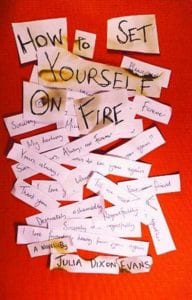

About How to Set Yourself On Fire

Sheila’s life is built of little thievings. Adrift in her mid-thirties, she sleeps in fragments, ditches her temp jobs, eavesdrops on her neighbor’s Skype calls, and keeps a stolen letter in her nightstand, penned by a UPS driver she barely knows. Her mother is stifling and her father is a bad memory. Her only friends are her mysterious, slovenly neighbor Vinnie and his daughter Torrey, a quirky twelve-year-old coping with a recent tragedy.

When her grandmother Rosamond dies, Sheila inherits a box of secret love letters from Harold C. Carr—a man who is not her grandfather. In spite of herself, Sheila gets caught up in the legacy of the affair, piecing together her grandmother’s past and forging bonds with Torrey and Vinnie as intense and fragile as the crumbling pages in Rosamond’s shoebox.

As they get closer to unraveling the truth, Sheila grows almost as obsessed with the letters as the man who wrote them. Somewhere, there’s an answering stack of letters—written in Rosamond’s hand—and Sheila can’t stop until she uncovers the rest of the story. Threaded with wry humor and the ache of love lost or left behind, How to Set Yourself on Fire establishes Julia Dixon Evans as a rising talent in the vein of Shirley Jackson and Lindsay Hunter.

How to Set Yourself On Fire is your debut novel, tell us a little about it.

JE:At its heart, I think this book is a love story. This book follows Sheila, a woman in her thirties who is a bit of a deadbeat, obsessive, and filled with a sadness she has a hard time wrapping her mind around. She struggles to coexist with everything else around her: She can’t hold down a job or friends, until she gets to know her neighbor and his brilliant 12-year-old daughter Torrey. After Sheila’s grandmother dies, she inherits (i.e. steals) a shoebox full of letters her grandmother kept a secret, and as the book unfolds, Sheila and Torrey unravel who this mysterious man was.

Tell us a little about yourself and why you wrote How to Set Yourself On Fire. Where did you get the idea?

JE:I started writing this book as a short story, actually, revolving around a different character. But I instantly fell in love with Sheila and wanted to tell her story. I think it’s really important to let characters, particularly women, be unlikeable. I also loved that Sheila struggles with mental illness—depression, obsession—sort of in the background to the story but unavoidable.

What influenced you to want to be a writer?

JE:I often feel like I missed out on that traditional writer origin story! I don’t really have a memory of always writing stories as a young child, and in fact what I do remember is always having diaries and journals with just a few pages filled out. I remember a total lack of discipline for writing! I think the first time I can remember wanting to be a writer was towards the end of my senior year of high school, when I read Franny and Zooey by Salinger and loved this idea of something breaking the only fiction forms I had ever known: novels/long-form things or short stories. This was somehow neither and both? It inspired me to find innovative fiction and also want to write it. But I didn’t really take it seriously until I became a mother in my twenties and suddenly had this compulsive urgency to create, have creative agency, and probably also expel some of the darker things in my head.

Is this a project you have been working on for some time? Tell us a little bit about the process.

JE:I started writing this in 2013—feverously, writing for hours a day at first—but didn’t really feel like it was much of anything until late 2015. I wrote so much of the story in one go, and then it felt like it took me a year and a half to write the ending. There’s a point with the plot where I as a writer needed to decide what to do about the other set of letters, the ones Sheila didn’t have, the ones her grandmother had written as replies to this man. And once I finally cracked that, I could write the ending.

The process and the length of it, in hindsight, feels so prohibitive to creating new work. I used to wonder how people write a book in the first place. Now I only wonder how anyone ever writes another book.

How much of yourself did you put in your book? Is there a connection to your life and the characters?

JE:I think there’s some of me in Sheila. But she’s very measuredly different. Her circumstances and childhood are nothing like mine but sometimes I think she’s like this version of me that’s stripped of social niceties or decorum. But the plot was inspired by finding a stack of letters an old boyfriend had sent me when I was a teenager, and I had zero recollection of what I must have written to him. The mystery of it, coupled with how nowadays we see the whole archives of correspondence in gmail threads, really fascinated me.

What was the most challenge part of writing the book?

JE:Finishing it.

What is your favorite part of the book?

JE:There’s a quiet scene where Sheila and Torrey are in a church they snuck into, and just kind of sitting there and Sheila is playing with the end of Torrey’s shoelace. I don’t know why that scene gets to me so much but every time I come across it, I feel it.

No spoilers, but tell us something readers won’t find out by just reading the book jacket.

JE:Sheila is pretty obsessed with PBS. I think there’s at least three scenes where PBS plays a weirdly important role.

What is the most important message behind your book that you want readers to understand?

JE:Maybe that darkness is not always solvable and that’s okay. And that friendship and companionship can be unexpected and unlikely and untidy.