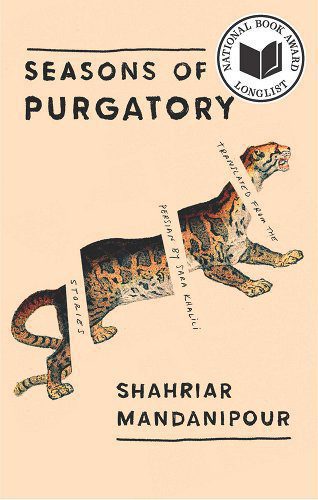

Written by Shahriar Mandanipour and translated from Persian by Sara Khalili, Seasons of Purgatory—a short story collection—has been long-listed for the 2022 National Book Awards in Translated Literature.

How exciting! I’m grateful to have received a copy from Bellevue Literary Press (the publisher), and am excited to have had the opportunity to speak with Mandanipour and Khalili personally. I feel I got to know the two of them better, and am excited to see their future collaborative endeavors—Mandanipour’s storytelling abilities, paired with Khalili’s deft translation skills, are absolute magic.

Below you can find our conversation, as well as the book’s blurb.

Synopsis: Seasons Of Purgatory

In Seasons of Purgatory, the fantastical and the visceral merge in tales of tender desire and collective violence, the boredom and brutality of war, and the clash of modern urban life and rural traditions. Mandanipour, banned from publication in his native Iran, vividly renders the individual consciousness in extremis from a variety of perspectives: young and old, man and woman, conscript and prisoner. While delivering a ferocious social critique, these stories are steeped in the poetry and stark beauty of an ancient land and culture.

Shahriar and Sara, thank you for being here! Could you tell me a bit about how you got started in your respective fields? Shahriar, why don’t you start? What has your storytelling journey looked like over the years?

SM: It was a long journey from east to west, both physically and mentally—like a Mobius strip.

After many years, I am still unsure if I am an Iranian-American or American-Iranian writer. But ‘I have a dream.’ In this New Dark Age of the world, the iron walls are growing and getting taller on our physical and mental borders. However, a Dreamland is rising in the storm: There will be a new Republic of Literature. To enter this independent arena, no visa is needed, nobody will ask about your race, religion, or beliefs, and there will be no censorship… I hope this dream comes to fruition.

I see that you’re a journalist, and have experience in war. Could you tell me about how those experiences have influenced your creative work?

SM: Being a writer or a journalist in Iran is as dangerous as fighting on the frontlines. However, your clothes and your weapons differ. Journalism brought me experience and knowledge in writing, but did not directly influence it.

And Sara, jumping over to you, how did you get started as a translator?

SK: I was a financial journalist for many years and thought about translation only when my father’s cousin, the late Karim Emami, would argue with me that I was wasting my time and I should translate literature instead. He was an editor, literary critic, and one of the most celebrated translators of English language literature into Persian. This went on until 2004 when he suggested I work with him on translating a short story for an anthology. As we translated, Karim in Tehran and me in New York, he taught me the art of translation. I was hooked. He won the argument.

Shahriar and Sara, how did the two of you meet?

SK: In 2005 I translated one of Shahriar’s short stories for an anthology of Persian literature. A year later, he called me from Brown University. He had recently come from Iran as the International Writers Program fellow for that year. He was writing a short story about censorship that was being presented at their annual festival. He asked if I would translate it. I did, and we met for the first time at the festival. The short story soon evolved into the first chapter of Censoring an Iranian Love Story.

We have always worked closely on all the translations, but more so on his two novels, Moon Brow and Censoring. Both are richly nuanced and complex in style and structure, and we worked on them in tandem. I translated as he wrote. It was difficult and certainly not the conventional way of going about it, but seeing a novel come to life in two languages at the same time was such a unique experience.

SM: Yes—Sara appeared like an angel in my literary life. She is fluent in three languages, talented in understanding the structure of language, familiar with the world’s literary masterpieces, and, most importantly, creative … and at the end of the day, Sara loves literature and cares about injured Persian literature. She also has translations from other Iranian writers and poets, including a great Iranian modern woman poet, Forough Farokhzad.

As Sara said, in 2006 Knopf editorial offered us an excellent contract for Censoring an Iranian Love Story, based on only 80 pages of the novel we had in hand at that time. We had hours and hours of daily conversations about the shadowy words and syntaxes of our two uncommon languages. Those times were helpful, and as a result I better understood her creative English prose, and she got closer to my personal Farsi. With enthusiasm, we continue the work.

Shahriar, what was the process of compiling this collection like for you? What themes and ideologies did you seek to highlight through your work?

SM: For years, while I was working on a new novel, Sara Khalili translated those stories. Some of them had been published here and there, like in The Kenyon Review, The Literary Review, Agni, or The PEN Anthology of Contemporary Iranian Literature. Sara’s translations of those stories won the PEN Award.

I don’t believe in any ideology or engagement in writing, just commitment to the aesthetics of the art of fiction. But I am sure if we were faithful to the human beauties of art, other human ideals and aims would be planted in the layers of our work.

Sara, what was the process of translating seasons of purgatory like for you?

SK: We worked on translating the short stories over a few years. The voice, tone, and manner of speech of each story’s narrator is different, as is the rhythm and style Shahriar has used. Capturing and mirroring them in English was the most challenging part of the work.

When deciding which projects to pick up for translation, are there any themes or patterns that you find yourself more interested in?

SK: For me translation is a quiet, intimate relationship with a book. I need to truly like and appreciate the one I choose to live with for months or years. Beyond this, I look for a literary value and cultural worth in the book that I believe deserves a wider readership and the time I would need to dedicate to it.

And Shahriar, your descriptions are enchanting. Could you tell me a bit about how you use your observational skills to create such vivid, everyday details?

SM: There is no angel of inspiration, no mountain or cave for illuminating. Reading and writing are vital daily jobs. Moreover, I have accustomed myself to realizing the world as a great fiction masterpiece. In other words, I gaze at the world; presumably, it is in working fiction, and I am a character in this novel as well. According to this approach, every event could potentially be the subject of tens of stories; every person has a personality and persona to transfer to fiction, and the setting could be anywhere at any time. But, alas! My life is too short to write all of those stories.

I start with the de-familiarization of my words and the deconstruction of my old syntaxes. There are times that I also feel bored with my previous prose. I also like the synesthesia technique to create a dialogue between things, feelings, and words. If we could be a master of this method, the result of the synesthesia approach would be infinite.

I don’t start with ‘Once upon a time there was…’ to write a linear story. Most often, it’s ‘There is nothing new under the sun.’ But each subject has tens of possibilities for narrative form. In my fiction writing workshops, I teach that writing is somehow making connections between things that are not connected in reality. Literature is inventing relationships between phenomena and creating the desire of connection among meaningless things.

Sara, of all the books, stories, and poetry you’ve translated, are there any projects that you’re more fond of than others? If so which ones and why?

SK: There are two books that are very dear to me. Shahriar’s Censoring an Iranian Love Story, because it is brilliantly conceived and beautifully written and it’s the first novel I ever translated. I also adore In the Meadow of Fantasies, an exquisite children’s book recently released by Archipelago Books. Nooshin Safakhoo’s illustrations are stunning and Hadi Mohammadi’s story is enchanting.

And Shahriar, what are you currently reading? What are your favorite stories, and why?

SM: I am holding three online workshops on literature, and I teach story writing techniques and forms using the world’s greatest short stories and novels (not necessarily average famous stories). The workshops are a chance to reread those stories with new eyes. I can explore why and how those works are always on readers’ horizons.

For the second part of your question, I must give some advice: never ask writers about their favorite writers or who has affected their work because they will likely give you the wrong address or reply with a story instead.

Fair enough! Shahriar and Sara, this next question is for both of you. Are there any forthcoming projects that we can look forward to seeing from you (that you’re willing to talk about)?

SM: There is always a new novel for writing, but I must not talk about it as a personal rule. As a result, you will lose the enthusiasm for writing challenges and miss the sense of the mysterious and unknown possibilities of an unborn story…

Well, whatever mysterious project you end up writing next, I look forward to reading it. And Sara? How about you?

SK: I just finished translating Tali Girls, a novel by the Afghan writer Siamak Herawi that Archipelago is publishing. And now I’m going to take a break.

A well-deserved break, I’m sure. Thank you both for your time!

About the Authors

Shahriar Mandanipour is an award-winning, exiled Iranian author and journalist who served in the Iran-Iraq war. His fiction has been published throughout the world, including two acclaimed novels published in English (Moon Brow and Censoring an Iranian Love Story). In 2006, Mandanipour moved to the United States. He has held fellowships at Brown University, Harvard University, and Boston College, and has taught at Brown University and Tufts University. He lives in California.

Sara Khalili is the recipient of a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Award for her translation of Seasons of Purgatory. She lives in New York, working as an editor and translator of contemporary Iranian literature and poetry.