Grand Central Publishing

www.hatchettebookgroup.com

A gentleman answers the phone.

“Hello?”

“Hi, can I please speak with Pam Grier?”

“Just a minute.” Strains of opera music can be heard in the background. About a minute goes by, then faint shouting can be heard in the distance.

“Pam!” There is a long pause. “Pam!” Another pause. “Pam!” Another long pause. “Hurry up!” There is the sound of a ranch house screen door closing, then the male voice returns to the telephone.

“She must be down at the barn with the horses. Let me go git her.” There is the sound of heavy boots crunching on gravel, traveling a distance.

A muffled voice can be heard through the telephone: “It’s the lady from the magazine.” There’s some shuffling. The phone is handed over. Then the voice I’ve been waiting for can be heard clearly over the line. Coffy. Foxy Brown. Sheba. Jackie Brown. Kit Porter.

It’s Pam Grier, baby.

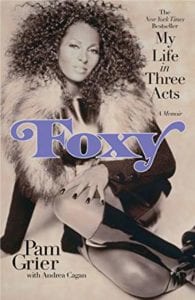

And she’s got a new book—her first—documenting her famous relationships (from turning down Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s marital ultimatum to the unique medical hazards of dating Richard Pryor), her miraculous recovery from cancer, her sexual abuse, her life growing up on the Colorado range, racism, resilience, and the extraordinary healing power of both horses and books.

We managed to catch up with her out in her barn, surrounded by said horses and rescue animals (“Come here, Zsa Zsa!”) just before she headed out on a cross-country trek with her nephew, all the way from her ranch in Colorado to Duke University, where he will be attending law school this fall. There can’t be much better than being dropped off on the steps of Duke Law by Auntie Foxy. —Kathy Wise

Shelf Unbound: Is it true that you taught Richard Pryor how to read?

Grier: I worked with him on his reading, but he did not completely learn under my watch. Through the light of his friends and family, he was learning to read phonetically. He wanted to read War and Peace, that was one of his life goals. He had a sixth grade education and he learned his scripts phonetically. But as talented as he was, learning to read was one of his greatest, greatest dreams.

That’s a personal dream for many people. To promote literacy, I encourage people to host book readings in their homes. Whether it’s my book Foxy or a book by Terry McMillan or another author, reading aloud brings books to life. I’ve read my book to several of my mom’s friends and I acted out the parts, giving a performance to these seniors who were waiting for the audio book. And it was a thrill just to see them enjoy my reading to them. I tell people read to seniors. Read to children. Read aloud.

Shelf: Your book tour has really focused on community bookstores

as opposed to big box stores. Is that intentional?

Grier: I want to keep our community bookstores open. Afri-Ware [www.afriware.net] is a wonderful store in Chicago, then there’s The Dock Bookshop [www.shop.dockbooks.com] in Fort Worth, Texas, and we have Eso Won [www.esowonbookstore.com] in Los Angeles. They are using their bookstores not only as churches on Sunday and as daycare, but they are supporting their communities and promoting literacy. The Dock even offers a Uhuru summer camp where children can learn Swahili.

So I see our communities knowing where we need to go, and we’re trying to fill in the gaps. People say we’re in a recession. I say, “So?” African Americans have understood squeezing a dime for the last 400 years. So we understand recession. We’re going to make it through this.

Shelf: Many people don’t realize that you grew up in Colorado, riding the range on horseback. Do you think that experience helped shape your sense of community?

Grier: My grandfather would come home from a fishing trip with buckets of trout and share it with the neighborhood. Deer from the hunt or vegetables from the garden, we shared. We didn’t have access to hospitals. If an ambulance knew where it was going, it wouldn’t show up in a black community. Emergency rooms? No, we got fixed in someone’s kitchen. We got taped up, broken bones set, tooth pulled, all in someone’s kitchen. My mama was always taking care of someone in her kitchen, all of the nurses were. “Let’s go see Miss Davis,” they’d say, and you’d get your tooth pulled or your eye fixed or scab closed up. We took care of each other. And now all of a sudden we got so wealthy we don’t need each other?

Communities are starting to come together again and stand up for themselves. I have seen it happen for myself. It has been the big hug of healing story. That’s why I had to get out and write my book and be enriched by my community.

Shelf: So what did you think when Quentin Tarantino told you he was writing a movie for you?

Grier:I thought, Yeah right, you just want to get in my thong. Sure, okay, he’s going to write about me, a movie. Yeah, okay, I heard that. He wants some, too.

So seven months later, what shows up in the mail but a yellow notice from the post office. I have an envelope, 44 cents due. I figure they’re selling mattresses or something. Then the next day, here it is again. An envelope from L.A. with 44 cents due. Who doesn’t have 44 cents for stamps? Go in your drawer, your pockets, find 44 cents. So I say okay, someone’s persistent about this 44 cents. So I taped the money to the sticker, they dropped off the envelope, and in the corner it says “Q. Tarantino.” I opened it. I pulled out Jackie Brown.

There’s a note: “Please read it, call and tell me what you think. Q. Tarantino.” It says it’s going to be low budget—he didn’t have stamp money— I’m doing it for scale with a back end of beer. I start reading it. The character of Jackie Brown is all the way through. It’s wonderful—look at the story, the scope, the twists and turns. It’s fantastic. And it’s been in the post office for three weeks?

It took him two years to write that movie. I didn’t do anything to deserve that. He said, “Yes you did. You did theater. I saw A Soldier’s Story at the Negro Ensemble Company the last year it was in existence in New York and I was moved. You did plays, the best and most difficult plays. You did Fool

for Love, it’s 90 minutes with no intermission. And in Frankie and Johnny in the Claire de Lune you’re nude on stage. You did the most wonderful plays, and I decided I wanted people to see your talent.”

I do a movie every 10 years if I’m lucky, but getting that film written by this incredible pop director of the world was something special.

Shelf: Why did you decide to write Foxy?

Grier: Before I wrote my memoir I read 20 books by others, from The Legs

Are the Last to Go by Diahann Carroll to The Measure of a Man by Sidney Poitier. And, of course, I read Stormy Weather, Lena Horne’s memoir. They all have something very special to share. And I realized for me, for my legacy, I wanted to humanize that advertising poster, that placard, all of the enigmatic characters I have become associated with. I wanted to humanize myself.

I knew I made the right move writing the book when I went on the book tour and found that many men were purchasing the book and reading it not only because they have daughters, but they also confided in me their stories of abuse as children. And it is quite interesting because we are talking significant numbers of men who have suffered abuse from family members, which I had suffered and describe in my book.

I don’t know what the men were expecting when they bought the book—there are no pictures like in Maxim or Playboy, nothing even close. They say they just want to see the intimacy of my life. And the fact is that they’re not buying bass fishing magazines or car magazines, they’re buying my book and saying, “Now I don’t feel so alone.” I think when people share their healing and their knowledge, others are able to heal.

In the book you read about the first traumatic event I suffered at 18 and the one at 21 years old, from a family friend who was coming to “guide me.” That day that 300-pound man could have broken my neck. And I fought him off. I walked on back to my job at lunchtime with my clothing torn, my hair disheveled. Scratched and bruised and battered, but alive. That was the day that I guess I became Coffy and Foxy and Jackie Brown and any woman who wanted to survive. I fought for my life.

Shelf: You write in the book that after the rape at age 6, “I found my only comfort zone was being alone and reading fantasy books like The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Alice in Wonderland. I liked nothing better than disappearing into my room and diving into a book that featured somebody else’s story and had nothing to do with me and my life.” What have books meant to you over the course of your life?

Grier: Education and escapism. Continued education and self-improvement is so important for your self-esteem. I found from reading I could go off to a place where I could just be. I could talk, I could speak, I could be beautiful, I could wear beautiful dresses, I could be a little girl again. I could do things without judgment, without kids picking on me.

You know, in my mother’s generation, my mom was turned away from so many things she wanted to do. Whether it was ballet school or music school. Thank God my music teacher came to our neighborhood. She took the bus to teach me. After my test she said, “You are wonderful, I will come to you.” I couldn’t go to her school. She would take the bus and walk from the stop and my grandfather would take her home at night. But she was willing to come across town to teach me.

Young girls today don’t realize how difficult it was, even for my mother and grandmother and great-grandmother. They didn’t get to go to architectural school, they couldn’t get into universities. It was a time when women couldn’t vote or drive, and if you were a woman of color forget it. All those lost opportunities growing up. I endured what my mom had endured. How the women in my family struggled just to get what degree they could get. My mom wanted to be a doctor. My aunt, Foxy Brown, she wanted to be an architect. Those doors were closed to them.

When I was reading, I could fantasize about where I could go and what I could be and how I could look and who I could talk to. There would be music and sound and color. A child could use, as I did, their imagination, and that was a form of freedom.