By Alyse Mgrdichian

Horror, as a form of storytelling, has deep historical roots and is ever-expanding in today’s culture. Whether it be movies, books, or some other medium, humans have, arguably, always had a penchant for monsters. The difference, however, comes when we take a closer look at the differing societal interpretations of those monsters. So, what exactly does this look like?

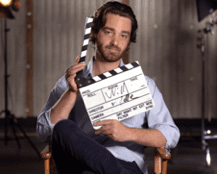

To help me flesh out and answer this question, I had the pleasure of conversing with Professor Will Linn, who contributes to series and documentaries as an interviewee and expert mythologist. With a Ph.D in myth and depth psychology from Pacifica Graduate Institute, complimented by an undergraduate degree in philosophy, Will teaches courses on myth, storytelling, philosophy, and anthropology at Hussian College—a leading film and performing arts college—where he chairs the Department of General Education. Will is also the founder of Mythouse.org, which offers community conversation and deep dives into various mythological topics, including monsters.

Before addressing what differences there are in horror and monsters across cultures, it’s important to recognize what they have in common. When asked about the similarities, Will gave a simple yet effective answer: All of the monsters are something to be afraid of. “They represent our different fears,” he states. “Sometimes it’s a fear of the dark, sometimes it’s a fear of the water, and sometimes it’s the fear of a predator. You look at something like Little Red Riding Hood, and there you have the wolf, who is a predator. So, with horror monsters, no matter how old or new, we are seeing our fears personified. The monster isn’t as scary as the fear it represents. And beneath this personification is our relationship with the fear itself, which varies between cultures.”

A prime example of this difference can be seen in the way ghosts are presented across the globe. As separate societies, we all have different relationships with the dead, and almost every culture has some kind of a ghost in its mythos. When asked to expound on this, Will states that the different versions of the same monster will often reflect different cultural philosophies.

“One of the more overt examples of a ghost revealing a country’s philosophy is the ‘hungry ghost,’ from China,” Will says. “It has a tiny mouth and proboscis neck, through which it has to eat. This creature reaffirms the philosophy of Chinese Buddhism, which believes a person becomes a hungry ghost because they are still clinging to this world and its things. So, it’s greed that you’ve developed during your life that has made you so hungry, which is frowned upon in this tradition. We may all have some version of a ghost, but the ghost stories we tell reflect our different societal values.”

Listening to Will talk, I can’t help but think about the differences in how varying cultures approach the concept of feeding the dead. For example, with Día de los Muertos (Mexico), the dead are respected and loved. The living wish to reconnect with those they’ve lost, so they offer the deceased’s favorite foods. However, while there are communities that feed their dead out of celebration and love, there are others that feed them out of fear of evil spirits. Perhaps the reason for this boils down to different cultural dispositions towards death itself—the inevitability of it may be a comfort to some, but not so much for others.

Observing the same creature within different cultures, like the ghost, not only demonstrates varying societal philosophies, but also reveals a lineage that extends across time. Take the golem, for example. This is one of Will’s favorite creatures: “It originates from a medieval, alchemical Jewish story,” he tells me. “Long story short, the Maharal of Prague creates a creature out of clay and awakens it, usually with the name of God written on a piece of paper, rolled up, then put into the golem’s mouth. The golem of Prague (the original golem) has a lineage stretching both before and after it. There is a long history of stories about creatures that, like the golem, are some kind of un-animated matter that then becomes animated.” This concept is certainly present in earlier stories, like that of Adam and Eve, whose clay bodies are awakened with breath, or Prometheus and the awakening of Pandora.

“The golem,” Will continues, “introduces the mind-body problem. Are the mind and body separate? And if a body is animated, does that mean it has a mind or soul? A good modern example of a ‘golem’ can be found in Fantasia, the Disney movie. When the broom is animated and told to fetch water, it does so mindlessly. This is seen in its inability to stop, which results in a flood. When the Maharal ordered his golem to fetch water, the same scene unfolds. So, with old creatures like golems, there is certainly a lineage, which we continue to see in stories today—from Ex Machina to Age of Ultron.”

This makes me wonder, what about the monsters that aren’t just mythical creatures, but are active antagonists? According to Will, the role of antagonistic monsters holds a higher significance in horror than you may think, because they’re the ones who drive the narrative (rather than the protagonists). Following his contributions to a documentary on the film Alien, Will got the opportunity to learn more about the process of creating the Xenomorph, the film’s antagonistic monster. He also got a few separate opportunities to hang out with Diane O’Bannon, the wife of Dan O’Bannon, who created Alien.

Will tells me he learned that “Dan saw the alien herself as the one on the journey, not the protagonists. So, the alien is the one driving the narrative through her own journey, and everyone is just reacting to it. In our own world, we would like to believe that everybody wants to just ‘do good things’—however, the reality is, most times we’re just responding to antagonism rather than protagonism. Monsters are often what set us up to do the right thing, and they give us reason to be protagonists. In particular, protagonism is almost always the most obvious response to the antagonist’s actions, so the antagonists are, in reality, the ones driving the story.” Whether they be fictional monsters or normal humans who do monstrous things, villains help heroes frame their worldview, giving them a reason to fight. In this way, our antagonists are often inversions of our

protagonists. This relates to the Jungian concept of “shadows,” which are defined as the things that we actively repress or distance ourselves from.

“Our monsters,” Will states, “are often the shadows of our heroes. So, in a very medieval Christian world, you end up with a vampire as the evil figure. Why would that be? Do you see the comparison between the vampire and Jesus? They both go in the tomb and are brought back from the dead, they both drink blood (whether literally or figuratively), they both are symbols of immortality, both have stakes that go into them (into the hands and feet of Christ and into the heart of the vampire), etc. There’s an inversion with them, so while Christ is all about liberating the immortal soul from the mortal body, the vampire will have no immortal soul, but will immortalize the body. So, monsters can end up as a reflection or a shadow of the heroes of our culture.” This is a concept that, even still, we can observe in our modern stories. For example, according to Will, one of America’s most popular modern villains seems to be corrupt, excessively powerful superheroes, since our media is flooded with virtuous supers. If you’ve seen The Suicide Squad (2021), you’ll know that there is an inverted version of Captain America, who is shown to be narcissistic and self-serving behind the scenes. Same with The Boys (2019-present). So, the shadow of our values (mixed with the dark, repressed truth of our culture) often makes an antagonist.

In the end, monsters, both in stories and in real life, have the potential to bring out the best in people—whether we like it or not, the monstrous ones are the instigators, the ones who spur on our “protagonists,” whether they be fictional characters, real historical figures, or even ourselves. However, I’d like to end this column on a different note, specifically with a call to action. Given the differences between cultural philosophies and priorities, we should read the folklore and watch the horror movies of other countries to learn more about them and better appreciate them. Remaking and westernizing phenomenal international films and stories is a very American trend, one which belittles the culture and context of the countries from which they originated. This month, as we celebrate all things spooky and grim, let’s be purposeful in appreciating the horror films, stories, and monsters that other cultures have to offer!

About Will Linn, PH.D.

Will Linn, Ph.D. is the founder of Mythouse.org and the General Education Department at Hussian College. He has appeared in documentaries and series, including Memory: Origins of Alien, Myths: The Greatest Riddles in History, Mythosophia, and The Myth Salon. Between 2018 and 2019, Will served as the Executive Director of the Joseph Campbell Writers’ Room at LA Center Studios. His consulting and courses—for high school, collegiate, post-graduate, and professional storytellers—are grounded in transformational narrative. You can find Will on LinkedIn.

Continue Reading

Article originally Published in the October / November 2022 Issue: Read Global.