By Alyse Mgrdichian

About the Author

Lazarus Panashe is a Zimbabwean writer and editor. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Civil Engineering that he has not used for two years. His short fiction has been published online and in print in the anthology Brilliance of Hope. He writes from betwixt the four walls of his solitary bedroom, which unbeknownst to his family, is a portal to many worlds

Reading global literature is important for growing your mind and your capacity for empathy. In an age of rapid technological advancements, where communication has never been easier, it has somehow also become easier to isolate yourself in your own little echo-chamber. But where’s the good (or fun) in that? Global lit helps broaden our horizons and our understanding of the world, which I think is crucial for societal and relational wellbeing.

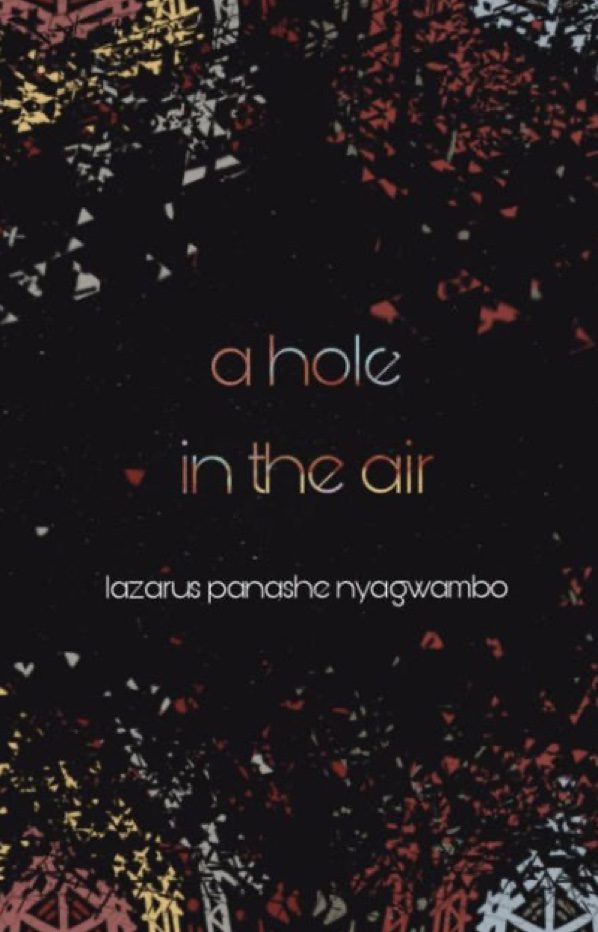

Hailing from Zimbabwe, Lazarus Panashe Nyagwambo released his debut story collection, A Hole in the Sky, on January 17, 2022 with Carnelian Heart Publishing. His stories explore human relationships in the Zimbabwean context, which piqued my interest—I’m always interested in reading different takes on the human psyche, especially from global perspectives. Below you can find a synopsis of Nyagwambo’s book, along with our conversation. Enjoy!

A Hole In The Air

“The air was thick with something unspoken, something opaque yet intangible that filled the gaping holes inside all of us.”

Plagued by abysses that portend eternal nights, curtailed by the jagged pieces of life’s puzzle and bound on all horizons by the faded colours of yesterday, the people in these stories inhabit a world where their characters cease to be firm, self-defined entities and become fluid, ambiguous consciences as they are thawed by their circumstances.

In this compelling debut short story collection, Lazarus Panashe Nyagwambo offers his interpretation of the human condition, delving deep into the psyche of the personas he invents—their perspectives, motives, and emotions—with a vividness that radiates from the pages.

A Hole in the Air is a blend of intriguing stories that are sometimes as comical as they are sombre. Nyagwambo’s prose is as poetic as his reconnoitres of the bonds of love, family and friendship, the strengths of which he tests under the weight of this thing we call life.

To start, why don’t you tell me a bit about yourself and your background?

LPN: My name is Panashe, although I usually go by Lazarus when I’m writing, so my name is Lazarus Panashe Nyagwambo. I’m 25, and I live in Zimbabwe—that’s where I write and work as an editor. I have published one book, and am also a freelance editor, although I hope I can edit fulltime in the future.

Could you tell me a bit about your first publication, A Hole in the Air? And how did you get started as a writer?

LPN: This is going to sound so basic, because I’ve heard this story from so many other authors. I started in school, writing English papers. My teacher said I was really good, so I started writing more. And I’ve always enjoyed reading, so I guess my writing became better because of that. And then I stopped and went to university in another country, and was dealing with some issues there. To deal with them, I started letting out all my feelings through writing. I showed a few friends my work, and they were like ‘Hey, you’re really good at this, you could actually be a writer.’ I never took it seriously. But then I started writing more and reading more, and realized that this was something I really enjoyed.

I had studied civil engineering in school, and planned on pursuing a post-grad degree … but then 2020 happened. 2020 was when I really started getting into the writing space. Other countries were on lockdown, and I didn’t want to do grad school in my home country. I was stuck in one place, which I think made my writing better, because when you’re home with nothing to do but think or watch TV, you start getting ideas.

I learned about online literary magazines, and was like ‘Oh, maybe I should try and submit to one of these to see how people receive my work.’ So I sent some stories, and of course I got rejected. But because I wasn’t really serious about it, it didn’t discourage me much. I continued sending my stories out to more and more magazines, and actually got accepted four times within the span of a month. So that was really encouraging.

Then Samantha, my publisher, found me online and asked me to contribute to an anthology she was compiling of diasporic Zimbabwean authors. I sent some stories and she liked them, wanted to know if I had more, and said that she’d be happy to publish them as a collection if I wanted.

And here we are! Now I have an entire book. In this way, my first collection wasn’t really planned, it was something that just happened to me. I continue to submit to magazines, and hope to work my way up to something like The New York Times. I want people know my name, and I want them to enjoy what I write. So I’m going to keep trying to improve and get my name out there.

Could you expand upon what it was like working with a publisher for the first time?

LPN: Well, when I learned I was getting a story collection, I really only had four stories that I thought were good, but they’d already been published by other magazines—so I had to start from scratch. I had other works in progress, but I’d forgotten about them, so I had to go back to what I had and see what I could use. There were some good stories, but a lot of them weren’t good enough to be published. So I spent the next six months writing the remaining stories for the book.

After that, we went through the whole process of editing and coming up with the cover design. I didn’t realize it was that stressful—I didn’t know what I wanted, but no one could make anything good enough. I’m a bit of a perfectionist. Everything I saw was ‘bad’, but I didn’t know what I wanted, so I ended up doing it myself.

The editing process itself was really annoying because I didn’t want to reread anything I’d written—it felt embarrassing, like watching an old recording of myself. I figured that if there were mistakes then it’d be my own fault, so I just checked the suggested changes and gave it the ‘okay’.

After the book got published, marketing began, which has been really difficult as an indie author. No one knows who my publisher is, so there are no big ads. We’ve just had to be very upfront and aggressive with it … which I’m not good at. I think most writers are introverts, so forcing people to read something or buy something feels weird. That’s the hardest part of working with an indie publisher. It’s nice, though, because they’re able to give you their focus because they don’t have to deal with a lot of people, so there are pros and cons.

Marketing is a major challenge in Zimbabwe specifically, since there isn’t really a reading culture here. The people don’t really want to buy books. I don’t know if you’ve ever read or seen anything about Zimbabwe on the news, but our economy is terrible, so people think ‘Why would I spend money on a $10-$15 book when I need to buy food for my family or I need to send my kids to school?’ It’s the hierarchy of needs, and books are at the bottom. So, I’m writing stories about Zimbabweans for Zimbabweans who don’t like reading. That’s very complicated and difficult to navigate. We have libraries, but it’s more for students who have class reading assignments. You’ll never find anyone who’s like ‘Oh, let’s just go to the library and see what’s new in the African literature section.’ That’s so rare. Poetry is really the only thing people seem keen on.

However, there’s a niche of people who are interested in African literature who aren’t in Africa, especially the African diaspora, so I have a feeling that that’s where my sales may come from.

How has it been publishing a short story collection rather than, say, a novel?

LPN: I’ve learned that stories are really hard to sell in general. People want novels, and I don’t understand why. It’s like the difference between watching a TV show and a movie. It’s easier to watch the show because it’s 30 minutes per episode—making short stories much easier and quicker to read—but a lot of people prefer the full-length thing instead. Hopefully I’ll write a novel one day. However, gaining experience via short story writing is vital.

I was watching a MasterClass from Joyce Carole Oates, and she was talking about how, if you want to become a writer, it’s a lot easier to start with short stories and work yourself up to long-form writing than it is to just sit down and try and write a novel. As an editor, I’ve had to deal with people who tried to start their writing career with a full-length novel, and it’s never—and I mean never—good.

Right. If you start by trying to write novels, you put more effort into your failing than you do if you write short stories.

LPN: Exactly. You can take an entire year writing a novel that isn’t good enough, but a short story can take 2-3 days, depending on your process, and you can easily write a lot of those in a few months and send them all out—statistically, people will like some and not others. You can always add some, remove some, etc., so it’s much easier to do that.

What would you say is the heart and inspiration behind your stories?

LPN: When I started writing, as I told you, it was when I was dealing with some difficult stuff at uni. I was pretty much journaling but changing the names of the people involved and turning them into fictional characters. Eventually, my writing naturally evolved into a commentary on how I see the world, or how I think other people see the world. Basically, it’s a commentary on life and the complexity of it. Whenever I write a story, I try to never have black and white, good and evil, Superman and Lex Luther … people aren’t perfect, I’m not perfect. Sometimes people have good intentions but go about it in the wrong way, and I try to flesh that out in my work. This world is messed up, but it’s not because we are messed up. We’re trying to deal with everything, but we react to things differently. So, that’s basically what I try to pull from when writing— people are nuanced, and life is nuanced.

In terms of inspiration, observation and listening are such important life skills, and I’m literally always on the lookout for interesting stories wherever I am. Like if I’m in public, I listen for people talking—people here are so loud, they don’t even care where they are, they’ll just talk about their marriage problems on public transport. I always take note of whatever interesting conversations I may overhear, and I write about it later (while withholding whatever sensitive information I may have learned). And of course I dramatize it to make it more interesting, but the heart of it is that I get my stories from the world around me, from real people and real experiences. The world is the richest source you can pull from when writing.

Would you say your stories are literary fiction or magical realism?

LPN: For this collection, it’s definitely literary. If you’ve never been to Zimbabwe, the book will give you a good idea of how we live and how our families behave. Of course it’s dramatized, and I don’t think there’s a single happy ending in that book—my apologies in advance. Our lives are not that sad, I just prefer to show that side of life. However, I’ve been realizing that I find creative, slightly bizarre stories more interesting. Everybody lives through everyday life all the time, so I’ve been trying to get into some really subtle elements of magical realism in my work.

I like it when you’re unsure whether it’s actually magic or not. That’s the sort of fiction I’d like to write. And I’m always working on getting better—my editing role helps with that, inadvertently, in terms of reading a lot of stories from different people with different styles. And I think my writing has become what it is because I’ve read some really good authors in my youth, like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Stephen King, Hardy Boys, Goosebumps, and The Chronicles of Narnia. The more I read and the more I edit, the more skills I can add to my tool-belt.