Shelf Unbound: What’s a typical starting point for you in writing a story, for example the boy coming of age in the title story, with typewriter and computer metaphors throughout?

Alejandro Zambra: I think that literary genres are like shirts you can put on, but they always feel a little uncomfortable. In a certain way, writing is reaching the point where that shirt takes on the shape of your body. I never think to myself, “I’m going to write a story,” or a novel or a poem. I just take note of the images that interest me, and then I start to “observe” them, to try to penetrate into the secret that always appears when we look at things up close. More than methodical, I’m very obsessive. In the case of that story, the image came to my mind of my mother typing on the typewriter, very concentrated, using all her fingers. And the rest came from there, trying to situate that image, to focus on it. Now, after having written it, I can see that the whole story revolves around writing, especially the writing of those who don’t write literature, like my father and my mother.

Shelf Unbound: How do you develop your characters, such as the man trying to quit smoking in “I Smoked Very Well”?

Zambra: Oh, I’ve been that character who tries to quit smoking many times. Right now, for example, I’ve gone seventeen minutes without smoking.

Shelf Unbound: Do you have a favorite story in this book, and if so which one and why?

Zambra: Yes and no. It’s a question of affection, really. I couldn’t say which story is the best of the book; I’m the worst person to comment on that. I have a fondness for “Family Life,” but that’s because I remember the time when I was writing it—a horrible time, when the only good thing was to open that file and read it and add or take out some sentences. Or maybe it’s because lately I’ve been “rewriting” it—or tinkering with it—for the screenplay of the film of the same name, which we will be shooting soon with the directors Cristián Jiménez and Alicia Scherson. The story “True or False” also provokes that feeling of closeness in me. But all the stories are children I love.

Originally there were twelve of them, but I wanted eleven, for a superstitious reason: I wanted eleven like Yates’ “Eleven Kinds,” and like Kafka’s “eleven sons.” Maybe the story I like the most is the one that was left out, but that later became Facsímil, the book that just came out in Spanish.

Shelf Unbound: How do you find the entry point for your short stories, such as the first line of “Memories of a Personal Computer”: “It was bought on March 15, 2000, for four hundred thousand eight pesos, payable in thirty-six monthly installments.”

Zambra: The image that gave birth to that story—an image that also appears in the story “My Documents”—was of someone warming their hands on a computer’s CPU to fight the cold. But when it became a story, that first sentence came to me immediately. Sorry, I’m bad with “how” questions. I’m more about trial and error, so it’s difficult to say precisely how I came to something; what I like is errancy.

Shelf Unbound: A short story is like _______

Zambra: A shortcut you take without knowing where it leads.

Shelf Unbound: What is the appeal for you of writing short stories?

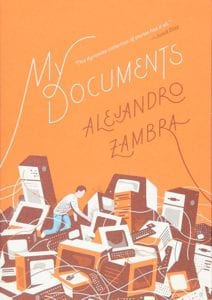

Zambra: Before this book, I had written stories only occasionally, and pretty few of them. I like to write books, that’s what I enjoy the most. And My Documents originated as a remembering of moments, of texts, but it changed along the way and in the end I wrote it as a book. Almost all the texts are, so to speak, simultaneous; I wrote them over the course of a year, basically. And they’re all half-siblings, step-brothers. They all share a mother, which is me. I’d say that what I like about stories is their extreme intensity, but I also look for that intensity in a novel or a poem.

Shelf Unbound: If you were teaching a course on short story writing, what is the primary piece of advice you would offer?

Zambra: That they not take the course, and instead invest that time reading Ana Blandiana, Kafka, Fogwill, Clarice Lispector and Hebe Uhart.