John F. Blair, Publisher

www.blairpub.com

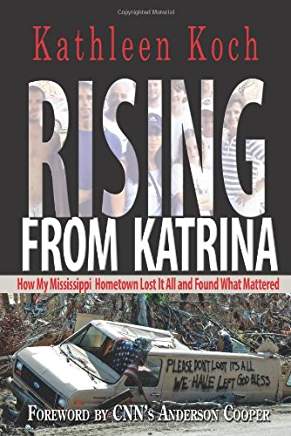

In her account of the surreal experience of reporting on the all-but-complete destruction of her hometown of Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, former CNN reporter Kathleen Koch gives what may be the best description of Hurricane Katrina’s impact for those of us lucky enough not to have been caught in its path. By focusing on a single community, Koch brings the initial horror and devastation wrought by the storm—as well as the ongoing and present day (meaning still, right now) struggle to recover—into proper perspective. Rising from Katrina puts a name, a face, and a history on a dozen or so families who survived the event, allowing readers to understand the actual impact of FEMA’s slow response on real people, not just the media portrayal provided by an inept administration appointee whose boss thought he was doing a “heck of a job!”

—Jennifer Wichmann

Shelf Unbound: Personal experience as news seems to be a growing phenomenon in media. As a CNN correspondent covering the flooding from Katrina, you were part of the vanguard of this trend. How do you think such subjective crossovers affects journalism, its mission to deliver news, and the interest that the public has in news?

Kathleen Koch:I ventured with great trepidation into this realm of reporting. I never believed in inserting myself into the story. I often argued against including a standup (me on camera talking straight to the audience) in my reports if I thought it wasn’t warranted. I am a traditionalist and believe the news should be the focus—not the reporter.

But apparently audiences are tiring of “straight news” and want both reporter involvement and opinion. I think the former can be used effectively if the journalist exercises restraint and uses their personal involvement to draw viewers into the story, educate and inform them, and make them care. In cases like mine where a reporter has deep personal ties to and knowledge of an area where a major news event is occurring, then their personal take on a story can give the audience valuable insight. I believe things can go awry when a reporter’s personality and opinion begin to dominate. In that case, the end result can cease to be news and morph into an editorial.

Shelf: On several occasions that you note in the book, remaining an impassive observer in the face of desperate times was incredibly difficult for you, such as when you saw the abandoned convenience store with available food and water. Looking back, do you think you walked the correct line or is there something you would have changed about your experience?

Koch: We walked a very fine line in those days after Katrina, and I think we did the right thing. True, it was frustrating to go back to that convenience store six months after the hurricane and see the food and drinks that were perfectly good right after the storm rotting and covered with swarms of flies. Still, without the owner’s permission, we just couldn’t bring ourselves to go in and haul out armloads of items that weren’t ours. Yes, we did cross the line and get involved. But my crew, producer, and I did it when we were off the air. Yes, we took blankets, clothing, food, and water to victims. But we bought it ourselves when the first store opened up. Yes, we looked for missing people and gave away our own hurricane supplies before we left. But we did it off camera instead of turning our personal desire to help into a self-congratulatory news story. The only thing I wish I could have changed, I couldn’t. And that was to have had more time that first week to locate a missing man before his family found his body three days after we departed.

Shelf: Your accounting of hurricane coverage, particularly following Katrina, seems more akin to active war coverage than weather reporting. Because of your personal experience growing up with the threat of hurricanes you knew the extent of that peril more than most, but it also had to be a somewhat familiar danger. Do you think you would have as easily accepted an assignment in Iraq or Afghanistan as you did in Mississippi in 2005?

Koch: No. As a CNN correspondent, I had the option of taking “war training.” I never did. I believed that would have constituted an implicit agreement that I was willing to accept an assignment in a war zone with bullets flying around me. I had young children. I felt it would be irresponsible to risk my life that way for my job.

The risks faced when covering hurricanes, I thought, were manageable. But none of us had ever dealt with a hurricane like Katrina. Now I understand that the greatest threat may not be from the elements, but from the chaotic and lawless situation you find yourself in afterwards. And I also now understand the mental and emotional toll such circumstances can take. Still, it didn’t stop me from covering Hurricane Gustav in 2008, nor would it dissuade me in the future.

Shelf: Many people turn away from tragedy as a mechanism to cope with the stress and emotions their stark reality engenders. In covering Mississippi after Katrina, you repeatedly turned back to the tragedy you witnessed there instead of ignoring it. Why do you think you made this choice?

Koch: That was home. They needed me. There was no way I could turn my back on them. Mississippians have a long tradition of taking care of their own. Also, the national focus on the tragic levee collapses in New Orleans made me even more determined to keep returning to Mississippi to tell the Gulf Coast’s story and make sure people there got the help they needed. Finally, when my producer and I left the Bay St. Louis citizen’s shelter Saturday after the storm, I told the people there, “I promise I won’t let anyone forget what happened here.” I keep my promises.

Shelf: You and many of the sources you quote remarked on the tendency for Mississippians to look on the bright side of their situation and be grateful for what they had, not dwelling on what was lost. In what ways do you think that attitude played a role in the long wait for relief and lack of recognition that Bay St. Louis and other Mississippi communities experienced?

Koch: It definitely played a role when it came to media attention. Just like the old adage, the squeaky wheel gets the grease, cities where mayors and public officials scream and curse and sign-waving citizens protest angrily in the streets get attention and coverage. Towns where folks work together, say they’re blessed and things will be just fine, don’t. Mississippi’s story was more nuanced and therefore really needed to be told by a native like me or ABC anchor Robin Roberts. You had to understand the people, their history and traditions, and why they were reacting as they were despite being the ground zero of the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

Regarding the long wait for relief, I believe that was simply a matter of poor logistical planning. Affected areas received help as soon as the federal and state governments could get it there. Whether their citizens and leaders screamed for aid or not was not a factor.

Shelf: While covering Hurricane Gustav, you describe driving across a drawbridge in Biloxi and experiencing gale-force winds which almost swept your vehicle off the bridge. I was struck by your shock that some arm of the government had not done something to close the bridge because of the dangers from high winds. How have you maintained your faith in the general ability of government to keep people safe after witnessing first hand the problems that followed Katrina?

Koch: In the case you mention during Hurricane Gustav, I was surprised because a city police car was sitting at the foot of the bridge. The officer had to be aware of the dangerous conditions. I was stunned that the vehicle was not blocking all entry.

In general, I have lost much of my faith in the ability of government to help people following major disasters—particularly the federal government. I tell groups I speak to about crises and disaster preparedness that you will be relying first on those closest to you—family, friends and neighbors, your local government, and help from neighboring states. But anyone who’s expecting the federal government to come riding to the rescue will be sorely disappointed. The feds will get there if and when they can. I also think the local authorities are the ones who best understand the people and their needs. Many found that after Katrina the federal government and some national relief organizations insisted on strict adherence to cumbersome rules instead of taking the speediest route to help the most people.

Shelf: So many of the individuals living in Bay St. Louis have a remarkable love affair with the water. Following Katrina, many seem to have maintained that connection. How do you think they have eluded feeling betrayed by nature?

Koch: I think most people there who love the natural beauty of the place also respect the destructive force of the elements. For generations, so many in the region have made their living off the water and they understand that which sustains you can also destroy you. So that acceptance of the risk is part of living on the water.

I do see a heightened level of concern when storms approach the Gulf. The town of hardy hurricane veterans has a new sense of vulnerability. As I relate in my book, the first heavy thunderstorms after the hurricane caused widespread anxiety and brought back frightening memories for many. Much of that early trauma has faded. And I am relieved that more residents than ever before now evacuate if a real hurricane threat materializes.

Shelf: At the end of your book, you relate how so many of those who survived the hurricane have begun to focus on smaller, more meaningful things in their lives—nights home with family instead of shopping at the mall for example. How has your experience with Katrina and its aftermath shaped the values that you live by?

Koch: I take any opportunity I can now to volunteer, and encourage my family to do the same. I’ve always been frugal and not terribly materialistic, but now I loath waste and conspicuous consumption. (I can’t help thinking how money and energy could be put to so much better use on the Gulf Coast or in Haiti, etc.) I have greater faith in the ability of the individual to make a difference. I have a deeper faith and trust in God. Finally, I have a greater appreciation of the brevity and fragility of life and the need to reach out every day and build bridges not walls to connect to others and make this world a better place.