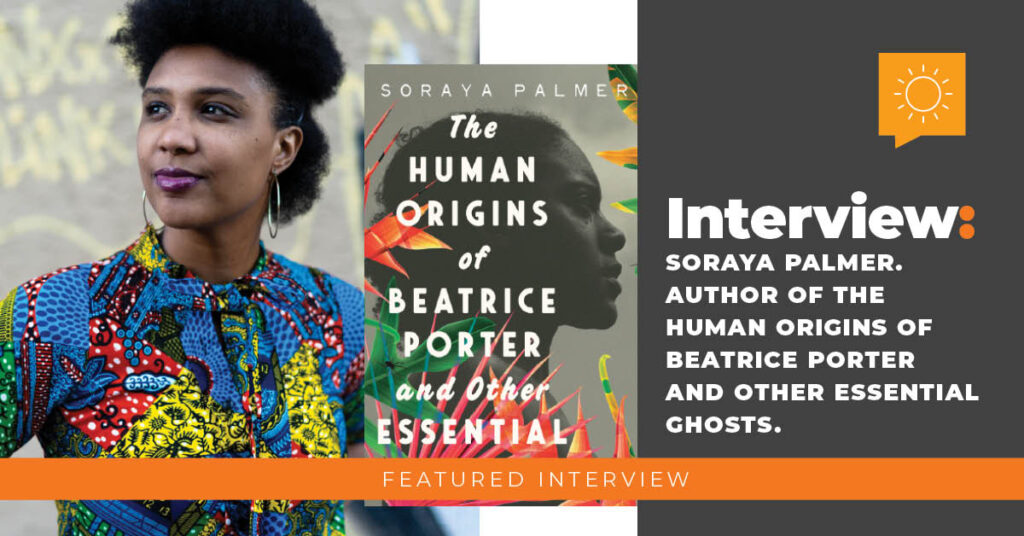

Thank you for joining us today, Soraya, I’m excited to discuss your novel The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts for our upcoming Voices issue. I also want to thank Catapult for arranging this interview on such short notice.

Congrats on your debut novel, a task worthy of praise no matter how many an author writes. What kind of obstacles did you encounter while reaching your goal?

SP: I wanted to give up a lot of the time. Sometimes it felt like my novel would never become exactly what it needed to be, which is to say one big obstacle was trying to maintain the ability to believe in myself for the 8 years it took me to finish my novel (after starting it officially in my MFA program). The other obstacle is a lot of things that could be easily summarized as capitalism—the ability to work a full time job, complete a second master’s degree and contend with all the physical and mental health challenges that come with existing while Black makes it very difficult to complete what already is a grueling process when writing to publish.

As the family dynamic deteriorates—sisters Zora and Sasha Porter begin to drift apart. As they grow up in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood, they realize they know little about their Jamaican father Nigel or their Trinidadian mother Beatrice. However, once the novel starts to analyze Nigel and Beatrice as children before they meet as young adults. What prompted you to write this book in a phantasmagoric and folktale style?

SP: I grew up listening to my parent’s stories—stories that featured ghosts. My mother told me about the lagahoo who is a half human, half animal shapeshifter who walks at night. My father would tell me stories of the Rolling Calf, a creature that looks like a bull with fire coming from his mouth and a chain for a tail. These stories appeared in one form or other in this book. I wanted to write a book that showed the ways that stories can show up in a family’s life as if they are a separate character—and show the ways that these stories can sustain those families, and how those families in turn kept these same stories alive.

Sasha leaves college to care for her ailing mother now that their father has left. Was this scenario somewhat personal or did you find the topic fitting for the story?

SP: I never had to care for my ailing mother, but I was curious about the different ways people respond to grief. Zora, who tends to see the best in people, is someone who sometimes has to look away from the hard things. Sasha, who is often more blunt (creating friction between her and her parents) was better able to care for her mother, because she is someone who always sees things as they are and not as she necessarily wishes them to be. She takes on the grief of her mother and the other members of her family in ways that Zora is not always able to. I would say that I have been both a person who shuts down and looks away from pain and also someone who can’t look away—who takes it all in.

No family is perfect, so I really enjoyed how empathetic the family’s narrative was. What is it about love and pain that kept this family alive?

SP: Throughout history Black families have had to do so many things to get through trauma and oppression. For the Porter family, they tell through the pain—as in story tell; they use food and music and television. All these art forms are also forms of love that the Porters use to stay alive, yes, but also to live.

Due to her cancer diagnosis, Beatrice and her daughters eventually come together. What is it about closure and second-chances that arise when you least expect it?

SP: I don’t think we ever really get closure, but we do gain perspective for our past selves that we didn’t have before, and that can give us the kind of contentment we need when we talk about closure. In this way, we can always give ourselves the chances we need to move on.

The narrator has a powerful presence, but when she ends up not being death or entirely reliable. What was it about her mischievousness that gave light to the story?

SP: The narrator is a trickster who is known for mischievousness, yes, but is also known for play and for being able to tell the stories we try to hide from ourselves. And I think that is hopeful.

Zora and Sasha cope with the domestic violence their father inflicts upon their mother by invoking a world of make-believe. It’s no secret how children naturally do this to survive under precarious situations. Why do you think so many adults lose this mechanism, and end up turning to infidelity, drugs, and violence for reprieve?

SP: As adults we are taught that it is wrong to be uncertain and so we learn to fear the things we don’t know as fact. Without the ability to believe the seemingly impossible, to imagine a better world, it is no surprise we might turn to other things to cope.

What authors or author stories give you inspiration to persevere?

SP: So many! Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Edwidge Danticat, James Balwdin, Kiese Laymon, Angela Carter to start!

What hopes do you have for the next writing venture?

SP: I am working on a memoir in essays and also a trilogy for this book!

This may be a difficult question to answer since books are interpreted differently by its readers, but given what the characters have already laid out in the novel, what do you think happens to us when our stories are erased?

SP: As a Black woman living in America, having my stories erased isn’t something I have to imagine. As a kid, not seeing myself represented in much of the literature we were taught to read in school, not seeing myself represented in television—gave me this fractured sense of self. It’s hard to believe you can make it as a published writer or believe you can find true love or be accepted when you don’t see anyone who looks like you having that experience.

Thank you so much for sitting down with me, Soraya. I wish you all the best in your life and writing career. I truly hope your readership continues to expand the more people become acquainted with your work.