By Christina Consolino

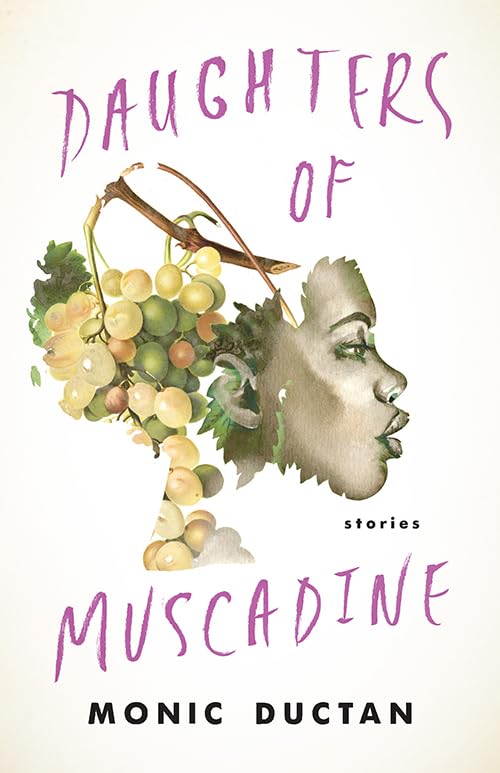

Author Monic Ductan’s debut short story collection, Daughters of Muscadine, was named A Book All Georgians Should Read for 2024 by Georgia Center for the Book, and it won the 2023 Weatherford Award. Some characters in the collection make repeat appearances, but at the heart of the book is the setting—Muscadine, Georgia. Monic shared with me a little about how the book, which explores the struggles and triumphs of a group of women in the South, came to be.

Your debut, Daughters of Muscadine, is “a loosely linked collection of stories.” Did you set out to write a story collection, or did you have a standard longform novel in mind? During the writing process, did you ever second-guess yourself?

MD: I write in a few different genres. I’ve been writing essays, stories, poems, and a novel since I started graduate school in 2012. I finished this book of stories first because I was made to write short pieces for my fiction workshops in school. I wrote half the book as a student in my MFA and my PhD programs, and then I wrote several additional stories after I started teaching full-time. Finally, I had enough stories for a book. I had an excellent editor at Kentucky Press who asked what I could do to the stories to make them more cohesive, so I decided to set them all in Georgia, mostly in the town of Muscadine, Georgia. Yes, I definitely second-guessed myself. I think self-doubt is pretty common among writers and artists, especially when we receive a lot of rejection and criticism. I started out by publishing in literary magazines, and everyone knows how selective magazines are. I learned to take rejection by receiving hundreds of form rejection letters from journals. Still, even when you’re used to rejection it often stings something awful.

In an interview with Nancy Christie, you said, “I wanted [the book] to feel like life in a small town where everyone knows each other and is connected in some way.” You succeeded! From the first page, I felt like I was just walking into the lives of the characters. How easy or difficult was it to bring that feeling to the page, and how did you do it?

MD: Thank you! I’m a very slow writer, and the stories developed over a period of years. A lot of writing is rewriting, just returning to the manuscript again and again until you’re satisfied with it. I always tell students that I rely on my beta readers, too. If something isn’t clicking, my betas let me know, and they give good advice for how I could potentially fix it. You can’t please every reader, but you can choose a certain type of ideal reader, and then write to please that ideal person. None of my stories look anything like their original drafts. I kept asking myself what I could do to complicate each story, basically by asking myself, “What would happen if she did this?” or “What if this person doesn’t react the way they’re expected to?”

I spent all of my growing up years in northeast Georgia. Lots of people have asked how I brought the setting of my book to life. It’s easier for me to write about a familiar place. Some of the places in the book are based on real-life places I know in Georgia. If I can see a place in my mind’s eye, then it’s easier for me to put it on the page. I also think that creating a setting involves paying attention to the smallest of details, such as the way the hills slant or the way a dog lifts its head and thumps its tail on someone’s porch.

Author Crystal Wilkinson wrote of the book, “The smart and observant girls and women in this linked collection are magnificently portrayed by a writer with a sure hand for the nuances of place, race, and belonging.” Did you have anyone particular in mind when you crafted these girls and women? Why is it important to you to portray smart females in your writing?

MD: I have a certain type of reader in mind. I write for people who read the same sort of fiction that I read. We like stories about everyday people that have a compelling conflict, the sort of conflict that makes us ask, “What would I do in a similar situation?” I think I write about smart females because those are mostly the types of books I read. Recently, I read two books by Amy Engel, and I like her style and subject matter. I also like Billie Letts. My favorite classic stories that I return to again and again are Bastard out of Carolina and Streetcar Named Desire. When I was a child I read and re-read The Logan Family series by Mildred D. Taylor and Up a Road Slowly by Irene Hunt and Jacob Have I Loved by Katherine Paterson. I also read quite a bit of memoir now, and some of my favorite books to teach from that genre are Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls. All of these aforementioned books have strong women at their center. Even my favorite films are often about women who struggle to overcome some obstacle. Those are inspiring stories to me, even when they don’t always have happy endings.

In reference to that same quote by Wilkinson, what made you want to write about “place, race, and belonging?”

MD: My mama has a black and white photo of my great-grandma, Eula Knox White, who was born in Georgia in the 1800s. Eula’s parents and grandparents were also Georgians, according to my mama. This means that my maternal family has been in Georgia for at least five generations before me. That shows the extent of my connection to that place. When I’m writing, I often imagine places from my childhood, like the small house where my grandparents lived with their ten children near Commerce, Georgia, or the fields and woods surrounding the trailer I grew up in. People ask why I’m a Southern writer. The answer is that I never really thought much about being any other type of writer. It’s in the blood, I guess.

In terms of belonging, I have never felt like I fit in most spaces, which could explain why I write about estrangement. The part of Appalachia that I’m from is very white. It’s changing now, like most places, but my town was probably 85% white when I was a child. I was often the only Black child in my classes at Maysville Elementary, and I was sometimes one of maybe two or three other Black teenagers in my classes at Jackson County High. Race wasn’t the only thing that made me feel different, though. My family was also really poor, a fact I was ashamed of and tried hard to hide. It wasn’t until I got to graduate school that I was diagnosed with ADD and started to figure out that I might be on the autism spectrum, which could also explain why I have often isolated myself from others. I worry about being judged for not always getting the joke or for saying something awkward.

You once said that you like to read “everyday” stories (I do too!). Why? What do you find so meaningful in those stories, and why did you decide to write a book of everyday stories?

MD: I’m most intrigued by realistic stories about things that could (and do!) actually happen. These stories allow me to settle into their worlds so easily. The familiarity in those stories is comforting to me.

How do you, as a writer, find the right balance so that heavy themes like estrangement and race relations don’t weigh the reader down?

MD: Good question. I was talking about my book at a college recently, and someone said they gave the book to a professor on campus who read it and said it was surprisingly dark. I don’t think I write dark stories on purpose, and obviously not every story in the collection is dark. I try to find a balance between different topics and tones so that the collection is not just all misery. There are a couple of happy endings in there and also some characters who get what they want.

Community and connection are themes in the book. What communities have you found connection in? Do any women in particular inspire you and your writing?

MD: I feel a sense of connection when I read Southern authors and Appalachian authors. I remember reading work by Silas House, Barbara Kingsolver, Lee Smith, Mildred D. Taylor and Adriana Trigiani for the first time and feeling like I knew and understood those people and places. The dialect(s) remind me of home. I have always been a lonely person, and some of my favorite memories involve being curled up with a book and a snack and reading for hours at a time.

I have found support in some reading and writing communities. I live in Tennessee, and my book is a Kentucky Press book, so I’ve given several author talks and readings in this region. At each event, I’ve found at least one reader that I’ve connected with. Either they came up to me to ask about one of my characters, or they told me that Muscadine reminds them of home. This makes me feel socially connected.

The book won the 2023 Weatherford Award, which honors works that “best illuminate the challenges, personalities, and unique qualities of the Appalachian South.” What does winning such an award mean to you? Does this award factor into your definition of literary success?

MD: Yes, it definitely means something to me to know that my first book won an award. I looked at the list of previous Weatherford winners, and it includes so many authors and books I’ve admired for years. I’m proud. For a long time, my definition of literary success was to publish a book with a respectable press, and now I’ve achieved that. Winning the Weatherford feels like an added bonus.

What drew you to teaching? How does teaching impact your writing and inform your work?

MD: Reading has always been a passion of mine, and teaching in the areas of literature and writing is the field most closely related to that passion. I had some great teachers in graduate school, and they inspired me and made me believe I could succeed in academia. I’m also inspired by the writing I teach. Last year, I taught some persona poems by Frank X. Walker. They were from his poetry book on Medgar Evers, Turn Me Loose, and those poems made me want to attempt to write some persona poems. I started scribbling some in my notebook using people I know or people I imagined, and hopefully something will come out of those poems one day.

what’s next for you?

MD: I get most of my writing done in summer when I’m not teaching. This summer, I’ll be trying to finish a novel about a woman named Lena (the same protagonist from my short story, “Gullah Babies”) who moves to a small town and uncovers corruption in the police department. Lena is Black and a police dispatcher, and her boyfriend is a white policeman. The boyfriend allegedly kills a Black man in Lena’s neighborhood. Lena is trying to figure out what happened the night of the shooting, and she’s also trying to figure out her relationship with her boyfriend. In addition to this novel, I also have a group of personal essays I’ve been working on for years. My poetry manuscript, Man Sold Separately, is coming together nicely, but I need another dozen poems or so to complete it.

Two events tie together the nine stories in Monic Ductan’s gorgeous debut: the 1920s lynching of Ida Pearl Crawley and the 1980s drowning of a high school basketball player, Lucy Boudreaux. Both forever shape the people and the place of Muscadine, Georgia, in the foothills of Appalachia.

The daughters of Muscadine are Black southern women who are, at times, outcasts due to their race and are also estranged from those they love. A remorseful woman tries to connect with the child she gave up for adoption; another, immersed in loneliness, attempts to connect with a violent felon. Two sisters love each other deeply even when they cannot understand one another. A little girl witnessing her father’s slow death realizes her own power and lack thereof. A single woman weathers the excitement―and rigors―of online dating.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the Summer 2024 Issue: Indie Summer Reads.