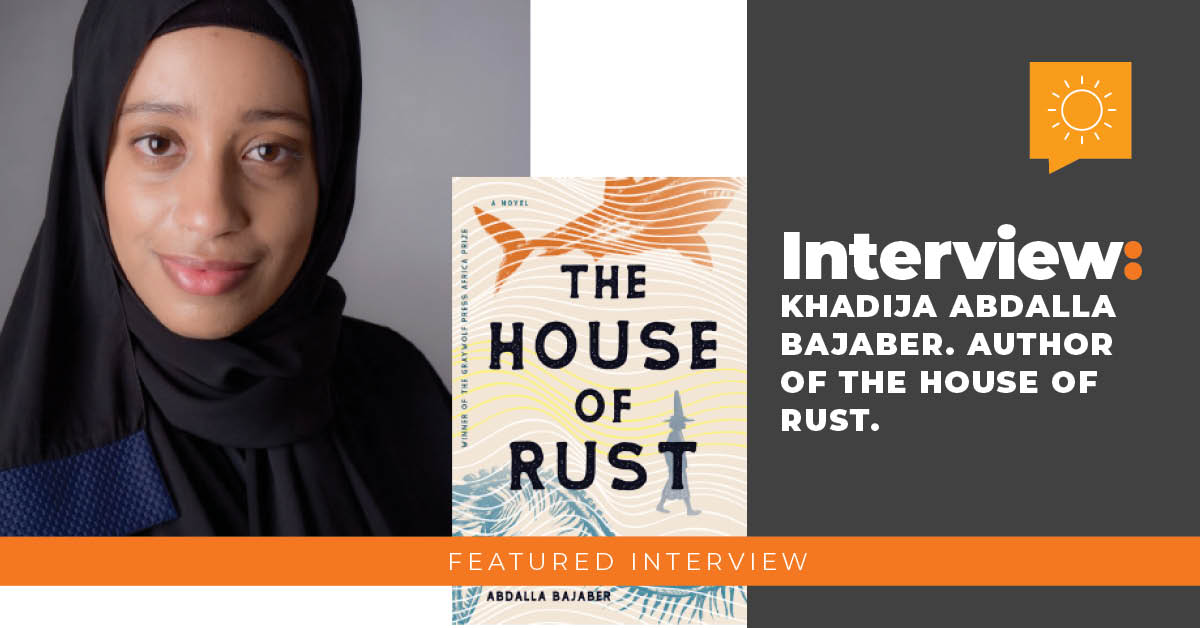

By Gabrielle Guerra

Tell us a little about yourself.

KAB: Both my sister and I are named for our grandmothers. The last grand oath I made was about the octopus. I will eat the octopus, I will not prepare the octopus. I have a temper, so I never get angry. Please never wish me a happy birthday. I don’t know how to ride a bicycle. I like to think I am a pacifist, or I think it in hopes of liking it. It’s not been a full success. Forgetful but unforgiving, unfortunately. Because I am dog hearted, the cat suits me best. What doesn’t kill you will devote itself to a second attempt. I have the dubious honour of being the family’s thesaurus. If a dish is lacking, salt or sugar will nearly always improve it. I am still deeply resentful that the OA got cancelled.

How and why did you become an author?

KAB: About being an author. Prose was frustrating me badly – I’d decided I would be a poet on the side and that my real calling was editing. I wanted to become an editor – but I was going through a lot, I felt like I’d given up on myself. I needed to start something I could finish. I made a point of writing The House of Rust every day, I’d have gone crazy otherwise. It was this love letter I suppose, to the things I thought were trying to kill me. I wrote, and wrote– I set it aside when I got a job. Heard about the Graywolf African Fiction Prize deadline maybe a year later, went type typing, things just came together. It’s luck and opportunity, placement and chance. That’s how it happened. Because I needed to believe I could finish something.

But the noble answer, yes? I’m a writer. Writing can be joyful, it can make you understand, it can give you courage. I write to understand and to pin in place those things that are very dear to me, that I know I will lose otherwise. I remember interrupting Steve Woodward, my editor, during one of the first Graywolf skype meetings we had with everyone – he was talking about the book and I said, “I’m sorry to interrupt you, but it’s crazy to me that you just said ‘Hababa’.” They were confused for a moment by that abruptness, but I think they could see how it hit me all of a sudden, hearing our word for grandmother being read aloud. I’d never read it in literature, let alone heard someone outside of my community say the word. The things I went hunting for as a kid so desperately are worth preserving for kids who come later. I’m willing to see this book out there, even if I get it wrong, even if the one who finds me curses me. I’m protecting what I can understand.

Which authors or other influences do you have in your life?

KAB: The bulk of my reading started and mostly ended with the school library, shout out to Miss Molu! She’ll tell you that that’s where I lived! Some writing exercises advise you try to mimic style – I would do those exercises as a teen, write my detention essays in the style of Catch 22 and other such silliness. But it never stuck, it was always a game, it wasn’t worth sustaining. But no, I can’t say that they’ve influenced me stylistically, or inspired my writing methods – I’ve got enough certainty and pride to say that. What those books taught me was possibility, about communicating deeply, about feeling strongly. What life or love or beauty can mean. They helped me feel strongly about the things I believed made me. Books like that make material and real what might have only been a ghost of a feeling. I’m a big fan of books that know how to create a certain mood. So there are books I’ve enjoyed of course but my real influences are what I’ve experienced of my community and culture, manners, monsters – the long, drawling way of writing, the way of going on and on. It’s not in Kiswahili but it has its rhythm, the rhythm of home. I always sound like myself. The things I write in English aren’t necessarily correct, they cannot be understood the English way. You have to be more open otherwise you’ll misunderstand me. I didn’t pursue the classics when it came to reading, so they never inspired my work. There was a long period when I wasn’t reading at all, but I’d practice and practice writing. I always sound like me. I like to think it might change with each story, so I don’t become too set into myself. It’s trickier trying not to change. But it’s always me.

More than King Kong or Godzilla or anything, Shadow of the Collosus was great at making me realize the wonder of the monster. Huge monsters. Wise and wild. The Fall by Tarsem Singh – where you’ve got story within a story, where everything was so beautiful and imaginative, I was moved by that too. The idea of vastness. I wouldn’t say these pieces of media influenced the story, I didn’t think of them when I was writing it, but I will always remember the feeling of wonder, of going along for the ride wherever it took you, you went with it willingly. Wonder and terror create an odd kind of peace, so media like that have definitely woken me up to what can be possible, what you can visualize, what you can feel. It’s not always literature, but it made a hell of an impression.

How did you come up with the concept for The House of Rust?

KAB: I have a poem called Hājar and the House of Rust over at Enkare Review. They’re the same place. It’s a little early to be going too deeply into what I did or did not mean with the concept, I’m willing to discuss it more once the book has been read by a few more people – perhaps even then I’ll say less. But as briefly as I can; I like the idea of it being thought of as a metaphor or a trick, of it being an actual place being doubted as real. The truth is that it doesn’t matter if it’s physically real, if it’s something you can touch. As cheesy as it sounds it’s not the destination. The idea of rust meshes well with the idea of Mombasa, you’ve always got to take care of the grilled windows. The idea of Aisha’s mother – how metal sits close to the sea, sits still, is eaten away, its gets all red and dry and dusty and sharp – it’s ungalvanized. The rot of it is dangerous, as soon as it gets in your blood it’s curtains. It’s sea things, yeah? There are different kinds of courage, one of them is waking up.

I really enjoyed the family dynamics of your novel. Is this typical of most family relationships in Kenya?

KAB: Thank you, family is very important. It can have its challenges, family isn’t the stone around your neck, it’s your strength. I don’t know about the whole of Kenya, or even the whole of Mombasa, but I know enough to know I’d be lost without my family.

If you’re lucky all your relatives and elders are alive, but most of the time there’s always someone missing. A parent, a grandparent, an uncle, an aunt, cousins – we’re big families, we’ve got a lot of people to lose. We have to accept we could lose each other at any moment. We have weddings as often as we have funerals, all the characters have someone missing from their lives. My parents both lost their mothers at a young age. I don’t know what a typical family structure looks like, but there’s always someone missing – I’m lucky my grandfathers were around. That I had them for as long as I did. There’s always someone missing, we remember them whichever way we can. Being good to your family isn’t about appearances, it’s about love, it’s what you owe each other, what you owe God. Family always wants the best for you, it’s a blessing to still have your elders to guide you. We’re growing older, we’re losing our elders. I didn’t have a Hababa Swafiya for that elderly female guidance, but I’ve had an army of aunts I love. It can be very rowdy, elders can punish and they can mediate, they can be peacemakers or make very big war, they can coddle and they can push, most of all they love. It can be very noisy and lively, clumsy and awkward, aggravating and forceful – but they guide. Everyone steps up to make sure they nurture that love even when knowing loss. I really wanted Aisha’s family to be lively and animated, to be rather fiercely involved in her life. Aisha is only able to grow by letting her family love her.

The House of Rust reminds me a bit of The Odyssey and The Iliad with the main character, Aisha, going on an epic journey to find her father, and she encounters a lot of monsters and special creatures along the way. Did you use mythologies, folklore, or legends from ancient Greek or other cultures for inspiration?

KAB: Ah, that’s interesting, and very classic! My knowledge of classical Greece is very limited but I do like the warnings about how even now the nymphs will swim up to boats and tearfully ask for news of Iskander, and if you love to live you must tell them that Iskander is doing very well, that he is in excellent health – otherwise they’ll sink you and kill you in their grief. Alexander is a bit younger than the epics, that’s as Greek as it gets with me.

But I’ve always loved monsters, I like legends, myths – I like experiencing terror in a controlled and safe setting, horror movies are great for that. Ghosts are very boring though, I can’t take ghosts seriously. In the comp lab other kids would be constructing their Facebook profiles, I’d be on the internet reading about mythical beasts – I could do that for hours. The monster is only as interesting if the culture believes in it, if it’s taken seriously. Which means I reached for Japan, Vietnam, Egypt and South America, and of course Africa and the Middle East whenever I could find it. Western monsters lack that important element personally, whether it’s because it’s lost to time or pagan traditions fading away. People tell the horror stories to amuse themselves, but there’s no belief, that real terror – that air of whispering something dangerous in a daring place, it’s not there with Western monsters. Or at least that’s how I’ve experienced it. If they’re not real to the people who’re meant to fear them, they cannot come alive enough for me.

I made most of the monsters up. There’s real monsters mentioned in passing such as Nunda, Eater of Men and hooved buibui woman, but I avoid going into detail. There’s figures and mythologies I want to explore in future, like the kingmaking gazelle or Liongo Fuma. Every culture has some kind of sea monster. I drew on the culture here to create my own. When I was writing it they were very clear in my mind, I didn’t hesitate or stop to draw up options for the monsters. I knew the first monster was a long serpent, big eyed, sleek and grating, failed courtier type – the second was a hoarder of ships, a voice-stealing sea-grave, selfish, perhaps the cruelest of all of them. The third is pale like the mjiskafiri, curved like a hook, enormous, rotting, shark king, a devourer. They jumped to my mind almost fully formed. I told it linear, each time I met a monster, there they were immediately, whole. Even their stories, their reasons for being, all their grandstanding – it came so quickly to me. Grandstanding and lengthy storytelling is very Mombasa, very Coast.

The monsters highlight Aisha’s anxieties, prod at her fears, make fun of her and make light of her. She changes her approach and adapts, until she settles into herself and finds her true voice. They don’t let Aisha pretend without punishing her pretence. They all serve their purposes, it’s important that the second half of the retrieval mission gave her a second meeting with the first two monsters, to highlight what changed and what was at risk of staying the same. They are all Coastal in heart. In what they represent. The dreads, the fears, the anxieties they stir up. What they consider courteous, what they believe to be rude. What they think they’re owed. The manners they do or do not have, it’s all Swahili. Then you have characters like Almassi who are more obviously based off the cultural touches of Mombasa and its multitudes of cultures – it shows in his dress, the hat is traditionally worn by the shepherdesses of Hadhramawt, the bougainvillea to me is the bloom of Mombasa – Yasmini and vilua are all well and good, but it is bougainvillea that makes my heart very fierce. The kikoi, the sandals, the black piko that splits his throat. Dressed like the old men who play karata down in town, where my own mother’s father used to play cards. I liked being able to bring all these elements together to create this Swahili prince of monsters who likes sweet things and is rather haughty, petty and somewhat mildly irresponsible. The style, the taste, the mood, it’s homegrown – that’s my home. So, the monsters are mine – or ours, they are indisputably Coast.

.You used a cat as Aisha’s guide for her journey. Birds are also prominent in your novel. Do these animals have significance from your upbringing?

KAB: What is Mombasa without its stray cats and rowdy crows? You find them everywhere. The crows wake you up more noisily and quarelssome than any cockerel, I love how they gather and gossip, how they fight and hold grudges. Cats are always slinking around the corner, inviting themselves into restaurants and kitchens and homes. They don’t have homes of their own, the whole world is their home. Cats and crows, they’ve got a long memory, they keep the sharpest grudges. Both steal and scavenge, both are beyond domestication, both belong very fiercely to their own natures and will not share their counsel with us. The stray cat is too wild to forget where it comes from, perhaps after a long courtship it will sit nicely in your house and let you give it milk, but it will leave when it wants to leave – no one will govern its comings and goings, the stray cat. The stray cat can be a solitary creature, but the crow – a crow without a clan cannot survive, the crow must have a family. Both cat and crow are nomadic, they go where they must go. Both have in their nature a particular mischief and a particular cunning. I have been a friend or an ally to both cats and crows, who you must know, hate each other. My dealings with crows feel like a fever dream trying to explain. My dealings with the stray cats, that is too precious to me to share. They owe us absolutely nothing so beautifully. I love it the crows they’re out there causing a ruckus and being irritating as hell, it lets me know where I am and my place in the world. The cats yowling in the night. That’s Mombasa kelele, which is the best kelele.

There is a lot of responsibility and pressure put on Aisha for being a young girl. Is that common for children in Kenya or Africa to have a lot of responsibility at a young age?

KAB: How strange, I don’t see it as a great deal of responsibility. There’s honour in the work Aisha does, they’re normal responsibilities – it’s a joy to be of service to your family and community. In fact, Aisha has it easier than other girls of that time – she only has to take care of her grandmother and her father, who take care of her. My mother is impressed that Aisha makes such fine kaimati, she jokes that she wishes I was half the help around the house that Aisha is! The chances of that happening are low.

Aisha has added pressure because her grandmother (Hababa Swafiya’s sister), had a child out of wedlock – Aisha’s mother Shida, so in terms of prospects for her future such as marrying well and having a good name, Aisha has the cards stacked against her. She can’t just be good, she has to be perfect. You live in a house, you do your best to help out, not to earn your keep but because you want to take care of the people you love. Aisha has a lot of chores maybe, but she takes comfort in them, she even escapes into them – they’re a sanctuary, they’re a way of hiding. Until she can’t hide anymore. Aisha has enough freedom to go running around Mombasa, and despite the scandal of her mother’s birth and despite Hababa guiding her towards being a good woman, Hababa doesn’t punish Aisha for her oddness the way you’d expect someone else to. She wants to make sure that Aisha is happy, but Aisha can’t be happy because she doesn’t know what she wants and she has a tough time communicating it when she does understand a little of it. Hababa Swafiya has to do all this guesswork and try really hard to keep the family afloat and make sure Aisha grows up to be a good person, a person with no regrets. Everyone in the family struggles with shame, shame for not being enough, shame for failing, shame for choosing wrong, for not acting – Hababa Swafiya, Ali, even Zubeir. There’s pressure which might make some of them disappear into their work. The circumstances are unfair, the pressure is unfair, but the actual work is honest and worthy. Not something to be pitied.

Why is reading international/global works of writing important?

KAB: Reading ‘global’ means running the chance of having to look yourself in the face, confronting yourself in a way maybe the books you’ve gotten used to

won’t let you, the books in which you’re the standard, books in which you’re comfortable. Regardless of whether literature is ‘global’ as a reader you have to come to understand who the intended audience is, the reader thus manages their expectations on whatever they imagine they might be entitled to. Being able to read books from different parts of the world, and knowing your place in that audience, and your place in the history the story is drawing from, takes a lot of intelligence and awareness, and it’s a way of exercising that, especially if you’ve gotten very comfortable with a reality where you’ve always had access, you’ve always been centered, you’ve always been the standard and you’ve never had to wonder what not being it is like. I didn’t write the book because I wanted to prove that diverse literature is important, to prove anything to anybody. Did I write my book to educate? No. Is my audience a neutral, raceless, faceless audience? No. It doesn’t mean I hate you or that you can’t enjoy or shouldn’t enjoy my work. I’m letting you into my house, take off your shoes. Some things might be familiar or unfamiliar, you might not like it at first, maybe not at all. The reader must adjust their palate, developing it is not my problem and it certainly isn’t my purpose.

The past few years have been especially hard for the world. We’ve gone through a lot of heavy things recently. Do you think people will or are reading more books that are different from their culture to help understand the world we live in a bit better?

KAB: I don’t know the data, I won’t speculate. Whoever has managed everything enough to continue to find enrichment in reading and in writing, that’s wonderful – it’s not been that way for me. I know when times were tough for me before the pandemic my go to was always fiction that didn’t take itself too seriously.

I think people have had to be by themselves, because of quarantine – at home, if they’re alone or they’re with family, you really end up re-evaluating everything about work and life. Sometimes you clutch at the familiar and normal, sometimes you explore – I noticed it happening a lot with food, I’m not sure I can say for certain that I’ve observed it with books. I don’t have the data for either.

I hope it’s not been terrible for you. Staying at home hasn’t always meant rest. It’s not been an extended vacation, it’s been house arrest and anxiety. In the beginning of the pandemic when we thought this would all blow over it was nice to have the family together in one house, and you’d have all these plans to do things that you didn’t get to do before. I’d been home for a while before it started. Then people started dying, kept dying, funerals, worry – how could anyone relax enough to read then? I did more reading before the pandemic than I did during. I’ve been distracted, I’ve been worried sick. I’ve had plans to read, I’ve spoken them before, but it’s been hard as hell to do it. I’m staring at a whole shelf of books I got recently, they’re meant to help me escape, they’re meant to help me read my way into being a better writer. I’ve read very little of them. I’m healthy, I’m safe, I’m blessed and privileged to be so – but I’m not rested enough, at peace enough, to escape so easily. I get so deep in my worry for my loved ones, I get so deep in myself. In some ways we are too fixed in this place, the danger isn’t over. I recently left home, I’m somewhere where I’m meant to have time to do more writing – but I find myself missing my family, I find myself distracted in the same exact ways, worried in the same ways. It’s hard but I make sure to be grateful, I know it can always be worse.

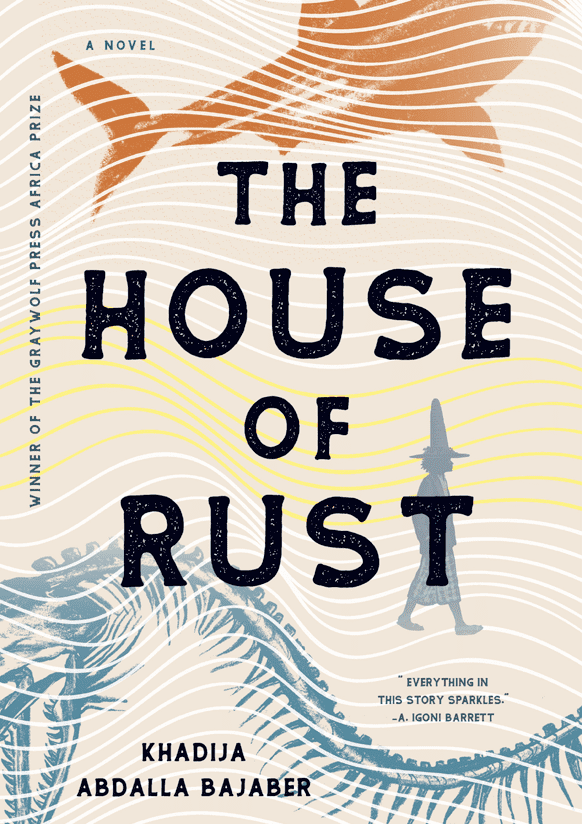

About the Book:

The House of Rust is an enchanting novel about a Hadrami girl in Mombasa. When her fisherman father goes missing. Aisha takes to the sea on a magical boat made of a skeleton to rescue him. She is guided by a talking scholar’s cat (and soon crows, goats, and other animals all have their say, too). On this journey Aisha meets three terrifying sea monsters. After she survives a final confrontation with Baba wa Papa, the father of all sharks, she rescues her own father, and hopes that life will return to normal. But at home, things only grow stranger.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October / November 2021 Issue: Read Global.