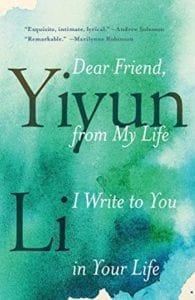

From an acclaimed fiction writer, this memoir looks at severe depression, the meaning of time, and the sustaining power of literature

Shelf Unbound: We’re talking about libraries in this issue of Shelf Unbound, so let’s start there. You write about being chosen as a librarian’s assistant while in middle school in Beijing, the first time you had even been in a library. “Within a few months, I had finished all the books on the literature shelves (the 800s, as I began to think of them).” Describe how this experience opened a new world to you.

Yiyun Li: I’ve always an obsessive reader. When I was younger, there was not much available to me, so I would read anything—newspaper wrapped around fish or meat, shoeboxes, a medical manual when I had measles in third grade. Going to middle school and having access to a full (though small) library was like a fairytale. We have a saying in Chinese, describing the happiness of decadence: like a mouse that has landed in a large jar of rice. That is how it felt to me then. A book mouse in a full room of books.

Shelf Unbound: Your memoir explores time, the sustaining power of literature, and your struggle with crushing depression. You write in the Afterword, “These essays were started with mixed feelings and contradictory motives. I wanted to argue against suicide as much as for it, which is to say I wanted to keep the option of suicide and I wanted it to be forever taken away from me.” I learned a lot about severe depression in reading this book, as I did years ago when reading William Styron’s Darkness Visible. Did you discover anything about yourself or your own depression in writing the memoir?

Li: I discovered that I was good at arguing against myself! As somewhere in the book I wrote: One always knows how best to sabotage one’s own life. But these are necessary, in my case. Going through severe depression and suicidal crises, one has to deal with medical procedures and interact with mental health professionals as well as friends and family who are concerned. But in a sense these are external factors. They alleviate symptoms but they don’t change who one is fundamentally. I don’t think this is a book with an arc, and by the end everything is resolved, just as I don’t believe mental illness can be magically cured. All the arguments in the book, all the self-dissection—these were done with the hope of recording an experience—the rational and irrational thinking, the arguments and counterarguments—which may be helpful in the future as a reference.

Shelf Unbound: You are a much-lauded writer of fiction, receiving among other awards a PEN/Hemingway Award and a MacArthur Foundation fellowship. How did your writing process differ in writing a memoir vs fiction?

Li: Writing fiction is much easier in that the characters and their stories are all that matters, and my own self is transparent, or as transparent as possible. So I am much less self-conscious when I write fiction. I follow my characters’ lead. I try to get into their minds. And there is an unlimitedness in experiencing how they experience. With a memoir, especially a memoir like this one, which is not a conventional narrative, I had to get rid of all the emergency exits so that self I was examining could not elude my scrutiny.

Shelf Unbound: What interests you in thinking about and reading about and writing about time?

Li:I often think that time is the most democratic factor in life–even birth and death don’t come close to that. Yet we experience time in a private manner. No two of us experiences a period of time—a day, an hour, ten minutes—the same way even if we are next to each other. I wonder if this difference in our experience leads to our yearning to be close to another person, to understand and to be understood, and to make connection.

Shelf Unbound: You write about the importance of literature in your life and include “A Partial List of Books” at the end of your memoir. If you were stranded on a desert island and could have just one book, which one would you pick and why?

Li: I read War and Peace and Moby-Dick every year, each book taking six months—I read one for sublime realism, and the other for sublime metaphors. So may I bring both?