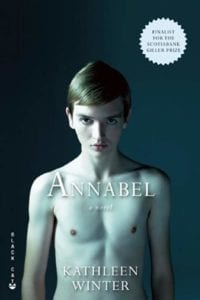

Shelf Unbound: Annabel, your first novel, was a best-seller in Canada and a finalist for the Giller prize. It won the GLBTQ Indie Lit Award and has just been named a finalist for Amazon.ca’s First Novel Award. Annabel is the story of an intersex baby born in Labrador in 1968. How did the idea for this story come to you?

Kathleen Winter: An acquaintance told me in my kitchen about an intersex child. I’d never heard of this, and did some research. I gradually found out many, many children are born with ambiguous gender, and I wanted to write about this.

Shelf: Would you give us a brief description of the four main characters?

Winter: Wayne/Annabel is the intersex child. Treadway is his hunter/trapper dad, well-meaning and loving, but traditional. Jacinta is Wayne’s mother—a dreamer, a city girl trapped in the wilderness. Thomasina is Wayne’s midwife, mentor—a strong woman role.

Shelf: And the setting could be called a character as well. Describe Labrador and why you chose it.

Winter: Labrador is magnetic, northern wilderness: alluring and brutal, mystical and merciless.

Shelf: In the prologue you describe a white caribou who has left its herd. “Why would any of us break from the herd?” This sets up a major theme of the novel, the many ways people can be isolated. Do you see Wayne as the most isolated character in the book?

Winter: I love this question about Wayne’s isolation. I see his isolation as having an end, as he connects with the world. I see his mother as being perhaps the most isolated in the book, because she loses so much and can’t confide. Jacinta is cut off from any truth, or friend, or solace that might have nourished her.

Shelf: I actually think that his father, Treadway, is the most isolated. You render him quit beautifully. He does harsh things but in private reveals uncertainty. In the woods he sees a vision of his daughter and loves her. Was it hard to find his tenderness?

Winter: I didn’t know his tenderness existed before I wrote the book. He showed it to me himself. I waited and he showed me. That’s how I do a lot of writing, by waiting to see what would really happen, not what I think should happen.

Shelf: The mother, Jacinta, refers to the baby as a girl at the doctor’s. Does she always think of Wayne as a girl?

Winter: Yes, Jacinta always sees the girl, Annabel. She sees Wayne as well, but she secretly and longingly sees her daughter.

Shelf: Do you think it could be argued that Treadway’s decision to raise the child as a boy was not entirely wrong? Would Wayne have struggled equally raised as a girl?

Winter: For me, the other choices include raising the child as ambiguous, without denying the male or female aspect, so to answer your question, I don’t think it would have been any easier to deny the Wayne side of Wayne and honour only Annabel.

Shelf: You mention waiting to see what would happen in your stories. What else in the book came to you from waiting?

Winter: Bridges. The bridge in the novel used to be a tree house but I didn’t like it. I waited and waited, and one day bridges floated to me. Also the ending—that was the hardest part and I had to rewrite the final third of the book many, many times.

Shelf: I was particularly struck by the bridges metaphor when I re-read the book. It is subtle but powerful. All of the characters seem to

be attempting to bridge two worlds or wishing they were in another world. Thomasina, the mother’s friend who witnesses the birth, seems to most successfully break out of her restriction. Tell us more about her.

Winter: Thomasina is the strong one because she sees nothing wrong with blunt truth. She’s wise and strong, though wounded.

Shelf: The story takes place in 1968. Why did you set it then, and would it play out the same today?

Winter: I thought Medicine would have been less evolved then, but in fact the same brutal choices are made today.

Shelf: Isolation is a big theme. The place is isolated, the characters are isolated from one another. Did you intend that at the start?

Winter: My favorite author is E.M. Forster, who wrote “only connect.” Isolation is a huge theme for me, yes. My whole aim of writing is, I sometimes think, to ward off loneliness. I mean my own loneliness, the loneliness of the people in my novel or stories, and the loneliness of being human.

Shelf: You mentioned struggling with the ending. How did you settle on this particular one? What alternatives did you consider?

Winter: God, the possible endings! Treadway wreaks revenge on Derek Warford. Jacinta ends up in the mental hospital. Wayne and Wally become lovers. Wayne marries Graycie Watts. Wayne stays in Labrador and becomes an outfitter. I could go on all night with possible endings.

Shelf: So it sounds like you wanted to give Wayne happiness.

Winter: I had to give Wayne a chance of happiness because the real lives of intersex people contain so much trauma. I couldn’t bear to write a novel without some hope for Wayne/Annabel. Not a happy ending, but one with a hope of connection.

Shelf: You’ve mentioned E.M. Forster—what other writers do you most love and respect?

Winter: Heinrich Boll, Colm Toibin, Katherine Mansfield, Gretel Erlich.

Shelf: So what are you working on now?

Winter: I’ve nearly finished a murder mystery and am doing preliminary reading for a nonfiction work about the Arctic.

Read an Excerpt:

Featured in August/September 2015 Issue

Treadway persisted. “Baby’s healthy?” Jacinta knew he never spoke idly, and he was not speaking idly now, and he was asking her for an honest answer. But what was the most honest answer?

“Yes.” She tried this in a normal voice but it came out as a whisper. The strength of her voice, her real tone, which was a tone of plainness, like rain, which Treadway loved but had not told her he loved, did not inhabit the whisper. She wished she could go back and say yes again. Heat still radiated from Treadway’s hand deep into her belly.

“He’s a big baby,” Treadway said, and the heat stopped.

Jacinta wanted to blurt, “Why do you say he? Are you waiting for me to confess?” But she did not. She said yes, louder than normal this time because she did not want another whisper to betray her. Her yes was a shout in their quiet room. Their bedroom was always quiet. Treadway liked a place of repose, a tranquil sleep with a white bedspread and no radio music or clutter, and so did she. She lay there waiting for his hand to heat her belly again, but it did not. Had he moved it away consciously? Treadway was a man whose warmth always heated her unless an argument stood between them.

In the morning Jacinta told Thomasina, “I went stiff as a hare. What are we going to do?”

Any time fortune came to Thomasina—acceptance of her grass baskets by the crafts commission, the flowering of a Persian rose in this zone where no one could grow any rose, not even the hardy John Cabot climber—she knew happiness was only one side of the coin and the coin was forever turning. She had been single until she was well past thirty, when Graham Montague had told her he didn’t care that she had a curved spine and felt old—he wanted to marry her if she would marry him. Annabel had been born the following year and Thomasina had every reason to be happy, but instead she held her heart at the same level she had always held it, because she did not like extremes of feeling. Now she told Jacinta, as they spread jam on toast thinly, the way they both liked it, so gold shone through, “We will love this baby of yours and Treadway’s exactly like it was born.”

“Will other people love it?”

“That baby is all right the way it is. There’s enough room in this world.”

This was how Thomasina saw it, and it was what Jacinta needed to hear.

From Annabel by Kathleen Winter, Black Cat 2010, www.groveatlantic.com. Reprinted with permission. All