Author of The Lilac People

By Corinna Kloth

Set against the vibrant cabarets of Weimar Berlin and the shadow of Nazi and Allied persecution, The Lilac People explores queer joy, survival, and resilience through the story of Bertie, a trans man whose fragile freedom is shattered by war. In this conversation, author MT discusses the forgotten histories that sparked the novel, the balance of love and survival on the page, and the enduring relevance of queer resistance across generations.

The Lilac People transports readers to Berlin’s thriving queer underground during the Weimar era, then thrusts us into a post-liberation world where survival is still far from guaranteed. For readers unfamiliar with your book, can you share what drew you to tell Bertie’s story—a trans man who finds joy and safety in 1920s Berlin, only to see it shattered by Nazi rule and later complicated by Allied occupation? What was the spark that set this story in motion for you?

MT: The spark was a piece of information I came across on social media around 2016. It stated that when the Allied forces liberated the camps, they let everyone go except the queer and trans people, who they then sent to jail to start their sentences for being queer and/or trans. I looked this up to make sure it was true, and that became the multi-year research project that turned into The Lilac People. I realized that there was important information about the German queer community not just after WWII, but before Hitler’s rise to power, as well. I knew I wanted to show both ends of that timeline, and I felt the most effective way to juxtapose them was through the eyes of one character.

Your novel pulls from real queer history, from the Eldorado Club’s cabaret scene to the early Institute of Sexual Science, and the brutal reality of queer persecution under both Nazis and Allied forces. What research most changed how you saw this era, and how did you decide what factual details to weave directly into the fictional narrative of Bertie, Sofie, and Karl?

MT: My knowledge on queer history for this particular time and place was sparse before I started researching it for this book. So I guess I could say that virtually everything I learned changed how I saw the era. I never realized there was such a vibrant queer community at the time, and how it was the capital in the colonized world for queer rights, progress, culture, gender-affirming care, etc. But I was equally surprised to learn how there was so much persecution not only by the Nazis, but by the Allied forces thereafter.

I’m someone that tries to go by facts first. I don’t truly start mapping out the plot until I feel I’ve found as much historical information as I can. Then I try to create a plot around the most important pieces. It’s impossible to balance 100% historical accuracy with a fully engaging fictionalized plot, though, so there were a select handful of times where I had to make historical changes for the sake of the story. I tried to avoid making changes whenever I could, but when I had to, I made sure to note them in the back of the book. It’s important to me for readers to understand what was real and what was changed.

At its heart, The Lilac People is not just a war story, but a love story about Bertie and Sofie building a fragile life together while hiding their truths. How did you navigate the tension between romance and survival—between writing tender moments of love and the constant threat of betrayal or capture?

MT: People’s eyes may start to glaze

over as I try to explain this, but here we go. I’m a hardcore planner to the point that I not only map out every scene before I begin writing, but also put together different kinds of charts and graphs. One of them is a line graph where I map the intensity of each scene. If a scene is high in tension, it goes up higher on the graph. If it’s low in tension, it goes lower on the graph. I also include a second line on the same graph, again with highs and lows, but this time with positivity or negativity. The more upbeat a scene, the higher I place the scene on the graph. The more depressing a scene, the lower I place it on the graph.

Looking at those two lines, especially together, helps me visualize where the story may need some work or rearranging. For example, if I have several scenes in a row that are high up on the chart, that may mean there’s too much intensity going on for too long, and it’ll likely wear out my reader. Or if several scenes in a row are low on the chart, that may mean there’s too much depressing stuff without giving the reader a break, and so I should add in something lighter or more endearing. And then there’s the whole business of how the two lines intersect with each other per scene, and you end up with various combinations of intensity and positivity/negativity that I get an odd enjoyment out of juggling.

One of the book’s most startling turns comes after the war, when “liberation” is not the freedom many imagined, especially for queer people. The arrival of Karl, a young trans prisoner freed from Dachau, triggers new dangers under Allied forces. Why was it important for you to explore this lesser-known history of post-war oppression, and how do you hope it reshapes readers’ understanding of this period?

MT: Once I learned about this history, I couldn’t let it go. I’d wake up in the middle of the night thinking about it. Out of all the trans history I’ve researched over the years, this spoke particularly deeply to me. Despite all the attempts at erasure in all its ways, plenty of documentation had managed to survive through the sheer will of the community.

I wanted to write this book in honor of all these folks, nameless or otherwise, having survived the war or not. They were all equally important, and I felt the best way I could honor them was to get this history into the mainstream the best I could. So much of what this community did benefitted the rest of the trans community right up to the present day. I wanted to show my thanks by doing my part to make sure they were no longer forgotten.

That’s ultimately what I hope readers get from this period: remembrance for these people. That, and the realization that what we think we know of history likely isn’t the whole story. Plenty of history gets coopted, erased, washed, etc., but is nonetheless presented as the (whole) truth. I hope The Lilac People opens people’s eyes.

Your title nods to Das Lila Lied, an early 20th-century German anthem for sexual minorities. How did this piece of music influence the tone or spirit of your book? Do you see Bertie and Sofie’s story as a lyrical act of defiance?

MT: The interesting thing about planning is no matter how much I map out my plots, they’ll always surprise me. The song wasn’t originally intended to play such a major part in the book, but rather was put in for flavor as the first known queer anthem. But as I wrote the rough draft, it took on a life of its own. Bertie, Sofie, and Karl all got into it, and I let them take the wheel. By the time I started the second draft, I wove in the song with more intention, using it as symbolism for defiance, joy, community, found family, etc. It ended up thematically doing heavy lifting for the entire story. I can’t imagine the book without it anymore.

The book moves between the electric, vibrant energy of pre-war Berlin and the hushed, perilous quiet of life in hiding. As a writer, how did you build these contrasting worlds? Did you write one timeline first or weave them together as you went?

MT: I mapped the timelines out separately to make sure they each made sense on their own, then wove them together in ways that best worked with the book’s pacing and the divulging of information. Charting things out, such as with the line graph I mentioned earlier, was particularly helpful.

In some ways, though, the juxtaposition of the two worlds wrote themselves, purely by historical accuracy. For example, the 1932/3 timeline mostly takes place in the winter, while the 1945 timeline mostly takes place in the spring. While the seasons are arguably opposites of their timelines—the happy stuff is taking place in the winter and the sad stuff is taking place in the spring—they’re indeed opposite of each other, and so I went with this irony and played up the feel of each season to further the feeling of difference.

Once I started writing the actual rough draft, though, I wrote the scenes one after the other in the order I intended the reader to read them. This approach helped me with flow between timelines, instead of writing each timeline separately and then trying to splice them together.

Your characters grapple not just with external persecution but with internalized fear, survivor’s guilt, and the burden of secrets. What was the most emotionally difficult scene for you to write, and how did you keep the story authentic without overwhelming the reader with despair?

MT: Hands down, the most difficult chapter for me was what I refer to as “Karl’s Monologue.” (If you know, you know.) It’s a short chapter of maybe—I don’t know—all of four pages, but it was rough. The research for that part alone took me maybe a full year of hunting, due to the heavy amount of destroyed documentation and evidence.

Then when it came to writing the chapter, finding the balance between authenticity and readability was particularly tough. On the one hand, I wanted to truly honor what these people went through by presenting it without flinching. On the other hand, if nobody read the book because of this, exactly how was I helping honor these folks? I can get the story out there, but I also need folks to actually read it.

Since the subject matter of this chapter was particularly traumatizing, I decided to pull back on it. I didn’t lie or sugarcoat anything, but I also didn’t get graphic. Plenty of details and additional information didn’t make it in because I realized the gist was more impactful, forcing the reader’s imagination to fill in the blanks.

I did, however, do something deliberately mean: I removed all white space. White space gives a reader’s brain a moment to breathe, break away, and process what’s on the page. But since the people who actually endured these things didn’t get a break or relief, I decided my reader wouldn’t either. I also presented the information in a halting way, in short sentences since that’s how Karl is speaking these things as he disassociates. This worked well because it not only is part of Karl’s personality, but also forces readers to pay particularly close attention. You can’t look away, you can’t take a break, you’re locked in.

So definitely “Karl’s Monologue.” The research was the hardest, the subject matter was the most exhausting, and the writing and editing were particularly meticulous. I was so glad when I never had to look at it again.

Though set nearly a century ago, The Lilac People feels alarmingly relevant in today’s climate of rising anti-trans rhetoric and attacks on queer rights. How do you hope readers connect Bertie’s story to current events? Were there modern echoes you felt compelled to underline—or did they surface naturally as you wrote?

MT: The Lilac People was never meant to be timely. Back when my publisher chose my release date, we didn’t know the world it’d debut into. But that said, there’s certainly plenty of overlap between the time period of my book and our current era. But believe it or not, those overlaps wrote themselves. I simply presented the book in its organic time and place. Any overlaps are simply our modern era’s doing.

Even though I was researching and writing this book essentially in step with the Trump era, and I often saw parallels, I deliberately didn’t write toward that fact. I wanted to present the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany in their natural forms, not only for their own sake, but also because I worried trying to deliberately reflect our current times would, well, come off like I was trying to reflect our current times. And then the book would’ve risked coming off preachy, inauthentic, and other things that went against the purpose of me writing The Lilac People. So I left well enough alone and let history itself do the talking.

All that said, plenty of readers have (understandably) been concerned about our modern times since reading The Lilac People. In response to that, I’ve recorded a free, online course called “Modern United States vs Nazi Germany: A Comparison Guide for Wellbeing.” It’s a deep dive and more information than you could imagine, but it’s everything I collected over the years. I sincerely believe knowledge is power, so I felt the best thing to do was share what I have with the world.

(Spoiler: We’re doing way better than Nazi Germany ever did. It’s not all sunshine and butterflies in the US right now, and people have gotten hurt and will continue to get hurt, but we’ll never get to the point Nazi Germany did. If you don’t believe me, go listen to my course. We have a lot of work ahead of us, and hopefully this course helps people understand where to direct their energy for resistance.)

Many queer and trans stories from this era were erased from history. Question: What responsibility did you feel in giving voice to these lives? Was there a moment where you thought, “This story must be told, even if it unsettles people”?

MT: I had a strong drive to give voice to these lives as soon as I learned given information. And the more information I learned, the stronger that drive became. It was less about responsibility and more about anger. I was so angry on behalf of these folks; not just with what they endured, which would’ve been bad enough; and not even just that the Nazis tried to destroy all evidence of their crimes thereafter, which also would’ve been bad enough; but then self-described heroes such as the United States deliberately followed in the Nazis’ footsteps for cruelty toward these communities. My communities. I knew I couldn’t, and wouldn’t, play a role in continuing that coverup and silence.

But I also knew that the US population of today isn’t the same as the US population of then. Even if our government hasn’t improved much, plenty of folks in the US are open to hearing more about queer and trans identities, and I was optimistic that readers would take interest in The Lilac People.

But back to anger. I can be spiteful sometimes, and I let it shine during this whole process. Whenever I wanted to give up because of the amount of work and overwhelm this project created, I’d think about these folks, what they’d gone through, and how they’d been silenced. And then I’d get right back to it. This was the most difficult book I’ve ever written, but they’re the ones who carried me through it.

For someone who’s never heard of The Lilac People before picking up this interview, What do you hope they feel or understand after reading Bertie, Sofie, and Karl’s story? If they remember just one image or emotion from the novel, what should it be?

MT: Aside from new knowledge on a particular time and place of trans history, I hope what stays with folks the most is the final imagery—which I obviously can’t say much about here—as well as the party scenes. I hope people take away from this the fact that the trans community has had plenty of joy in the past, but also that we can endure quite a bit. Community is vital in times like these—whether Nazi Germany or the modern US or elsewhere—and it’s what will see us through. Support each other, honor each other, and do the best you can. This isn’t the first time we’ve gone through something like this. And in a way, that means we’re never enduring difficulty alone.

As my unintentional tagline has since become: The ghosts of history are watching, kissing our foreheads.

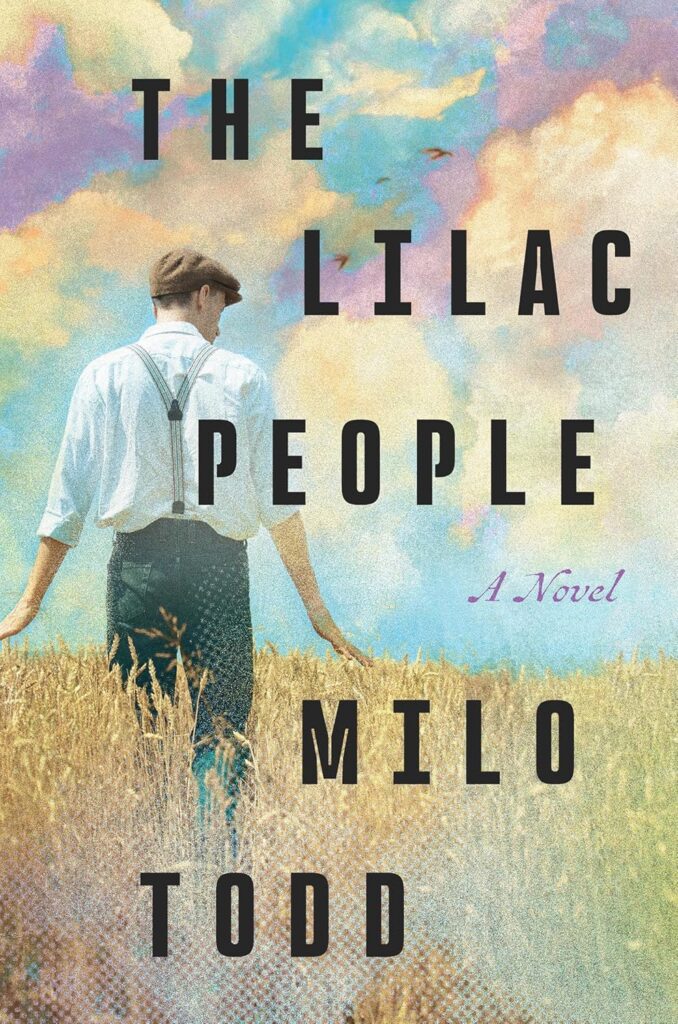

The Lilac People

Milo Todd

A moving and deeply humane story about a trans man who must relinquish the freedoms of prewar Berlin to survive first the Nazis then the Allies, all while protecting the ones he loves

In 1932 Berlin, a trans man named Bertie and his friends spend carefree nights at the Eldorado Club, the epicenter of Berlin’s thriving queer community. An employee of the renowned Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld at the Institute of Sexual Science, Bertie works to improve queer rights in Germany and beyond. But everything changes when Hitler rises to power. The Institute is raided, the Eldorado is shuttered, and queer people are rounded up. Bertie barely escapes with his girlfriend, Sofie, to a nearby farm. There they take on the identities of an elderly couple and live for more than a decade in isolation.