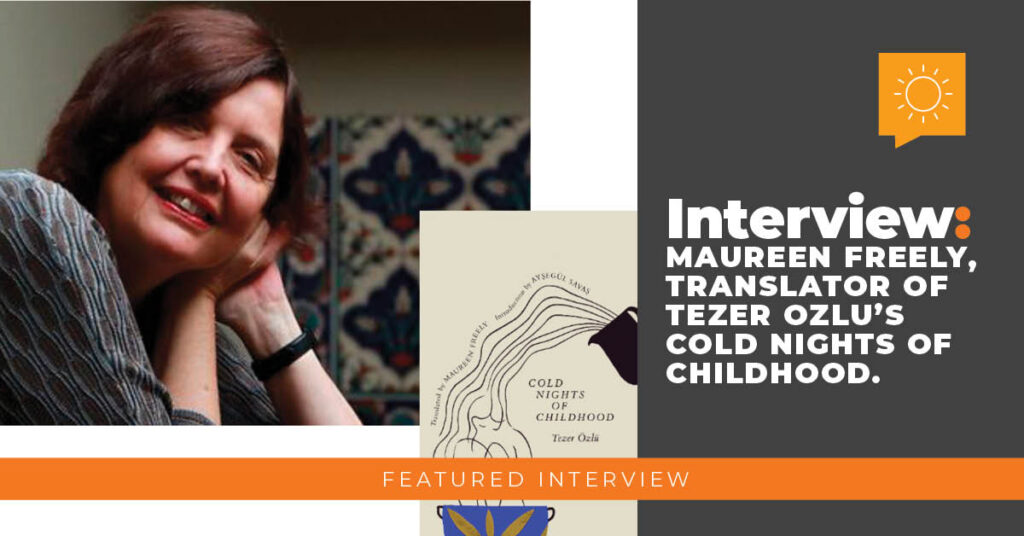

BY Wyatt Bandt

I had the opportunity to sit down with Maureen Freely, the woman who translated Tezer Özlü’s Cold Nights of Childhood. Maureen shared with me about how she started in the trade, the charm of it and how her experience as a novelist lends itself to her work.

WB: So! How did you begin working in translation?

MF: I’ve been translating informally since the age of 8, when my family moved to Istanbul, and it emerged that I picked up languages easily. I did my first proper translations in my 20s, while I was working as a secretary at Amnesty International. Mostly these were accounts written by political prisoners. I was already writing my own novels by then. I was struggling with my sixth novel (while making my living as a journalist and teacher) when my friend Orhan Pamuk asked me to translate Snow. And that’s where it all kicked off.

WB: How did you come to translate Cold Nights of Childhood?

MF: I am one of the lucky ones. A few years after we started working together, the author of my first published translation won the Nobel Prize. He kept me very busy – I translated five of his books over five years. After that I was in the enviable position of having more offers than I could handle. I have certainly never had that problem with my own novels! In any event, I always need to make time for my own work, my family and my overwhelming day job, so I almost always say no. But I fell in love with Cold Nights and could not let it go.

WB: Tezer Özlü passed away in 1986. What was it like translating a book when you weren’t able to communicate with the author?

MF: Communication with authors is not always easy! Particularly if their English is fluent but not quite as nuanced as they seem to think. As it happens, most of the books I’ve translated have been 20th century classics that should have been translated into English many decades ago. It’s great that there is more interest in Turkish literature now, but there’s a lot of catching up to do. Oh, but how I regret never having had a chance to tell Tezer how much I cherish her writing.

WB: What does your process for translation normally look like?

MF: I take it page by page. Spending the most time on the first page. Each book, each writer, has a distinct music, a voice like no other. And until I have figured out how to bring that voice and that music into English, I do not let myself move on to page 2.

WB: What are some of the core differences of Turkish and English?

MF: Turkish is an agglutinative language, so a root noun typically carries five, six, seven suffixes in a

particular order. The vowel in those suffixes change to allow for vowel harmony. This makes the language flow more beautifully. Pronouns are genderless. There are no freestanding definite orindefinite articles and no verbs for to be or to have. There is, however, a very useful distinction between things I have seen with my own eyes, and things I have heard from others. And there is a reliance on the passive voice. I could go on, but you get the idea….

Were there any surprises or challenges while you worked on this book?

MF: It was a shock and a treat to find myself on one familiar street after another. Tezer was ten years my

senior, but we may well have crossed paths over the years, because we lived in many of the same neighborhoods. And one of her best friends was also a good friend of my father’s. So with almost every new page, there was the thrill of recognition.

Was there anything that had to be removed or changed that you feel the English doesn’t capture?

MF: The novel gives great importance to place, and Tezer’s place names will mean a great deal to Turkish readers but very little to

readers but very little to anyone else.

Rather than remove them or attempt to overexplain them, I wrote an afterword to give a sense of the novel’s geography. There is also a glossary of place names, which will, I hope, make it possible to distinguish between the Istanbul locations and the towns elsewhere in Turkey that she also mentions.

WB: What’s it like balancing the author’s voice, style, cadence as you translate it into a different language?

MF: Because I am a novelist first and foremost, I go where I go in my own fictions. After absorbing the

Turkish words, I dive deep down, do my best to understand what sort of artistic effect the author might

have been after. Then I swim to the surface and try to create that same effect in English. The emphasis

being on the word try.

WB: Are there any ways you feel the English version of the book differs from the original?

MF: I hope not!

WB: What did you like most about Cold Nights of Childhood?

MF: I like (love) the way she chops and changes the rules of grammar and narration to evoke a particular

state of mind – ever changing, ever swinging to extremes. She was bipolar and suffered a great deal at

the hands of the medical establishment. She describes her ordeals unflinchingly, but here is another thing I admire about her way with autofiction: she refuses to be contained or defined by what has been done to her. Her eyes are always on the beauty that is just beyond her reach, if not her understanding.

WB: What are you reading right now?

MF: Time Shelter by the Bulgarian novelist Georgi Gospodinov, which won this year’s International Booker. It’s sublime – and timely.

WB: What do you love about translation?

MF: When I’m translating, I’m no longer a foreigner in the country of my childhood. I am free to roam discover, question, rejoice and grieve. After my husband died very suddenly some years ago, I went into translation for company and consolation. If I think back on the dozen or so books I’ve translated since then, I cannot find a single one that isn’t sad. That doesn’t acknowledge my own sadness, and give me back my heart.

Is there anywhere people can follow your work?

MF: My daughters keep promising to build me a website. Maybe next year. I’m not on Twitter – too many friends destroyed by pile-ons.

“A profoundly moving account of desperation, exhilaration, and endurance.”–Kirkus Reviews

The Bell Jar meets Good Morning, Midnight, by one of Turkey’s most beloved writers.

The narrator of Tezer Özlü’s novel is between lovers. She is in and out of psychiatric wards, where she is forced to undergo electroshock treatments. She is between Berlin and Paris. She returns to Istanbul, in search of freedom, happiness, and new love.

Set across the rambling orchards of a childhood in the Turkish provinces and the smoke-filled cafes of European capitals, Cold Nights of Childhood offers a sensual, unflinching portrayal of a woman’s sexual encounters and psychological struggle, staging a clash between unbridled feminine desire and repressive, patriarchal society.

Originally published in 1980, six years before her death at 43, Cold Nights of Childhood cemented Tezer Özlü’s status as one of Turkey’s most beloved writers. A classic that deserves to stand alongside The Bell Jar and Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, Cold Nights of Childhood is a powerfully vivid, disorienting, and bittersweet novel about the determined embrace of life in all its complexity and confusion, translated into English here for the first time by Maureen Freely, with an introduction by Aysegül Savas.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the September / October / November 2023 Issue: Global Reads.