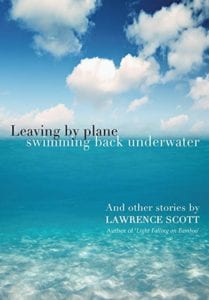

Lawrence Scott has been short-listed for Commonwealth Writers’ prizes three times, twice nominated for the International Impac Dublin Literary Award, and long-listed for the Whitebread Prize and the Booker Prize. A memorable collection of short stories.

Papillote Press

papillotepress.co.uk

Shelf Unbound: What’s a typical starting point for you in writing a story, for example the murdered dog in “A Dog is Buried”?

Lawrence Scott:With this story, there had been an event of finding a dead dog on a doorstep of a beach house that I had partly experienced. Also, I have always been struck by a Swedish saying: “There’s a dog buried,” much like the saying about skeletons in the cupboard. This got developed within the meaning of the story, the different burials within the story, suggesting that there was a past to be discovered and redressed. But quite soon it was the conversations that take place between Walter and Christian that became my main interest, and out of that grew their characters with their different pasts. Landscape, and what is written on the landscape, the history in the landscape is always a starting point and a point of development for me. Beginnings can be the voice of a character, as in the opening line of Ash on Guavas “This is a darling of an island.” They can be something as concrete as a photograph, as in the story, The Wedding Photograph. A report in a Trinidad newspaper inspired Incident on Rosary Street. The invitation to write about my sense of God stimulated the title story, Leaving by Plane Swimming Back Underwater.

Shelf Unbound: How do you develop your characters, such as Archbishop Sorzano and his fake miracle?

Lawrence Scott: As I was saying, once I get characters talking I listen to them and begin to find out what they are like. Archbishop Sorzano’s character develops in this way too, but there is also that initial perception told through the consciousness of Sorzano about the African tulip tree and the miracle of its flowering that was the original engine for the story. What can also happen is how another character, Mrs. Goveia, helps to frame Sorzano, who on the one hand is a modest man, driving a Mazda, but is also into his role as an archbishop signified by his ring and attitude to Mrs. Goveia’s serving of the morning mass. Once he starts talking with the prime minister the story takes off. I also draw on how satire develops and functions in the Trinidad calypso. That informed the rhythm and tone of the story, both in the dialogue and the description. There is a strong tradition about bringing down the powerful in Trinidadian satire, the mamaguy, which is topical, playful and irreverent. I find that once I’ve found the voice and the tone of the story, it writes itself, as it were. Of course, the hard work is in the editing and the re-writing.

Shelf Unbound: Do you have a favorite story in this book?

Lawrence Scott:I like a number of them because of the particularly different processes that produced them. Quite a few were commissioned for a BBC short story slot to be read in fourteen and a half minutes, and in a number of cases I read them myself. Reading aloud as I write is a very important part of my process in discovering voice, register and tone. Even though I use Standard English spelling, I often use Trinidadian dialect rhythms created through the syntax, and I need to keep hearing it as I progress through a story. A Little Something is a good example of this, as is Ash on Guavas and Coco’s Last Christmas. But even in stories with less evident dialect rhythms, I would claim that the standard is what I call Trinidadian standard. Trinidadians, even the most educated, speak along a continuum between a very evident dialect of English and Standard English, depending on the social and emotional contexts. I like to use this characteristic of our language. The form of the story interests me. In Tales Told Under the San Fernando Hill, which is a series of interconnected very short stories with their particular characters was an innovative approach for me. Creating fiction out of biography or autobiography is a challenge and at times very moving. The writing of Elspeth’s story in The Wedding Photograph, commissioned initially as a ghost story, is a favourite, partly because of the source of the story and then also because of what it is saying about our colonial history. The challenge of plotting the story grows out of the visits by the narrator to his cousin who is suffering from dementia. I have grown fond of the stories again, particularly while creating the collection with the help of my editor Polly Pattullo of Papillote Press. Placing the stories so that they speak to each other has been crucial, so that they seem to be bound together by the title Leaving by Plane Swimming Back Underwater, whichpoints to the theme of departures and arrivals in many of the stories and the tension created through the migration between the Caribbean and Europe.

Shelf Unbound: How do you find the entry point for your short stories, such as the first line of “The Last Glimpse of the Sun”: “She was one of these, pressing her loss to her breasts, carrying her exile in her heart.”

Lawrence Scott: I think I have covered some of my approaches in my previous answers to your questions, but I will add, that with this particular story, a very challenging story—the first line follows on directly from the epigraph which is taken from a collection of poems Filibustering in Samsara by the English poet Tom Lowenstein: “There are those who belong to their home and these others clinging to their exile.” “She was one of these …” This is one of the previously unpublished stories in the collection. It underwent many drafts and developed through a number of complex shifts both in time and place within the story and for me as I wrote it, as I travelled back from the Caribbean, and travelled between Sweden and England. I am fond of epigraphs and this one suggested itself early on in the writing, dictating that opening line. Location can infiltrate a story, for example using the Anglo-Saxon poem The Dream of the Rood as part of Iseult’s consciousness. This suggested itself because I was in that northern hemisphere at the time and it was indeed on Good Friday when I started writing an early draft, which I finished quite quickly during that visit to Gothenberg. I like the mix of cultural allusions in this story, moving between the Caribbean, 1960s England, South Africa, France, Kenya. This particular literary allusion to an Anglo-Saxon poem speaks to me still from my student days and a time when my religious experience as a Benedictine monk in the 1960s would have been a powerful influence. It continues to erupt through a vein or seam in the geology and archaeology of my writing.

Shelf Unbound: A short story is like ___________

Lawrence Scott: A short story is like a poem. What I mean by this is that short stories progress for me much in the same way that the composition of a poem might do. The progress is different to that of a novel, which is what I am mostly involved in writing. Embarked on the long haul, a novel will take me anything up to four years or even more to write, through complex research and several drafts. Poems and short stories have several drafts too, but I find, because the end is within easier reach, I move through the stages of composition as I would a poem, building gradually and holding all within a compact form. I suppose episodes within novels are like this too, but they have then to relate to the greater whole.

Shelf Unbound: What is the appeal for you of writing short stories?

Lawrence Scott:Well, some of my reply is in the former answer. I began my writing with short stories because they seemed like something that I could finish. I would not have to wait years for it to be completed. But, of course, while an apprenticeship is needed, short stories are not an easy thing to pull off. I have learnt that the skill is a craft all of its own. There is a rich tradition in the Caribbean short story, so I started there, in the footsteps of writers like Jean Rhys, Sam Selvon, Earl Lovelace and Vidia Naipaul. I also discovered in a wider Caribbean, the stories of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Some of my earliest influences are from that tradition. I like being commissioned to write a short story because it is an opportunity to write about a number of things you want to say but can’t always because you are involved in the ongoing novel. Commissioned to write a story to be published in the anthology Trinidad Noir gave me the opportunity to write Prophet, experimenting with that genre.I want to write about so much more than what I am writing in my current novel. But it is also, what I said earlier, that the short story allows you to experiment in form, very different forms. Many stories are begun in notebooks that don’t reach the light of day, and many more poems are filed in the bottom drawer of my desk.

Shelf Unbound: If you were teaching a course on short story writing, what is the primary piece of advice you would offer?

Lawrence Scott: I am going to facilitate a writing workshop quite soon, and I have sent the students two essays by Flannery O’Connor from her collection Mystery and Manners: The Nature and Aim of Fiction and Writing Short Stories. She has lots of valuable advice in those essays, but I like to quote her particularly on the importance of writing from the senses. And also when she says, “Fiction is an art that calls for the strictest sense of the real—whether the writer is writing a naturalistic story or a fantasy.” Also, I like to emphasize, that writing is re-writing, something inexperienced writers forget.