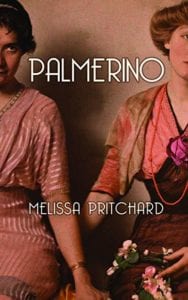

In a mere 192 pages, Melissa Pritchard has created a rich, lush, and riveting story of two women writers in different eras.

Shelf Unbound: What drew you to write a fictionalized account of the life of the rather obscure Victorian-era lesbian novelist Violet Paget (aka Vernon Lee)?

Melissa Pritchard: On a hot July afternoon in 2008, in the hills above Florence, Italy, I was introduced by an Italian friend to Federica Paretti, one of the members of the Angeli family who now own Vernon Lee’s former home. When the dark green door opening into the gardens of Villa il Palmerino swung back, and Federica, a former ballerina, extended her hand to greet me, I had the strangest feeling I had come home, that I knew the place. I returned the next winter to stay for two weeks, and would return two more times, staying longer each time.

During that first visit, Federica told me about Vernon Lee and the Paget family, and during my second visit, as I came to learn more about this extraordinary, nearly forgotten figure of late Victorian literature and literary life, I felt, rather than decided, that I was meant to write about her, not as an increasing number of scholars were beginning to do, but to tell a more private side of Vernon Lee, to explore the notion of genius loci, or spirit of place, that she was so fond of writing about. I was seduced first of all by the beauty of Villa il Palmerino and only later, with some initial resistance, began to research Vernon Lee’s life. Her brilliance and difficult temperament frankly intimidated me. In time, I came to understand that Vernon Lee and Villa il Palmerino were essentially one and the same thing, and that her difficult temperament was a kind of protective wall around an exquisitely sensitive, empathetic woman.

Shelf: In keeping with the times, Paget led a very closeted and, at least in your fictionalized version, largely chaste life. What do you think her life would be like in today’s times?

Pritchard: Various circumstances affected Violet Paget/Vernon Lee’s life. The male-dominated century into which she was born, the eccentric, if not bizarre, family in which she grew up, her own astonishing brilliance, and a less than favorable physical appearance which, today, could likely be corrected by orthodontic surgery. In rare photos of Violet, particularly as she grew into the writer she renamed Vernon, one can glimpse the condition some of her contemporaries, mainly men, cruelly referred to as her “ugliness.” An overdeveloped, misproportioned jaw lent her face an unfortunate look, particularly in light of the Victorian ideal of feminine beauty. I believe (intuit) that she suffered over this, was self-conscious because of it, and by way of compensation combined with her own passion for knowledge and superior intellect, compensated for what was considered an unpleasing visage by an incomparable gift of talk, a prolific outpouring of books, articles, and aesthetic treatises, and finally, a sexual distancing from her own body.

It is fascinating to imagine who Violet/Vernon would be, transported into today’s world of medical advancement, social media chatter, and in some cities and parts of the world, at least, a full respect for sexual orientation. If she lived in a city of literacy, liberal opinion, and acceptance of difference, of diversity, in London or New York, for example, I think she would thrive. I think she would be wholly loved and be able to return that love. She would be as famous now as she was then, perhaps more so, widely celebrated for her intellect and wit; I like to think that her unusual face, without surgical correction, might even be seen as uniquely beautiful. I came across a photograph of Vernon Lee, in her thirties, standing near her famous fireplace of pietra serena stone (for which she traded a large piece of her land), and was struck by how utterly handsome she looked, imposing, not a figure to be trifled with. I like to think that people today—literary people, intellectuals, musicians, artists—would adore her. I certainly do. And if I were to meet her, I know she would initially intimidate me, but that we would ultimately find an affinity in our common interest in the subjects of empathy, the influence of art on physiology, and the supernatural world, particularly as these play out in literature.

Shelf: You wrote a commissioned biography of philanthropist Virginia G. Piper several years ago. How does bringing a real character to life in fiction differ from writing a biography?

Pritchard: In writing a biography, I discovered that one is irrevocably shackled to facts and to chronology in a far more stringent and constraining way than when combining research with imagination and even with intuition, to write a fictionalized portrait of an historical character. With Vernon Lee, I took artistic license and often “felt” my way into what seemed to be the emotional truths of her life. In doing so, I was all too aware I was possibly drifting off course from the facts and possible realities of her life and actual character, but in the end, the story I was listening for, intuiting, took precedence over presumed facts.

With the Virginia G. Piper biography, a book commissioned by the Piper Charitable Trust, I knew I had to write a highly accessible story. I learned a great deal from the extraordinary example she set, yet I chafed at having to keep the style of the book, the way I used language, relatively simple and concrete. My imagination felt as if it was in a straitjacket made of concrete.

With Palmerino, I was free to follow undercurrents, impressions, flashes of knowing—and to use language and form in a painterly, sophisticated, even risky way. I felt truer to myself as an artist. It was an honor to write the biography of Virginia G. Piper, but it was a challenging, anarchical thrill to write Palmerino.

Shelf: Your story has a modern-day historical fiction writer, Sylvia, researching and imagining Violet Paget’s life. Where did the character of Sylvia come from, and how did you decide to structure your novel in two time periods?

Pritchard: Sylvia is very much me, exaggerated, tampered with, re-invented. At the time I chose to write Palmerino, I was feeling a similar loneliness, the death of both my parents, the loss of confidence in my future as a writer, as a heart’s companion to anyone else. My situation wasn’t as isolating and vulnerable as Sylvia’s, but I took certain aspects of my situation, exaggerated them and created Sylvia as my protagonist, a woman writer alone, aging, without familiar foundations or associations. I wanted her absolutely vulnerable to the ethereal presence of Vernon Lee, to “the great female soul that is Villa il Palmerino.”

I struggled with the form of the novel, how to structure it. I didn’t want to write a fictionalized biography, set into the past —that bored me, and I wasn’t sure I was capable of it. I felt it would take me 10 years and 500 pages. I did wish to convey my love of this gorgeous, haunted place, Villa il Palmerino, my sense that Vernon Lee is still very much present in her former home and unkempt garden. I was doing research for the book, reading Henry James’ Italian Hours, when I suddenly remembered his classic work, The Turn of the Screw, how much I had admired it, been affected and haunted by it. I had found the key, the way into the novel; I would try to write a supernatural tale, both in homage to The Turn of the Screw and as tribute to Vernon Lee’s own highly regarded supernatural tales. I would also focus on the two great loves of her life, Mary Robinson and “Kit,” or Clementina Anstruther-Thompson, rather than attempt to convey her entire prodigious life. In the end, one is wisest writing the book one would most want to read. With Vernon Lee and Villa il Palmerino, I did just that, though it wasn’t easy. As for the ghost voice of Vernon Lee in the short sections titled “V,” I literally heard a voice, particularly in the first entry, and merely wrote down what I heard. Like Sylvia, as I wrote, I increasingly felt Vernon Lee’s presence, her guidance.

When I was well into the novel, several revisions in, I read her supernatural tale “Amor Dure” and realized I was shadowing that story, the tale of a biographer, increasingly obsessed and overtaken by the subject of his study, a woman long dead. Perhaps it’s an archetypal story pattern, the biographer seduced away from living by his dead subject, but I was jolted to see myself so closely mirroring Vernon Lee’s own tale of ghostly possession and genius loci, the power or spirit of place.

Shelf: Did Paget’s writing style influence yours in writing Palmerino?

Pritchard: By today’s tastes, Vernon Lee’s writing style is dense, elaborate, even florid. It is as if her prodigious brain and all facts and thoughts in it are pouring, uncensored, onto the page. If she is today best remembered for her supernatural tales, it may be in part due to this problem of thickety prose in much of her work. She overwhelms her reader. I greatly admire her travel writing, her nature writing, and The Enchanted Woods and Other Essays on the Genius of Places is one of my favorite of her books. It was said that to travel with Vernon Lee, even on a day’s walk in the hills above Florence where she lived, was to have an entire world of arcane and fascinating knowledge opened to one. She could peel back layers of time, she saw history as a palimpsest, and could, with ease and enthusiasm, tell you everything about anything. Henry James once said she was the only person in Florence worth having a conversation with. But she was also incapable, it seemed, of editing herself. While her writings are today admired by an increasing number of fans and scholars, she is most definitely an acquired taste. In preparing to write Palmerino, I read a number of the books Vernon Lee had read and admired. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun and William Wetmore Story’s Roba di Roma were influential in helping to shape my style in the historicized sections written by Sylvia, and in the choice of words and diction “V” uses.

My own fiction has been described, equally praised and criticised, as dense and elaborate, so it was fascinating to read similar criticisms of Vernon Lee’s prose, yet to find myself, by comparison with her style, a paragon of economy, several layers or thicknesses less than her. Vernon Lee was a genius, her brain retained everything she’d ever learned, she read voraciously, spoke and wrote fluently in four languages—it took a great deal of effort not to be intimidated by such a radiant and large mind, not to feel she was peering critically over my shoulder as I wrote, to find the point of empathetic connection between us. Fortunately, I think I did.