By Alyse Mgrdichian

Poetry is a powerful catalyst for lots of things, especially empathy and a deeper understanding of self. It is, in my opinion, the most vulnerable art form – writing poetry means baring your soul on paper for strangers, which takes a lot of courage and self-love. And if not self-love, then self-

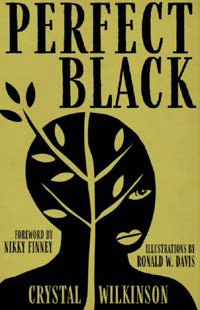

acceptance. With that in mind, I was very grateful and humbled to receive a review copy of Perfect Black, a debut poetry collection from Crystal Wilkinson (published on August 3, 2021 by The University Press of Kentucky). It is a beautiful and tragic collection, filled with heartbreak and hope, which made me very interested in interviewing Crystal and learning more about her experience writing it. Below you can find the book’s synopsis, along with our conversation.

SYNOPSIS: Perfect Black

Crystal Wilkinson combines a deep love for her rural roots with a passion for language and storytelling in this compelling collection of poetry and prose about girlhood, racism, and political awakening, imbued with vivid imagery of growing up in Southern Appalachia. In Perfect Black, the acclaimed writer muses on such topics as motherhood, the politics of her Black body, lost fathers, mental illness, sexual abuse, and religion. It is a captivating conversation about life, love, loss, and pain, interwoven with striking illustrations by her long-time partner, Ronald W. Davis.

INTERVIEW…

Could you walk me through your professional journey as a writer? How did you get started, and what made you commit to the field?

CW: My journey as a writer began before I knew that I was on the path. As a quiet girl, I was drawn to books—reading and writing were the only things that motivated me. After college, I began working in public relations with a journalism degree but knew my passion was writing stories. About twenty years ago I decided to go back to get an advanced degree in creative writing at Spalding University. I did this for two reasons. Firstly, so that I could teach college courses and slowly move away from my public relations career. And secondly, because even though my first short story collection was published and I had a contract for my second, I wanted to be immersed in craft. I had also already been teaching creative writing courses at a local writing center, as well as some college level courses, but I wanted to teach full time.

Could you tell me about your experience writing and publishing Perfect Black? It is such a deeply personal and raw book, so I’m wondering what it was like to explore all those different facets of yourself.

CW: One thing is, I’ve always written and loved poetry, probably even more than prose, so there was this sort of protection of my poetry and not wanting to reveal it as much to people—a kind of coveting of the small wonders of poetry, more so than prose. I think part of what we all do as writers is stand before the world naked in some way, and there is a certain vulnerability. But when you are a fiction writer you can put the bones and meat down and there’s a thread of truth, and it’s kind of fun because no one knows how deep or wide the thread of truth is. You can do that in poetry, but when I write poems I think that those vulnerabilities are on the surface more.

Even if there is clearly a speaker of the poem who is not me, the truth is always right at the surface, instead of buried deep down the way I’m inclined to write fiction. So that awareness of vulnerability was much different for me in this book than my other books because it is not as hidden. Before I would sprinkle a bit of myself or familial truth into my character, but it just stands there in a poem, like these stalks of truth. I also play with a range of form—two-line stanzas, longer poems, the lyric, the formal. Writing the poems were one process and compiling them into the book was another. As some poems and lyrics fell by the wayside and I began to look at them as a collective, and start thinking about them thematically, then it became even more frightening in some ways because I said, ‘Whoa, there’s a big truth there. Oh my God, here this is.’ When I’m writing fiction, I always think of these storylines sort of like clotheslines, like this is a through line, now what scenes are going to hang on this? Like if there is a through line of a mother-daughter relationship, what scenes am I then going to put in the novel that I’ve already written, or that I need to write, that will solidify that storyline, or the mental illness thread, or whatever themes there are in the book. In some ways the same thing happened with this. I hadn’t really planned on writing a memoir in verse, but a lot of the poems that were heavily threaded with topics that were more away from me or in styles that were more away from my truth began to thin out.

A good poet friend, Rebecca Gayle Howell, looked at the poems for another project and said, “I think you have a collection” and I said, “No, no, that’s not what I do.” So, we began to look at it together, at some of the sections and what they were doing. In some ways it is almost like a contrapuntal. And I mean that in the loosest of ways. If we look at it as a memoir in verse, the first section is coming of age, the second an awakening, third, sort of grown woman poems, so it can be read that way. But also, you can look at the grandmother poems by themselves, or the grandfather poems, or look at the poems that look at women’s bodies that tie in about sexual abuse. There’s a variety of ways to look at them. Thematically the poems can be examined, can be read backwards and forwards. Even the illustrations can stand alone and be in conversation with the reader, but they are also doing something else in the call and response they play with the narratives in the book.

For Perfect Black, what was it like collaborating with Ronald Davis for the illustrations? Creating artwork for poetry can be difficult — what was communicating and workshopping like for the both of you, especially considering that he’s your romantic partner?

CW: “Ron and I have always wanted to write a book together. In some ways, this book is the child that we never had. We are independent thriving artists on our own. He has his third book coming

out this year with Wayne State University Press, but it was so much fun to do this projec together. It’s something we’ve always wanted to do. The process of making these decisions of what art should be in conversation with which poem was an interesting and elevating process. I think it did something for us both artistically. We are able to look at each other’s work differently and step deeper into each other’s psychological landscapes. Just when we thought we

knew everything about one another as artists, as a couple, then there was another layer to discover in this process. It was fun—tension arose and dissipated, rose and dissipated, until we got it done. I think we are both better off artistically for that shared process.

I see that your main fields of interest are poetry, food writing, and short stories. Do you see a connection between these different art forms? And what different areas of yourself are you able to express through them?

CW: Of course they are all connected. One of the things I’ve learned about myself as a writer in recent years is that the poet doesn’t live in one house, the fiction writer in another, the essayist

and food writer in yet another. I live in a hybrid space as a writer. My stories are poetic. My novels have meter. Recipes are poems. Essays are lyric. I’m no longer looking at those leaps as negative. It’s such a wonderful thing to have a notion of craft but to also be able to return to my highest creative self. It’s been such a relief and such a joy to not see myself as a broken writer or to see that longing to fracture the narrative as a negative thing.

Speaking of, could you tell me about your fiction? What themes do you usually explore through your stories?

CW: My fiction is a way to explore issues in the world, primarily the worlds of women and the people who love them. Part of my process is to begin with a character who I’ve patiently waited

to blossom in my head to become a full blown living breathing person. Then curiosity takes over and I find out everything I can about that character, their families, coworkers, towns, their lives. What’s always surprising to me as a fiction writer is that, even though the plan might be to write a life so different from my own, it always circles back in funny, often surprising ways. I explore

Black women in Appalachia and other places and circumstances too, but Black people in a rural landscape captures me and doesn’t let go. I explore themes of gender, coming of age, sexism,

racism, mental health, and sexual abuse, among many other things. The characters and their lives always guide what the theme becomes.

Could you tell me a bit about Praise Song for the Kitchen Ghosts, your upcoming book? What has the process of writing and publishing been like for you?

CW: This will be my fifth book, a culinary memoir. Again, I feel such a sense of relief to be able to explore a variety of genres but to still be able to write a book about my matriarchal ancestors going back to 1795 using archival research, history, poetry, fiction and the lyric essay form all in the same book. I’m really excited about the experimentation that my editor allowed me to do with this book and I hope that readers will respond to it.

What advice would you give to your younger creative self? What do you wish you’d known going into this field, and what’s one thing you’d like to tell newer writers?

CW: Imitation is a form of flattery but I wish I’d known sooner that I could invent ways of being, ways of doing. I spent so many years looking for a model for The Birds of Opulence (my novel) not realizing that it was okay to forge a different path no matter how unusual it may be. That’s what I’d say to a young writer. Flex. Learn the rules, the craft, but also stretch and strut your own

art the way you see fit.

Crystal Wilkinson a recent fellowship recipient of the Academy of American Poets, is Kentucky’s Poet Laureate. She is the award-winning author of Perfect Black, a collection of poems, and three works of fiction—The Birds of Opulence , Water Street and Blackberries, Blackberries. She is the recipient of a 2022 NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Poetry, a 2021 O. Henry Prize, a 2020 USA Artists Fellowship, and a 2016 Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence. She has received recognition from the Yaddo Foundation, Hedgebrook, The Vermont Studio Center for the Arts, The Hermitage Foundation and others. Her short stories, poems and essays have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies including most recently in The Atlantic, The Kenyon Review, STORY, Agni Literary Journal, Emergence, Oxford American and Southern Cultures. Praise Song for the Kitchen Ghosts, a culinary memoir, is forthcoming from Clarkson Potter/Penguin Random House. She currently teaches at the University of Kentucky where she is Professor of English in the MFA in Creative Writing Program.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the February / March 2023 Issue: Connection.