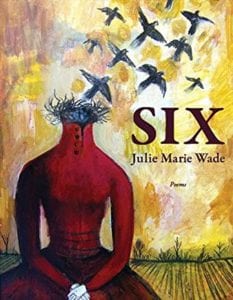

Six poems from the Lambda-award winning author of Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures and When I Was Straight

Red Hen Press

Shelf Unbound: You have six poems with six points of view. Why choose this structure and why six?

Julie Marie Wade: Oh, I’m so glad you asked! Years ago, in the fall of 2002, I took a graduate seminar at Western Washington University with the poet Bruce Beasley, who has also graciously blurbed this collection, SIX. What I remember vividly is Bruce telling us in class one day, “You only write about six things your whole life.” What I don’t recall now is whether he was passing on received wisdom from another poet, a mentor of his own perhaps, or whether Bruce himself determined this truth and this number. I wrote in my notebook “SIX THINGS” and underlined the phrase. It felt important, even oracular—something I would return to someday. The context for Bruce’s statement was that people are driven by relatively constant and enduring obsessions. We don’t always choose our content or even consciously change our content; often, our content chooses us, and it abides with us regardless of our intentions. Bruce was advocating for all the young poets in the room to concentrate on form, to explore the ways we could innovate with structure in order to keep our content fresh and in order to probe our resident questions and obsessions more fully, for both ourselves and our readers.

After I graduated from the Master’s program at Western, I went on to an MFA program at the University of Pittsburgh. Officially, I was working on a poetry thesis called Postage Due: Poems & Prose Poems, which would one day become my first published full-length collection of poems. But unofficially and semi-secretly, I was working on the project I referred to as my “shadow thesis,” the project that would become SIX. I asked myself, “What are my six things?” What resident topics or themes or points of inquiry guide everything I undertake to write? In seeking to answer that question, I wrote six long poems, each reckoning with one side of my personal hexagon of obsessions. A reader might find any number of resident themes in this book, but I think I am writing about art, language, sexuality, vocation, religion, and love. Of course I had to write my way through these poems in order to be sure.

Shelf Unbound: I’m reading your lesbian narrator’s line “Does it really matter that no one understands who we are?” just a few days after the Orlando massacre of 49 gay and lesbian people and it is really resonating with me. What’s your answer to the narrator’s question?

Wade: I’m reading your question now at that same pained moment in our nation’s history in June 2016, and I’m thinking back eleven years to when I was writing the poem “Layover” in which the line you referenced appears. It is the second poem in the collection but the first poem I wrote as the book was beginning to take shape. At that time, in 2005, my partner and I were struggling to find a clear and unmistakable lexicon to describe our relationship. We had moved in 2003 from a liberal college town in the Pacific Northwest all the way across the country to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a city in a state where we knew no one. Back in Bellingham, when Angie and I referred to each other as “partners,” people knew immediately what we meant. Life-partner. Domestic partner. Many of the heterosexual couples in that community referred to their significant others, even their different-sex spouses, as partners. But in Pittsburgh, at least at that particular cultural moment, people kept misunderstanding what we were saying. They thought we meant business partner or exercise partner or some other kind of partner that was not only platonic but potentially replaceable, expendable. It was frustrating trying to communicate that I wasn’t “single” in a world that insisted people were only “single” or “married,” particularly during a time when marriage for people like me seemed unlikely to most and incomprehensible to many.

I’ve been haunted by this question for years: Does it matter that no one understands who we are? I see now that it isn’t just a practical question of making the person in front of you understand that the person beside you is your true love, your partner in all things. It’s also an ideological question that queer people in this culture are constantly colliding with. We see ourselves depicted more and more often, but are we represented fully, represented well? Are we given the complexity of heterosexual characters in literature and film, the time and attention allotted to heterosexual people in the public space? On that front, I would say we have a long way to go before we are understood deeply by our culture—before we move beyond stereotypes, tropes, supporting roles, the punch lines of other people’s jokes. And in the brutal case of the recent Orlando massacre, it matters tremendously that so many people are reluctant to name the dead as members of the LGBT community. My friend, the poet James Allen Hall, talks about the dangers of “inning.” Even when queer people are trying their best to be out in this world, they are often pushed back in, subsumed into the dominant heterosexual culture. I couldn’t agree with James more, and nothing makes me feel more helpless or more inflamed. When queer people talk about the nuances of our lives, we often face accusations of “flaunting.” Sometimes, when we talk about our lives at all—especially when we acknowledge the partnerships we have made with others of the same sex—we are accused of being “political,” as if that’s a bad thing, as if we should just simmer down and stop mentioning our identities and our relationships so that certain others won’t be offended or made to feel uncomfortable. But I still believe the personal is political, and I want to write always from the point of view that no one is likely to break the silences around my life and identity but me. If I want to be understood at all, and particularly as a gay woman in this culture, I have learned that I need to make the first move, and that first move for me is always through poems.

Shelf Unbound: In one poem, a lesbian looks out the window of her new home at the family across the street, a straight couple with three children, wondering about their lives and worrying what they will think of hers. How do you go about constructing a scene like this in your poetry?

Wade: Well, you know, at the time I was working on that poem—the poem called “Layover,” the poem that inaugurated the collection for me—I was also thinking a lot about a class I had taken at Pitt on projective verse. In simplest terms, projective verse poetry focuses more on generation than revision, with the poet allowing the world into her poems in very immediate ways. So I had been mulling a lot on my six things, and then I knew my partner Angie was going out of town for the weekend visiting her sister in Atlanta. I knew I was going to be lonely, missing her, and I wanted to channel that loneliness into a poem that looked more broadly at other ways I feel isolated. The limits of language are a major part of that isolation. When most people most of the time presume you are heterosexual, it can be difficult to strike up even the most basic kinds of conversations. There’s always the challenge of finding the right time and way to disclose your identity, knowing that most often another identity, an incorrect identity, has already been presumed. In the spirit of projective verse, then, I decided I was going to write the whole poem over that one weekend and that I was going to let whatever happened outside my window come into the poem. I was going to welcome distractions and not treat them as such. I was going to use the immediate vicinity to help me explore my larger questions. And it just so happened that our neighbors were having a birthday party for one of their children. I didn’t know those neighbors—we had never me—but it was almost impossible to go into our kitchen without seeing them, since our backyards were adjacent to each other. The neighbors were foil characters of Angie and me, in a sense—a heterosexual family with children, juxtaposed alongside a homosexual family without children. And the more I noticed the neighbors, the more I really paid attention to them, the more I realized that they were part of this story, too. They were already the face of a family to most people—no one would have any trouble recognizing them as husband and wife or as parents—and so they had a visibility I craved—maybe a visibility I also envied—but I also knew I didn’t want their life. It wouldn’t have been the right life for me. So much of my reckoning in that poem happened because I kept looking out the window and seeing them and going through a gamut of feelings about them, from anger to envy to pity to empathy to compassion—but also seeing my own reflection in the glass as a kind of visible, palpable point of contrast. We lived in the same neighborhood, in houses that were relatively identical, and we were probably roughly the same age, and yet, our experiences of the world were so different.

Shelf Unbound: Throughout these poems are thoughts and questions about identity and being “other.” What interests you in exploring these themes?

Wade: Everyone is an other in some way, and I think when we become aware of the way(s) in which we are other, and when we begin to explore those ways, whether through a particular creative process or through reflecting upon our lives at large, something paradoxical happens: We discover more of what we have in common with other people. We become more aware of various aspects of our shared humanity. My friend, the poet Stacey Waite, cites a Japanese proverb in her stunning book, Butch Geography: “The reverse side also has a reverse side.” I think that second reverse side brings us back to what we share with others—love, hope, fear, longing. We feel separate, different, isolated, but if we learn how to fold again, we discover places of overlap. When I finished my MFA at Pitt in 2006, I also completed a graduate certificate in women’s studies, and the only teaching work I could find initially after graduation was as an adjunct professor of women’s studies at Carlow University. I loved teaching those classes as much as I loved taking classes in the field as a graduate student, and I was particularly drawn to the concept of intersectionality, the ways our various subject positions complicate one another. The work I did in women’s studies taught me to examine my racial privilege and my class privilege, and at the same time, it helped me develop a lexicon for examining more marginal aspects of my identity in terms of gender and sexual orientation. I was taking those graduate classes in women’s studies and eventually teaching undergraduate classes in that discipline, and all the while, I was writing SIX, so that influence is undeniable. I care very deeply about all the forces at work on individual lives in this culture, and the more I write out of my own identity, the more I hope I’m connecting with others, finding those places of common ground.

Shelf Unbound: You include some pop culture references such as movies in these poems, which places them in a specific era. What is your intention there?

Wade: Well, the book has a publication lag time of a full decade from when it was completed in 2006-07 to when it will enter the world in the fall of 2016. Some of the popular references in SIX were current at the time of writing but now are a bit dated. Others—the majority, I think—were already dated at the time I referenced them, and part of this is what my partner and I refer to as “the generic time warp.” I grew up in a family that cherished depictions of the 1950s in film, television, and radio for their “wholesomeness.” Some of the 1960s and a little bit of the 1970s made it into our family cosmology, but very little of the 1980s and 1990s in which I came of age was included in my own popular culture education. My parents actively screened out—pun intended!—anything they felt was “racy” or “edgy” to them, anything that I might call now “liberal” or “progressive.” So I came of age listening to music and watching movies that were, for the most part, the music and movies of my parents’ youth. I still find that when I scan my own popular culture associations and references, they seem more like those of a person born in the 1940s or 1950s, not of someone born in 1979. So back to individual differences and idiosyncratic subject positions! Overall, I see SIX as both a personal poetic inventory of my middle twenties and as a zeitgeist project. The book explores what it’s like to be a particular person—woman—lesbian—lover – poet—moving into autonomous adulthood and domestic partnership in the first years of the new millennium. This book sits squarely between the passing of Defense of Marriage Act in 1996 and the passing of nationwide marriage equality in 2015. I wrote SIX hoping it would be an artful project, formally innovative as Bruce Beasley inspired me to be. But because of the time lag in publication, SIX has also become an artifact of a particular cultural moment even before its publication. To that end, I hope it will resonate with readers who came of age during that era or readers who remember that era well and also with readers whose own coming of age (and perhaps also coming out) has happened since SIX was written—readers who may not have had reason to look back until now.

Shelf Unbound: On page 24 you mention the line, “of actions unprovoked, of consequences unexpected.” Do you think that can apply to writing as a whole, or you when you finish writing a book?

Wade: Yes! I think so much of what SIX is about is the process of trying to name myself and the communities to which I belong and also about trying to name or trace aspects of the creative process. It is a very meta-volume, so thank you for noticing! I had no idea when I wrote SIX if it would ever get published. I’m sure I am not alone in this pervasive uncertainty. In fact, I thought my project was so experimental/unconventional in its form that I shouldn’t make it my thesis project for fear that I would be denied my MFA if my committee did not appreciate my aesthetic choices. That’s the main reason why I kept it as my “shadow thesis” during my years in the MFA program at Pitt. Ultimately, I sent the book out for eight years before I received the good news that C.D. Wright had selected SIX as the winner of the 2014 AROHO/To the Lighthouse Poetry Prize. This was extraordinarily serendipitous, since C.D. Wright was one of the poets I had begun reading back in Bruce Beasley’s class—one of the poets whose influence on the form of the book was most vivid in my mind as I wrote. All told, in terms of “consequences unexpected,” the book was outright rejected more than a hundred times, and it was a finalist for 36 prizes. The challenge lay in persisting, not knowing if the book would ever be the winner or ever be the chosen manuscript for publication anywhere. Now, of course, in retrospect, the selection by C.D. Wright is so gratifying that it feels entirely worth waiting for. In light of C.D. Wright’s recent and untimely death, the book of SIX poems also contains a seventh—an elegy for the poet, written just a few months ago after I learned of her passing. That, too, was an unexpected consequence, and writing a poem for C.D. Wright was the best way—or at least the only way—I knew to honor her memory.