FIRST SEVEN LINES:

“It’s 6 a.m. I’m lying on a bench in a Bus Station, the only traveler to have gotten off here, staring across the concourse at the shuttered café, imagining it open, myself outfitted with a coffee and two rubbery muffins alone at one of its tables, waiting for the bus that’ll take me somewhere else.

I’ve given up on all the people and engagements in the last phase of my life in order to come here, just as, before that, I gave up on the previous set of people and engagements in order to go there, and before that, and before that …

After cashing out of the last situation, I have enough saved to lay low for a year or two, depending on the cheapness of life in this Town. Longer if I earn anything, as I sometimes end up doing. I’ve lived like this, heading over Westward, away from whatever places and people I’ve happened to come in contact with. This has, so far, seemed the only viable attitude toward being mortal, which I’ve been told I am.”

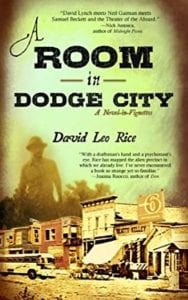

Shelf Unbound: You wrote this novel in monthly installments at aroomindodgecity.com and are now continuing the story there. How did this writing process work?

David Leo Rice: I was initially working on another novel that had ballooned out to an absurd size and I felt really stuck and discouraged with it, so at some point in 2011 or ’12, I decided to start a related but separate project where I’d post chapters, or vignettes, online. When I started the Dodge City site, my only rules were that all the action had to happen in “Dodge City” (though the definition of this place has always been fluid), and that I couldn’t keep any notes or peripheral materials—every idea I wanted to use had to somehow be worked into the chapters themselves. This forced me to self-edit in a way that was really helpful, and the whole process became a lot more fun. The work of turning it into a coherent book came later, and was a lot harder, but at first it was pure joy—it felt like I was cheating on my other novel in a way that needed to happen at that point.

Shelf Unbound: The unnamed narrator is stuck in a nightmarish version of Dodge City and encounters strange and disturbing characters and rituals while there. How did you decide on Dodge City for your setting?

Rice: Two of my biggest interests are film and the dark heart of America/Americana. Dodge City is the nexus of the two—it’s a real town in Kansas, but also the site of so many Westerns and general Western lore. It’s a focal point for the violent and often bizarre stories that America tells about its own origins and essence through the medium of film. Because Dodge City is as much a film set as a real town, it seemed like a place where a lot of dreamlike and fantastical events could plausibly occur.

Shelf Unbound: Amid all the strangeness you also drop in some references to real people—a Lucian Freud exhibit at the local high school, an “Alan Lomax lookalike standing in a corner with his tape recorder.” What interested you in mixing real and imagined?

Rice: I’ve always been interested in surrealism, but I find it more interesting and disturbing when it’s grafted onto, or even indistinguishable from, the real. This feels more true to life: we consider the lives we’re living to be real, and yet things we don’t understand are always happening around us and within us. Mixing crazy and bizarre imagery with real people and real places felt like a way of getting at this feeling, and making the situations harder to dismiss. If something strikes me as 100% fantastical, it’s easy to separate it from my life, but if something is 50% fantasy and 50% reality, that’s a thornier and more provocative place to be. Dreams work this way too: they’re constantly combining the familiar and the unfamiliar. The underlying sensation is that the familiar is stranger than we’d like to think, and the strange is more familiar. For me, this is where the surreal takes on genuine power. There’s also something very American about this kind of reckless combination, in which all sorts of ideas are mixed together with no understanding of their origins, context, or consequences.

Shelf Unbound: For people who haven’t read the novel, how do you describe it and your writing style?

Rice: It’s a series of linked vignettes about an anonymous Drifter who drifts into Dodge City and finds it impossible to leave. He loses what little identity he had as he explores the town’s strange history and gets to know its residents, until he begins to wonder if perhaps he’s been here all along. In this sense, a new identity starts to develop. I hope the style is “accessibly bizarre,” in that, sentence by sentence and page by page, it’s easy to follow and get involved in, and yet overall it takes you to a place you hadn’t expected to go. It’s brutal but also darkly funny.

Shelf Unbound: Is the Drifter the main character in the next part of the story?

Rice: Indeed. The next part of the story—Volume 2—follows the Drifter’s attempt to become involved with The Dodge City Film Industry and to take on the legacy of Blut Branson, a godlike Dodge City filmmaker who rules the city’s dreamlife with an iron fist. In a way, it’s a coming-of-age novel, as the Drifter tries to find his own voice within the gigantic shadow cast by Branson and his films, which the people of Dodge City worship as Holy Scripture. It has some “anxiety of influence” elements, and some considerations of fascism and how film often works as a form of mass mind control.

Shelf Unbound: You have a B.A. in Esoteric Studies from Harvard. How have your studies in this field influenced your writing?

Rice: Definitely. The full name of the major was “Esoteric Studies: Mysticism and Modernism in Western Thought.” The basic idea was to look at medieval mysticism (mainly German) in combination with 19th and 20th century literature, and to draw connections between them on the hypothesis that not much has changed in how people really think when they’re uninhibited. Reading some of these deranged medieval mystics at the same time as Freud or Faulkner, it wasn’t hard to see a through-line. In each instance, people were looking for a direct connection to the divine or the satanic or the primitive, or whatever it may be—something beyond the banal, and yet accessible only through the banal. If I can access a feeling of otherworldliness in a Wal Mart or a Motel 6, rather than in a monastery or a cathedral, that’s much more profound to me. I distrust organized religion, but I’ve always been a solitary seeker, so I’m drawn to stories of individuals trying to forge spiritual connections beyond (or deeply within) themselves. This is what reading and writing are to me.

Shelf Unbound: Who are your literary influences?

Rice: A few key ones are Beckett, Ballard, Lispector, Faulkner, Murakami, Mishima, Kobo Abe, Thomas Bernhard, Marquez, Kafka, Alan Moore, Flannery O’Connor, Brian Evenson, Blake Butler, Cesar Aira, Annie Baker, and Steve Erickson. The author whose work I’m most interested in getting to know this year is Iris Murdoch.