The epilogue to Paul W. Williams’ memoir, Harvard, Hollywood, Hitmen, and Holymen, contains eight lists of “important practical things” he’s learned in his over seven decades on this planet. Those lessons stem from experiences that read as sometimes wild, sometimes winsome, sometimes woeful, but all of them, as the reader finds out, are memorable to Paul. Actor Elliott Gould wrote of the book, “It’s funny. It’s sad. It’s exciting. It’s sexy. And it’s frightening—sometimes startlingly so—but it’s authentic and true with a great cast of characters, all real people.” The book will be published February 14, 2023 by The University Press of Kentucky.

Your experiences are abundant, and at one point you say that you “made a list of all the extraordinary events you could.” Did one in particular make you think about writing a book? What made you finally decide to write and pursue publishing?

PW: No, no, once I survived thirty years—a big surprise—I planned to write a memoir if I lived long enough. To empty my head of pictures and emotions as part of achieving a clarity before I died. So writing the first list of extraordinary events was just the beginning of the long-planned process. It was obvious to me that part of the preparation for dying was a letting go of the past, forgiving all, accepting the life cycle.

Piggybacking on that first question, out of all the experiences you had in your life, can you identify one as the most transformative? Why?

PW: Not one. If you pursue self-understanding, doors appear at the conclusion of each learning chapter throughout your life. The trick is not to be afraid to go through the next door. And the next, again and again. But to answer your question concretely, some of the most transformative: discovering the transcendental nature of masturbatory orgasm in the seventh grade and discovering a dozen years later that having unlimited wealth is not what it is cracked up to be. Certainly, encountering Mescalito and the vision teaching of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (the Dalai Lama’s principal teacher) were great expansions of consciousness.

Did you ever contemplate fictionalizing your story? What do you think memoir can do for this story that fiction cannot?

PW: One, no. Two, nothing. I think the power of this memoir comes from the rigorous objective truth of the reporting. It is hard to believe it is not fiction! Perhaps that is why I see “jaw-dropping” so often in reviews.

The book covers a lot of ground. What made you decide to go for breadth instead of focusing on one specific time or event? Did anything surprise you as you made your way through the memories of these experiences? Did anything not make it into the book?

PW: The great psychoanalytic historian, Erik H. Erikson, was my tutor at Harvard College and mightily impressed me with his re-imagination of studying the entire life cycle from childhood to impending death. Almost every night, the prior day’s writing sparked early morning detailed remembrances. I eventually learned to get up at three or four a.m.and write them down!

The existing text is about 280 pages—I had to cut another 280 pages of wonderful stories that did not directly contribute to my evolution. For example, I wrote about discussing not going to Vietnam with Oliver Stone, and I report his buddy’s night scope shooting Viet Cong on the riverbank, but I cut [this portion]: “Oliver tells me that when his company attacks a peasant village, they charge from the perimeter toward the hooches, shooting constantly, with hard erections and spontaneous ejaculations.” It followed the vignette of my father dying, so the death was relevant, not the sex.

Those vignettes and other writings are being published later this year in a separate book, Emissions, Omissions & Illustrations, A Paul Williams Anthology, edited by Paul Cronin.

I’m curious about your ideal reader. Does your book have one? Who is the target audience?

PW: Someone interested in the late 1960s and 1970s New Hollywood and who wants to go deep inside those times—deeper than Rock Me On the Water, for example. And a reader who is interested in how to reduce the influence of capitalism and ego in their life and how to embrace a transcendental point of view. I suppose the target audience is film students, teachers and scholars, progressive literary types, people interested in spirit, and seniors in their sunset years.

Readers will recognize a lot of famous names in this book. Why do you think you crossed paths with them? Did these folks influence you any more or less than the people readers won’t recognize? Do you still feel like “an unknown in the big leagues” at times?

PW: I wanted to understand first-hand how the world worked more than anything else. So I was always on a peasant’s private quest for wisemen and understanding. It led me to many teachers and lovers. If someone is included in this book, they were among my influencers, high and low. And now the “big leagues” have gotten as big as nature, Spinoza’s god.

Speaking of names, you talk about changing your last name from Goldberg to Williams to hide your Jewish identity, then feeling “not a bona fide member of the Christian world or of the Jewish world . . . an outsider to the outsiders.” Did you ever contemplate changing it back to Goldberg? In hindsight, do you agree with your Dad’s decision to change it? Have you managed to develop the positive identity that Erik H. Erikson spoke of?

PW: I contemplated it once or twice, but thought I was too deeply into my new persona. My friend Charlie Plotkin advised me eight years ago to “deal with the Goldberg thing.” That helped me to start writing this book. No. I would not do that to a seventeen-year-old in the midst of forming his identity. In the book I write, “My father did not know this fact or understand that his renaming of his son was a major wound. A disabled adolescent now goes undercover and tries to live his dream. Some scars never heal. Here I am, to slay someone else’s ghosts: all of his near misses, all of his disappointments, all of his years of want.”

I have made interesting progress [toward the positive identity] with the help of shrinks and actors and gurus, not to mention being on the wrong side of a gun.

Certain instances stood out to me, like when you went in to talk about your thesis. Despite not knowing the background literature and misunderstanding the question, you still received a “low-pass.” It’s like the universe smiled on Paul W. Williams. In a way, I felt like that idea repeated itself over the course of the book: sure, you had obstacles to overcome, but in the end, you were also lucky. Would you agree?

PW: Yes. I flew out of my mother’s car when I was three and landed thirty feet away in a snowbank. I followed the arrows on the trail to the top of the mesa when I was six years old and did not fall straight down to my death. My hot girlfriend turned out to be a major league heiress. When we married, they offered to buy me a California movie studio that was up for sale. And on and on and so it went, and that is another reason for writing the book, to accept it all.

Actor. Director. Producer. Writer. All of those (and more) describe you. Do those creative pursuits all fill different voids for you? Where do you think your strength lies? Where do you think the public would say your strength lies?

PW: I was a poor boy, trying to make my way in life but with a deep impulse toward essential truth. I was just an opportunist trying to find a path that made sense. My strength lies in my willingness to be weak. This book is really an attempt to deal with diminishing my notion of my lower self. It is a quest to find higher fulfillment than materialism while honestly enjoying each moment as much as possible, as Jean Renoir advised me when I was twenty-one. The public? My sense of humor and attention to detail.

What’s the main message you hope your readers take away from your memoir?

PW: Have a good time before you die (or maybe leave your body

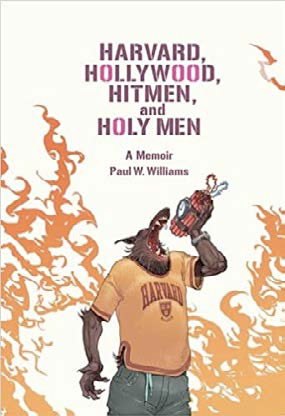

Harvard, Hollywood, Hitmen, and Holy Men: A Memoir

The movie director Paul Williams is a real-life Forrest Gump. Williams’ experiences form a unique and often wild constellation of encounters with star power, political power, and spiritual power―a life cycle that led to fame and fortune and to integrity and anonymity.

In a mad childhood created by an autocratic English teacher father and an infantilizing mother, he develops a precocious visual acuity to avoid wallops and a writing ability that mollified his father. This skill set wins him a scholarship to Harvard, where he needs to learn how the Wisemen think. He seeks out tutors who reveal themselves: Kissinger, Skinner, Galbraith, Erikson, Alpert, Leary, the Hubleys and Jean Renoir. Howard Gardner is his roommate and Michael Crichton is an editor friend on the college daily, The Crimson. After months, his lover reveals she is the heiress of a great American fortune.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the February / March 2023 Issue: Connection.