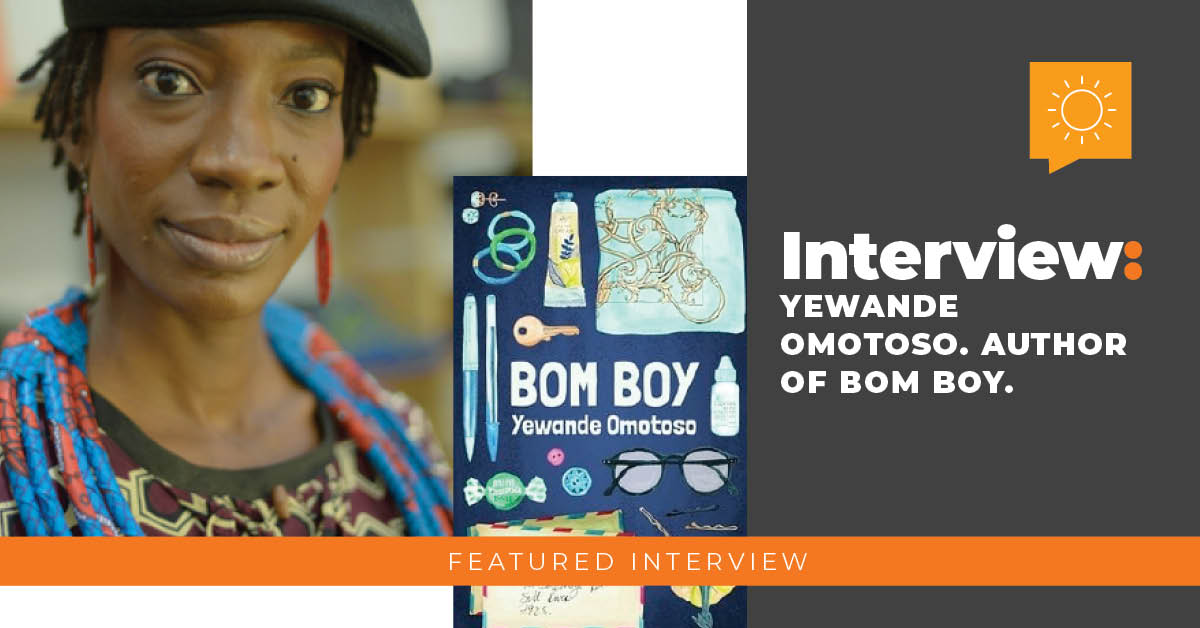

By Wyatt Bandt

An architect and writer, Yewande Omotoso received the 2012 South African Literary Award for First-Time Published Author with her book Bom Boy, and for good reason. Yewande creates characters that brilliantly reflect important and timely themes such as discrimination, loneliness, and hope while grounding them in pithy prose that makes reading a treat.

We are all influenced by our backgrounds—the places we grew up, our family, those we’ve admired or even stood against. Where do you see those influences informing your writing?

YO: I’ve never been able to see neatly where all the influences come from. I’m of three cultures, born in Barbados to a Barbadian mother and Nigerian father, grew up in Nigeria, and then lived in South Africa since I was 12 till now. I remember being read to from a very young age, specifically Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T. S. Elliot—my mom reading and the rhythms being emblazoned in my mind. Much older I would say writers such as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Zee Edgell, and George Lamming were the writers I was reading in my mid and late teens. Wole Soyinka and August Wilson’s plays. James Baldwin. Aminata Forna. Marie N’Diaye. Not sure if these are influences so much as writers I could read over and over. As I’ve started writing my own novels, Siri Hustvedt has somehow become a writer I really draw from, her attention to art and creativity, the elegant intellectual density, the strangeness.

Where did you find the original inspiration for Bom Boy?

YO: Inspiration too is another fuzzy thing. I wrote ‘Bom Boy’ as my master’s thesis at the University of Cape Town. It was the first novel I’d ever attempted to write. I started off wanting to write about a young boy who was ostracized, lacking connection. He sought it in off-kilter but also violent ways. Initial versions of the manuscript had Lékè kidnapping people believe it or not! But it wasn’t working, and I suppose this speaks to my belief in how the writing happens. I do believe that the story—with all its characters—already exists. And my job is to chisel it out of the stone so to speak. Sometimes I’m wrong—Lékè isn’t a kidnapper or a would-be serial killer—and then I have to wrestle with the text, keep chiseling until I find the thing that is true. But my intention was always to write about someone solitary, disconnected, longing for connection, but unable to solve that dilemma.

Throughout Bom Boy, I noticed an emphasis on sound, notably it being muted or absent altogether. I found this intriguing because it not only ties in with the themes of loneliness and solitude prominent in the book, but it also parallels how many of the characters communicate; they often talk around their problems or don’t talk about them at all. Did you set out to make these connections from the start?

YO: Looking at the two novels I’ve written since writing Bom Boy, I think I have an abiding obsession with the solitary figure, the trapped human being inside the somewhat functioning person, all the silences, all the unsaid, the pretenses. I’m obsessed with the possibility of repair—when it’s there and when it’s not. I won’t say I “set out” to write this, but it’s what bubbled up when I sat down to write; it’s what fascinates me. Those are the characters I feel compelled towards.

I was especially compelled by the character of Lékè’s father, Oscar. In contrast to Lékè and many of the other characters, I found him to be impulsively open and expressive, which adds to the tragedy of him never being able to meet or speak to his son. Could you tell us more about Oscar and how he came about?

YO: When I started writing Lékè, I had him as someone stuck who eventually becomes unstuck, and curiously, the character that became Oscar was initially imagined as simply an older unstuck Lékè. It was in writing class that someone suggested they might be two different people! One thing I love about my messy writing process is that I am not precious, I took that light suggestion and tried it on—indeed when I separated the characters the story moved. Oscar became Lékè’s father, a man brimming with all the expression and emotion Lékè longs for and lacks. He’s the love Lékè doesn’t get but needs and has to scrounge for as a young adult.

You’ve also written The Woman Next Door, which I’m looking forward to reading for myself, but I have to ask: is there anything else that you’re working on right now?

YO: I have a third novel coming out in October—An Unusual Grief published by Cassava Republic. I’m currently working on something that is more autobiographical which feels a departure from my usual fiction. The working title is Family Feeling, and it’s about the meaning of family, the different ways we find family, and what it means to belong.

To conclude, I want to ask you why you write. What drives you to tell stories like Bom Boy?

YO: I write like a rash that must be scratched; it feels natural for me to be grappling with the things of this world and others using words and stories. I always feel I’m a better person when I write, and when I fall into spaces where my writing slips, I don’t feel like the best version of myself. I write because it’s hard, because it feels good and makes sense. It doesn’t always feel like a choice. It’s a compulsion.

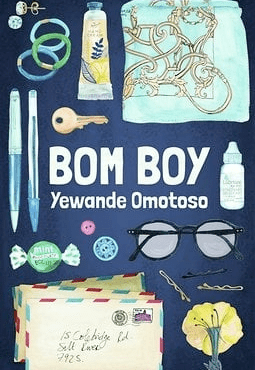

About the Book:

Abandoned by his birth mother, losing his adoptive mother to cancer, and failing to connect with his distant adoptive father, Leke–a troubled young man living in Cape Town–has developed some odd and possibly destructive habits: he stalks strangers, steals small objects, and visits doctors and healers in search of friendship. Through a series of letters written to him from prison by his Nigerian father, a man he has never met, Leke learns about the family curse–a curse which his father had unsuccessfully tried to remove. Leke’s search to break the curse leads him to strange places.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October / November 2021 Issue: Read Global.