Shelf Unbound: You’re a highly successful Hollywood entertainment attorney, and you won a Tony for co-producing Book of Mormon. Why add writing to the mix at this point in your career?

Kevin Morris: I’ve always wanted to write fiction, but have come to it the long way. When I graduated from college, 30 years ago, I made a conscious choice to go to law school to earn a living. I promised myself I would eventually return to writing fiction. Good fortune led me to Los Angeles, and entertainment law and producing have been a terrific way to practice and stay involved with art and the creative process. Though I’ve written non-fiction—articles, book reviews, opinion pieces—finally the time came where I decided I had to dedicate myself to telling stories. That’s what I have been doing for the past five years, at least two full days a week, and beyond that as much as time, representing my clients, and being a dad will permit.

Shelf Unbound: Your father was a refinery worker, and a theme in some of these stories is respect for the capable doers of your parents’ generation compared with today’s high-tech button pushers. In “Summer Farmer,” a depressed wealthy movie producer talks about riding the service elevator with “the working guys, the electricians, caulkers, framers and the like. Seeing them made him think of his dad and his uncles, who carried pressure gauges and tape measures and had specks of drywall in the hairs of their forearms at the end of the day.” In “Mulligans Travels,” Jim Mulligan—50 and struggling to make his next big tech deal— accidentally runs over his dog, which then becomes wedged under the rear axle, and Jim struggles ineptly to get the jack to work in time to save him. Are you nostalgic for pre-tech times and a real hard day’s work?

Morris: Not so much. It’s more that I am interested in the American Dream as it exists in today’s world and the relationship that men have with success.

The way we live is changing rapidly and success is constantly shape-shifting. We’re busy trying to define it, deal with it, not get jealous about others who have it, what have you. And when we think we have achieved it, we worry that we are deluded or have redefined success just to make ourselves happy. At least the people and characters who interest me do. Stridently successful people without any doubt are pretty one-dimensional.

There’s also a technical reason for upper mobility in the characters. Taking someone from poor to rich is a useful vehicle—it adds a layer of alienation and complication to a person’s story. We chase money so much in American life that we risk looking up only after it is too late. I’m hardly the first to observe that. And the over-achievers are especially prone to it.

But, I’m more interested in the pressure not to let life pass you by before it passes you by, and the conundrum that puts my characters in. That’s Jim Mulligan and Eliot Stevens and John Collier from “Rain Comes Down,” even though it’s now too late for him. Is that a white man’s problem exclusively? In some ways, but mainly I think it’s a modern human problem.

Shelf Unbound: Many of your characters, despite being privileged, are in a mid-life malaise—depressed, divorced, dissatisfied. You recently turned 50 (as did I)—is there an autobiographical element in these stories?

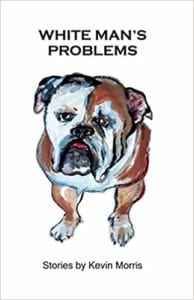

Morris: It’s not on-the-nose autobiographical. More a sense of memory and an attempt to make something creative out of my life experience. The guys I write about share a sort of alienation as they get older. They’ve been hard workers and “succeeded” by society’s standards, but they can’t help feeling like they should be happier. So, like Henry, the dog on the cover, you can’t tell if the characters are tough and ready to fight, or about to be run over. (The sadness in Henry’s eyes may be a hint.)

Shelf Unbound: A rare exuberant moment in these stories is in “The Plot to Hold Hands with Elizabeth Tremblay,” which ends with high school student Roman Budding having indeed just held hands with Liz: “I think about her sweater and her lips. I still smell her. I start to run. Slowly at first, kind of a home-run trot. Then I go faster. Then faster still. All the way home.” Do you think that kind of unfettered exuberance is only for the young?

Morris: They sure seem to be able to access it more easily. When we’re young we’re so hyper aware of ourselves—self-conscious, but also much more willing to take chances and live on the edge. It’s easier for the young to feel unfettered because they are unfettered. They don’t have to worry about failing their boss or their family. They don’t have to worry about the responsibilities and fears that come with being a grown-up, a parent, a spouse.

Shelf Unbound: You self-published White Man’s Problems in 2014, and then it was picked up by Grove/Atlantic. Why did you initially choose to self-publish?

Morris: The first book I wrote, a novel, received good feedback in terms of its literary merits but editors thought it was too hard to categorize so, ultimately, I couldn’t find a traditional publisher. It was discouraging but I continued to write. I found myself writing stories, and after a year had a collection of nine that I thought would make a good book. I didn’t even consider submitting it to a publisher, knowing how difficult it is to publish story collections. I knew digital publishing was becoming easier and self-publishing more acceptable so I decided to go for it.