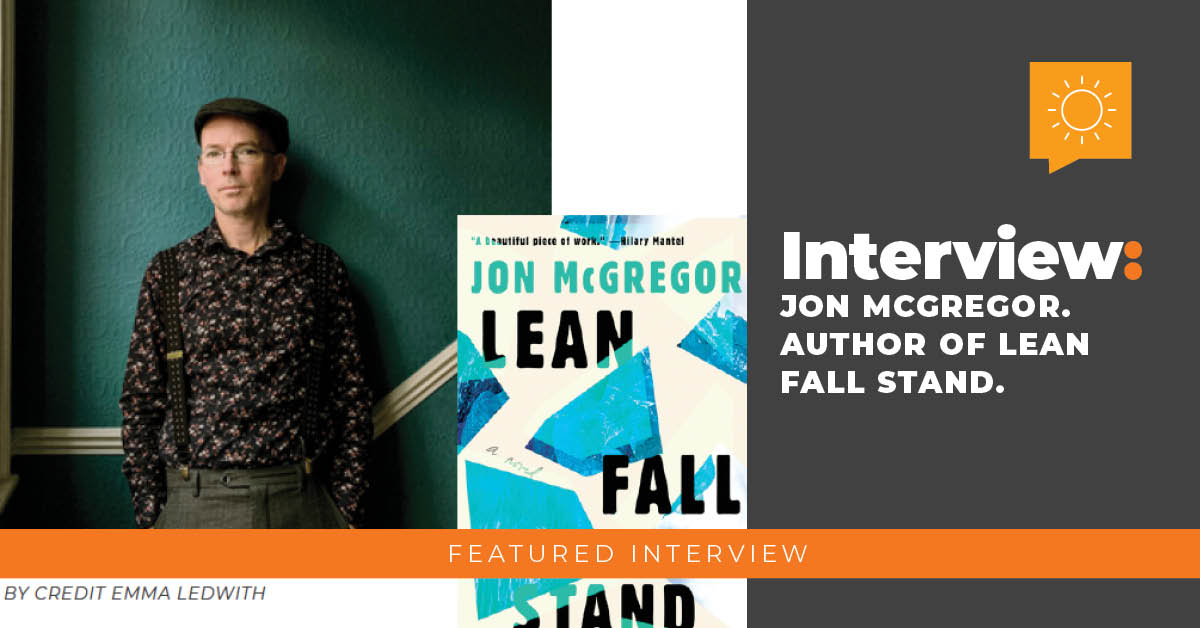

By Anthony Carinhas

In a recent interview with Alex Clark in the Guardian, there was a section which caught my interest. It had to do with your travels to Antarctica to write a nonfiction book during your enrollment at a residency program for writers in 2004, but the project was set on hold for several reasons, one because you never actually got to Antarctica since the boat got stuck in a sheet of ice, and two, your wife was pregnant with your first child. What challenges did you face converting a nonfiction story into one of fiction despite the setbacks?

JM: Well, a minor correction – the Antarctic residency was never intended to result in a non-fiction book. I’d gone there on the implicit promise of writing fiction drawn from the experience, an implicit promise it took me seventeen years to fulfill. There were several things that kept the project stalled: the peculiar disappointment of the trip not coming off as planned (I spent a lot of time on a ship, waiting for the trip to begin, and then it turned out that that had been the trip all along); my doubts about the sense of turning an interesting real-world experience into fiction; the inadequacy of language when faced with the task of capturing or containing or conveying the epic scale and otherworldliness of Antarctica.

The title of your book is what divides the novel into separate parts. In part one, Lean, Robert “Doc” Wright and two other young scientists travel to Antarctica to conduct research. A violent storm quickly develops, separating them from one other in a claustrophobic sense of survival as the story begins. In the second part, Fall, “Doc” encounters extreme health challenges that usher his wife, Anna, into the plot. As she cares for him in the hospital, we find part three, Stand, with the two of them in a support group where “Doc” reconciles the damage the storm inflicted upon his well-being. How did a seventeen-year gap change the scope of Lean Fall Stand? What made you come back to it after publishing numerous books between that time?

JM: The seventeen-year gap was partly the result of the creative challenges outlined above, and partly the result of family life, and partly the result of getting distracted and writing other books along the way. It needed time, I think, to let my ideas about Antarctica settle down and become something far enough removed from what I’d actually experienced. Several times I decided I wasn’t going to write the book at all, but each time I went back to my notes and sketches it felt like unfinished business. What finally gave me enough of a jolt to finish the book was the idea of taking one of the men away from Antarctica and throwing him into a very new and very different situation and set of challenges – the life of a stroke survivor. I became deeply fascinated by the challenges of living with aphasia (a condition that limits someone’s capacity for language), and by the challenge of writing about that effectively. Of course, getting my head around that challenge took some time…

As “Doc” and Anna navigate their new life together, like all major disasters, accidents can change everything in a matter of seconds. Since these two scientists were used to living independently from one another for long periods of time, Anna encounters a deep struggle with her new role as a “carer.” What did you find fascinating about “Doc’s” frustration with his newfound immobility and the challenges he faced after developing aphasia?

JM: As a field technician working in Antarctica, Robert “Doc” Wright is someone who has spent his life fixing things. When a piece of equipment is broken, he repairs it or replaces it; when a process is failing, he improves it. One reason the incident he is involved in goes so badly is because his first instinct is to fix it himself, before seeking help. So his response to his stroke is just the same: give me therapy, and I will fix myself. His frustration – and his anger, depression, etc – comes from the fact that recovery after stroke is not a simple process of fixing in this way. Some of the damage cannot be undone. Some of the mobility and communication deficits will remain. There are strategies for adapting and working around those deficits, but Doc takes a long time to recognize that those are different from “fixing” himself.

(My hunch is that this need to fix things is more often found in men than in women, and Doc’s narrow understanding of his own maleness is a key part of the book, and of his marriage.)

Antarctica with its minimal population and extreme remote location, how did the isolation affect your work? Did John Carpenter’s 1982 The Thing ever come to mind while you were making your way down there? Have you considered a sci-fi novel as a possible venture? How about horror?

JM: That’s really interesting. I mean, I can definitely relate to the valuing of solitude and silence; and I certainly get the impression that for a lot of people who work in Antarctica, that’s part of the appeal. That comes across in a lot of the Antarctic literature, going right back to the early explorers, but it also features in contemporary accounts. People find value in that space, and that quiet. But at the same time, that peace and quiet exists within the context of a substantial safety net: the generators (or the paraffin stoves) are running to provide heat and light, the ship will dock at the end of the season to take you home; the aircraft are on standby to get you out in an emergency. If that safety net failed, how would your experience of the solitude and silence then change? I mean, that idea in itself is more than enough sci-fi and horror for me.

Reservoir 13 carries the same sense of urgency and pace as Lean Fall Stand. A style your readers praised in Reservoir 13, a story concentrated around the disappearance of a 13-year-old girl and its affects on life in a small remote English village. Like Lean Fall Stand, you place the reader in a position where life goes on after a tragic event. This theme was explored in your first novel from 2002, If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things, and I think many of your readers really enjoy the vivid realism present in your writing as you give life to complex characters. Like you, I find average people interesting. Can you tell us why you think it’s important for people to step back and observe the world how ordinary people do? How did you manage to transcribe that compassion without the typical existential pessimism?

JM: I think the key term here is ‘complex characters,’ rather than ‘average people’ or ‘ordinary people.’ I’m pretty convinced that there is no such thing as an average or ordinary person, and that in fact all of us are complex characters with an extremely messy mixture of experiences, understandings, perceptions, relationships, habits, tastes, opinions, and so on; and that most of us have trouble even understanding ourselves, let alone other people. I think that what you refer to as ‘compassion’ is simply fascination and curiosity. A lot of people – most people? everyone? – have unexpected elements to their lives, and unexpected reasons for doing things. I just always want to know what those things are. I keep asking questions.

With all the books you’ve written, it wouldn’t be fair if I didn’t reveal a favorite in your collection. But since I have you on the line, I want to tell you how moving and powerful Even the Dogs was for me. Though I’ve never had a drug problem or been in recovery, I’ve met and known many who did. Hearing their stories always moved me not because they were sad, but their willingness to reveal the truth behind their misery became something to learn from. But the way you talk about the underbelly of our current society, alcoholics, drug addicts, the mentally disturbed, as well as the abandoned and hopeless who live in every town and city across the world. Some of the characters are even ex-military coping with their post-traumatic issues, but the takeaway is how believable the characters are. What compelled you to write a story that follows a series of ghosts who die from a bad batch of heroin, and how they arrived at their current situation?

JM: Well, I’m never sure that compelled is the right word… the first starting point was that I heard about a man who died in his flat and was undiscovered for several days, from my then-wife who was working with people struggling with addiction. And the key point about the story was that it wasn’t all that unusual. I got to thinking about it, and playing around with various ways of writing the scene. (I was listening to a lot of Godspeed You Black Emperor, I remember, and thinking I could write at the same pace they were playing: loud loud fast slow quiet loud. I couldn’t really keep it up.) I did a lot of research about life on the street, and addiction, but kept putting the book away while I worked on other stuff. It was only when I stumbled on the use of the choral voice, and the notion of that choral narrator being invisible in some way, that I found the kick-start I needed to write the book. It was a satisfying technical challenge quite outside the rather bleak subject matter, and that kept me going. It was – and people always look at me strangely when I say this, if they’ve read the book – a lot of fun to write.

2020 unleashed a boom of creativity among artists in the industry, whether that happened through music, art, or writing during the global lockdowns. Considering you did everything to protect yourself and your family in these unprecedented times. How did you utilize the time outside the family spectrum? Have these turbulent times spawned a new book or are you taking the time off to focus on other projects outside the world of writing?

JM: There’s no big story here, I’m afraid. Like everyone else, we blundered our way through the lockdowns as best we could. With some panic and anxiety in the very early stages, and then with some rapid adaptation to online working and schooling. There were rotas, and colour-coded timetables. We were shielded from the pandemic, mostly: our work easily shifted online, and our jobs were pretty secure. We were able to keep our heads down in a way that many many people were not. Anyway, the point is: writing happened alongside all of that, as it always does. I probably had less time to write than usual, but I got some done. I also got pretty good at table tennis.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October / November 2021 Issue: Read Global.