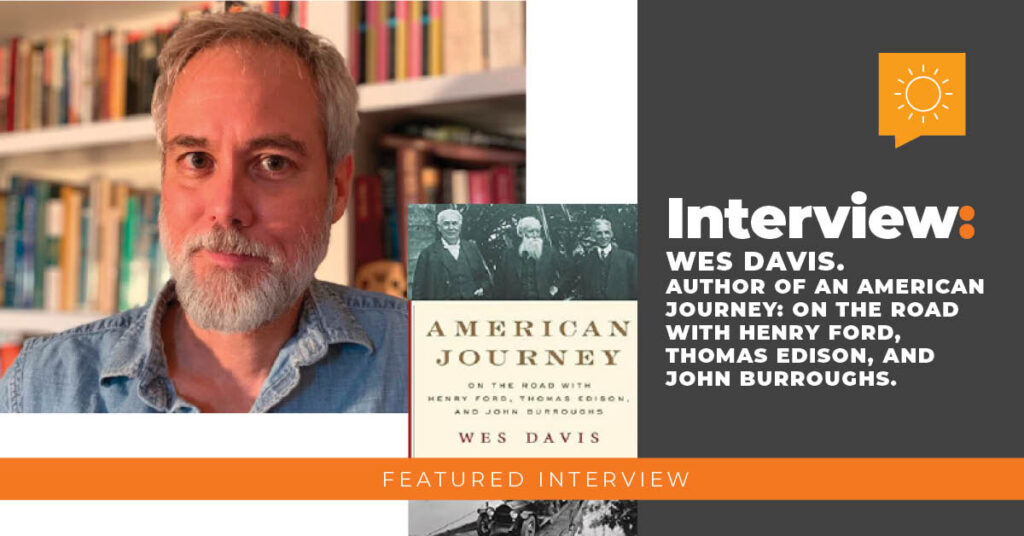

BY V. JOLENE MILLER

Wes Davis’ book An American Journey: On the Road with Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and John Burroughs takes readers to a crossroads between pre-industrial and modern America and intersects with a friendship between three men. Two of them (Ford and Edison) are responsible for the forward movement of the country while the other (Burroughs) is known for immersing his readers in nature. I had the opportunity to speak with Wes and learn about how he came to tell this story of a friendship that was cemented in time on the back roads of America.

I was intrigued by your book because it’s about road trips, and I love a good road trip. But I was also interested in the early 1900s historical aspect of it. Why these people? Ford, Edison, and Burroughs? Why this story?

WD: I got latched into this story through Burroughs, which I think is interesting because anybody who encounters the book is more likely to know Ford and Edison than Burroughs. My background is in literary studies, I was an English professor for a number of years, a literary critic, and a literary historian. I was digging through his letters and came across one in which he was telling a friend of his that Henry Ford had contacted him to say that he was a fan of his books and wanted to send Burroughs a Model T. Now I knew Burroughs primarily as a naturalist and conservationist, and I thought, Oh, he’s going to turn that down, it’s the last thing John Burroughs would want. I learned that not only did Burroughs accept the car, but he also became close friends with Ford.

Burroughs is somebody who had had friendships with a number of famous people. He went on hiking trips with Teddy Roosevelt. He knew John Muir. He was a close friend of Walt Whitman’s and friendly with Ralph Waldo Emerson. Although Ford represented a kind of modern age that was in a lot of ways antithetical to what Burroughs represented, Ford was still kind of the man of that era, in the way that maybe Ralph Waldo Emerson was the man of his era. Burroughs accepted the car, the two became good friends, and they wound up taking these road trips together. Then Thomas Edison comes into the picture.

As I got to know more of the story, I realized that this was an incredibly lucky thing to stumble across. We get to see these famous people doing things that they’re not known for. It also gives us this really interesting glimpse of a world in transition. So this is a moment when the United States is, for the first time sort of moving from a population that’s mostly rural and agrarian to a moment when most people live in cities. This is a really fascinating way to look at it because you have Ford and Edison, who are basically inventing this new world. They’re speeding up the pace of movement there. They’re shifting us from this life that’s lived according to natural rhythms. So we get to see this transition into their world through the lens of these trips in which, in the company of John Burroughs, this naturalist with roots in the 19th century, and links to the transcendentalist movement of Emerson and Whitman. Ford and Edison with him are basically escaping from that world that they were creating, which is the world that we now all live in.

You mentioned that a lot of people may not know who Burroughs is. How did you first become introduced to him?

WD: Sort of two reasons. Early in high school I had a friend named John Burroughs, but spelled a different way. His family was interested in John Burroughs and had several of his books on their shelves. I often raided their library because they also had the Harvard five-foot shelf of books or Dr. Elliot’s five-foot shelf of books, which was a Harvard entry into great books and publishing. And my friend John had that so I would often borrow books from him from that collection. One day, I found Burroughs’ first book Wake Robin, on one of those shelves, and started reading it. When I found that letter from him, I was sort of primed to be interested in that.

The other reason is in my earlier life, I was an academic. I knew ultimately I didn’t want to write academic books, I wanted to write for a broader audience. I moved from academia into writing for a trade audience by writing about writers who are doing things outside the study and had escaped from the library or escaped from the study and were doing interesting things out in the real world.

How long did it take you to write this book? What was that work like?

WD: I think it took four years. The contract I signed was for two years. I missed the deadline twice. Most of that time was spent doing research because part of what I wanted to do with this book was get enough sort of factual information about the trips to be able to relate the story in a narrative way I wanted to. Although everything in the book is factual, I wanted it to read like a novel. In order to do that, I really needed a lot of information. So most of the time was spent doing research.

I worked a lot at Vassar College, where they have, John Burroughs’s journals and his correspondence. A lot of the work was at the Benson Ford Research Center of the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn where they had an incredible range of artifacts relating to the story. I was able to find thousands of photographs. Many of them were dated and had the location written on the back. I could use the photographs to piece together parts of the story. I knew who the people were, who visited a particular camp on a particular day. The Benson Ford also had correspondence between Ford and Edison and Harvey Firestone, who’s the other figure in this story, and Burroughs. They’re putting the trips together – planning the trips, what the supplies will be, what kind of maps they’re going to use. I also went through newspaper reports. At this point in American history if Henry Ford and Thomas Edison are traveling through a small town, in a rural part of the country, every little newspaper wants to report it. I could track their progress through the newspapers and get these little glimpses of the trip.

So most of the writing was actually research. I spent a good two years doing research…maybe more like two and a half. Then a year and a half putting it together and rewriting it. This book, unlike my previous book, went through a lot of rewrites. I was so nervous about not being able to get enough information to give this rich narrative account, I wound up getting too much. When you have too much information, it’s almost as challenging as having not enough because as the researcher I wanted to get everything in there. But I had to recognize that a reader doesn’t necessarily want every single bit of information about this story.

That means you had to cut some stuff. How hard was that?

WD: I mean, it’s always hard. You hate it, but you can’t let anyone else cut it.

Most of the cuts were in a section on the trip that Ford and Edison made to the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. It made sense because they they actually traveled by train. It’s an important part of the story, because although the book focuses on one particular trip, which is this 1918 trip down into the Great Smoky Mountains, I look at several other trips over the course of five or six years leading up to that. One of them was this trip to the Panama Pacific Exposition, which shows the relationship between Ford and Edison becoming stronger and preparing the ground on which these friendly road trips can take place.

It also shows those two men looking at the world they invented. It was pretty much a celebration of American industrialism. Many of the things on display had actually been invented by Edison or developed by Ford. So it’s a great way of giving us a background story for them and allowed me to show what road travel was like in this country at that point. That was a big chapter. But ultimately, we didn’t need as much of Ford and Edison looking at every exhibit at the fair as I had been able to piece together.

What do you consider yourself most – a researcher, archaeologist, an educator, historian, or writer? How would you title yourself?

WD: I think, probably writer primarily, but the kind of writing I do lives on that bedrock of research.

What fostered your love for writing? Was it that five-foot shelf or something else?

WD: The five-foot shelf was the thing I had been looking for. I was an only child and grew up in the Appalachian South. At a time when there was obviously no internet. There was in the town where I lived very little television service. There were two channels if you tilted the antenna the right way. I became interested in books and basically spent my entire childhood reading. Even if I did something like camping or hiking, it was always a question like, which books would I take with me? How can I have whatever books I would need in any given situation?

And which books would you take?

WD: For many of those years, the book that I took more than any other was The Rose Walden – a book I took with me and read over and over and over for decades.

In the book, you described Ford’s worldview during this time period. Could you share a little bit about what it was like to write about?

WD: When I first discovered this story, my first thought was, I don’t really want to write a book about Henry Ford. Because the first thing people think of is the Model T. The second thing is his anti-semitism. Neil Baldwin wrote a great biography of Edison. He also wrote a book I was familiar with called Henry Ford and the Jews. I knew from reading that book what a difficult story that was. It wasn’t until I had read enough of John Burroughs’ journals to realize that Burroughs was himself repulsed by that part of Ford and that gave me a way to talk about it.

Early in the book, Ford, Edison, and Burroughs are following the Leo Frank trial in in 1914, in which a Jewish factory manager working in a factory in Atlanta is accused of a murder that took place in the factory and winds up getting railroaded. And there’s all sorts of anti-semitism around the trial. This is one of their first trips together, all three of them at Edison’s house in Fort Myers, Florida. And they all agreed that prejudice had played a role in the verdict and that Leo Frank had not gotten a fair trial. They all agreed that he should get a fair trial and that the guilty person should be found. So, you know, at that moment, I see that Burroughs and Edison are sort of influencing Ford. But over time, Burroughs is finally sort of fed up with Ford’s railing against the Jews. When they’re camped near Lake Placid, New York, he goes back to his tent and writes in his journal that Ford has been blaming the war on the Jews, has been blaming the Jews for violence and crime that kind of swept through the US in the wake of the war. …and Burroughs seems to have actually called him out on it. And then he goes back and writes about this in his journal. That gave me the perfect way to sort of deal with this.

What’s next for Wes Davis?

WD: I have a number of ideas simmering. I’m not sure what I’ll wind up on. This book was published by WW Norton, and I loved working for them. I would like to find an idea that they think is the right next book. I love this period – early 20th Century America. I also am very much attached to Greece and Crete. I have some other things cooking that might take me back to Greece but in the same time period.

Where can readers go to learn more about you?

WD: I have to admit, I’m sort of a social media-phobe. I recognize that at some point I need a website at the very least. At the moment, the only connection I have to that world is an Amazon author page. People told me, while I was writing this book, that I needed to have more of a presence. But I thought about how John Burroughs wouldn’t do that. So, while writing this book, at least, it felt right to stay in John Burroughs’ mode in the 19th century waiting for Walt Whitman to stop by.

What was your favorite road trip? Do you have a favorite that stands out in your memory?

WD: I’ve done a lot of them because I don’t like to fly. Yet another thing I share with John Burroughs. I’ve driven across the country several times, but more recently, I’ve tried to take trips that follow the routes of Ford, Edison, and Burroughs traveled. The best is one I did with my two daughters two summers ago. We drove down to Tennessee and drove over the Blue Ridge Mountains into North Carolina following a path that was very close to what Ford and Edison did…That’s a difficult piece of road to drive…The road surface is perfectly fine, but going through the mountains we encountered switchbacks that were just throwing us back and forth in the car…as we’re going through there, my daughters were clinging to the seats as they’re thrown back and forth. That was a great trip…in which the personal kind of overlapped with the Burroughs’ story.

And because every good road trip needs a car, what kind of car do you drive?

WD: That trip was in a Subaru Forrester. It replaces a Forrester that I drove for twenty years…When I get hold of a car, I tend to hang on to it forever and put a lot of miles on it. Before that, I had a ‘78 Volkswagon Bus.

American Journey: On the Road with Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and John Burroughs

In 1913, an unlikely friendship blossomed between Henry Ford and famed naturalist John Burroughs. When their mutual interest in Ralph Waldo Emerson led them to set out in one of Ford’s Model Ts to explore the Transcendentalist’s New England, the trip would prove to be the first of many excursions that would take Ford and Burroughs, together with an enthusiastic Thomas Edison, across America.

Their road trips—increasingly ambitious in scope—transported members of the group to the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, the Adirondacks of New York, and the Green Mountains of Vermont, finally paving the way for a grand 1918 expedition through southern Appalachia. In many ways, their timing could not have been worse. With war raging in Europe and an influenza pandemic that had already claimed thousands of lives abroad beginning to plague the United States, it was an inopportune moment for travel. Nevertheless, each of the men who embarked on the 1918 journey would subsequently point to it as the most memorable vacation of their lives.

These travels profoundly influenced the way Ford, Edison, and Burroughs viewed the world, nudging their work in new directions through a transformative decade in American history. In American Journey, Wes Davis re-creates these landmark adventures, through which one of the great naturalists of the nineteenth century helped the men who invented the modern age reconnect with the natural world—and reimagine the world they were creating.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the September / October / November 2023 Issue: Global Reads.