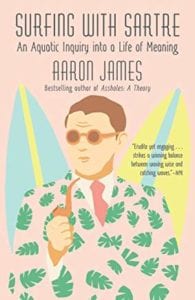

Author, Aaron James, begs to differ with Jean-Paul Sartre, who once declared waterskiing to be “the ideal limit of aquatic sports.”

Penguin Random House

penguinrandomhouse.com

Shelf Unbound: Sartre famously said in his seminal work No Exit that ‘hell is other people’ yet surfing tends to be made up of communities- it seems a disconnect, please speak to this seeming dichotomy, couldn’t surfing be considered an elite past time, available to the more well heeled—if so wouldn’t this fly in the face of Sartre’s general philosophy?

Aaron James: A surfer on in a crowded line-up can definitely relate to Sartre’s “hell is other people” sentiment! But Sartre thought people can’t really ever really recognize each other, not in a sustained way. What the surfing line up brings out, though, is that the conflictual hell is a product more of circumstance than of the human condition itself. Maybe the tide changes and the waves turn on and everyone is getting a few. The surf-line up hell can quickly turn to stoke and bonhomie all around. That guy I was giving stink eye an hour ago, whatever! We’re scoring, now maybe hooting each other on. So my idea is that surf etiquette already does a lot to create orderly relations of mutual recognition, and most of the time, the human condition isn’t Sartre’s hell. It’s actually really fun, and something to be grateful for. And, yes, maybe surfing is mostly for relatively affluent people who are fortunate enough to live near the coast. But, for almost anyone, being together with others in nature, maybe fishing down at the lake, can be a big part of why life is meaningful in and of itself, lived for those moments, for its own sake.

Shelf: You talk of surfing and flow stating that the surfer acquiesces to the shifting moments by giving up the need of control but isn’t control the only way to stay on the surfboard?

James: Definitely—as far as basic control of the body and surfboard goes. But as every surfer knows, that’s a small part of actually riding a wave, let alone riding a wave very well. Once you’re beyond basics, a lot of surfing involves letting go of the need to control and just watching, moment by moment, to be better attuned. It’s when we can respond in an attuned way to the shifting moments of the wave that “flow” happens, as a coalescence of skill and circumstance. That isn’t just a state of mind—you really are flowing through the wave sections. But, as surfers know, being in wave’s flow brings a profound sense of joy, a sense of fortune or gratitude—a feeling of being very glad to be alive, rather than not, just to be there for it. That, I think, is the essence of “stoke.”

Shelf: Please expand on your argument of surfer class versus workaholics.

James: If climate change is one of our big problems, then working too much is also a big problem. Work for money is one of main ways we create greenhouse gas emissions. So if you’re willing to work less and do something less consumptive instead—like go surfing—you’re actually contributing something to society! Surfers aren’t lazy, no good, good-for-nothing, freeloaders who should really get a job They’re the new model of civic virtue. The workaholic is the new problem child. Still, okay, maybe it wouldn’t be cool to force the workaholic to work less. That’s fine, too, as long as enough surfers are surfing to “offset” their emissions, keeping our overall work hours down to some acceptable low average. It sounds odd to a culture reared in the Protestant Work Ethic, but workaholics are in that way parasitic on the surfer’s making his or her distinctive contribution to society.

Shelf: Sartre speaks of skiing as the perfect experience, do you feel he would have continued to believe that had he experienced surfing? Why?

James: Sartre has these great passages in Being and Nothingness about skiing and waterskiing and why it exemplifies freedom. You get the sense that he almost found his way to what’s special about surfing, by pure reason! At the same time, when you really think hard about why surfing is freedom, it causes problems for his view of freedom as self-creation from nothing. Freedom in surfing is much more about attunement to what is beyond your control, and the flowing dynamic that emerges from it. So I think Sartre would have at least found surfing totally fascinating, and, who knows, maybe he would have changed his view of freedom itself.

Shelf: If surfers surf for the joy of the activity, the command of man over nature, if you will, do you think Sartre’s philosophy would validate or invalidate pursuing it sheerly in the pursuit of pleasure? Expand!

James: Sartre might see surfing as valuable in the way climbing to the top of a mountain is valuable. You did it, you owned it, which only testifies to your power in action. But I think Sartre would have appreciated that the joy of flowing attunement in surfing comes precisely from giving up any need to be so controlling or domineering. You’re just present with the wave, responding moment by moment, and good things just happen. It’s beautiful, and sublime, and eminently worthy of one’s limited time in life. If Sartre had seen that, I think he would have found a way out of his rather dark existential predicament.