By Alyse Mgrdichian

This article is comprised of interviews with various Native authors, split into four parts – children’s literature, genre writing, poetry, and nonfiction (in that order). Ready? Let’s dive in!

INDIGENOUS CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Children’s literature is vital to a thriving society because stories, whether real or fictional, hold up a mirror. Young kids need to be able to see themselves (and those who are different from them) in the stories they read, because our world is a diverse one. With that in mind, I’m glad to have had the opportunity to interview a handful of Indigenous children’s book authors, namely Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee Nation), Kim Rogers (Wichita Nation), Andrea L. Rogers (Cherokee Nation), Art Coulson (Cherokee Nation), and Joseph Bruchac, (Nulhegan Abenaki Nation).

The first thing I asked these writers was, why is it important to write Indigenous stories for youth?

“When I was growing up,” Kim told me, “I never saw a Wichita kid like myself in a book. I wasn’t able to articulate how that made me feel until adulthood, and I never want kids to feel the way that I did – erased. It’s crucial that all children see themselves in a book because this is a reflection of the world we live in. We are all related. Every child needs to be included and see themselves as heroes in stories – it encourages them to go out into the world and accomplish great things.”

“You want to provide stories for Native kids,” Art said, “so they can see themselves in those stories. Growing up, there weren’t a lot of stories written about us, and there were even fewer stories written by us. And for a broader audience, it’s important to show them the everyday life of a native person (beyond what they may be learning in their social studies class). So, even though I write fiction, I try to keep it somewhat real regarding what our day-to-day experience is like. We’re still here, we’re still thriving, and we make up many different vibrant cultures and a lot of different lived experiences. And it’s important to show kids that there isn’t just one way to be Native.”

“When I was young,” Joseph shared, “and even into my 20s and 30s, there were virtually no books by indigenous authors for young people. Not only that, most of the books that did focus on Indians tended to be inaccurate, stereotypical, and racist. I began writing for young readers because I wanted them to have the kind of stories that I did not have. That was especially true for my own two sons, who I often told traditional stories to when they were little. Both of them grew up to be storytellers and writers, and my younger son Jesse is so fluent in our Abenaki language that he founded and directs the school of Abenaki at Middlebury College.”

“The only stories I had in childhood about people I felt I had anything in common with were the stories my father and aunts and uncles told me,” Andrea said. “When I went to school, we weren’t on the bookshelves. And I looked. The closest I could get in the children’s section was a story about a family of sharecroppers. It’s called The Velvet Room, and the main character is a girl who loves books. My white mom’s family always worked someone else’s farm, they were those Okies in The Grapes of Wrath, and in this book by Zilpha Keatley Snyder I saw her family. But there were no contemporary Cherokees on the shelf. It was as if Sequoyah was the last living Cherokee. But of course he wasn’t. I was shocked when my own children were born twenty-five years later and very little had changed. We had Cynthia Leitich Smith, though. I bought all her books for my kids, but she was pretty much it. But her presence let me know that I wasn’t the only one who had noticed and felt our literary extinction. So many writers I meet started writing because our stories weren’t there. There were no books to hand our children, so we had to write them.”

Cynthia agreed. “To borrow from Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s ‘mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors’ metaphor, part of it is reflective. It’s important for Native kids and teens to find characters, biographical subjects, and culturally resonant topics reflected to them in books. It sends the message that they belong in the global community of readers, and that people like them deserve to be centered. It’s also important for non-Native kids to appreciate our three-dimensional humanity and have their mainstream misconceptions corrected. Indigenous stories for youth lift up young readers. They heal. They build bridges. They make society better.”

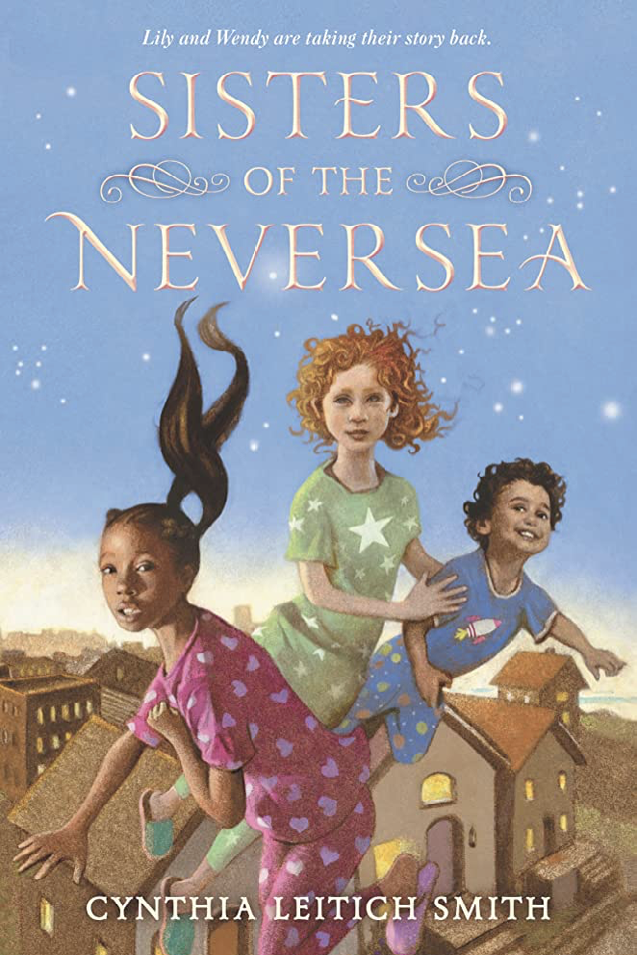

Stories have the potential to highlight underrepresented voices – a good example of this is Sisters of the Neversea, Cynthia’s Peter Pan retelling. She told me a bit about it: “Sisters of the Neversea spotlights the Native and girl characters, including Belle (Tinkerbelle) and a new mermaid named Ripley, as well as Wendy Darling and Lily (Tiger Lily) Roberts, who are feuding stepsisters. The story includes storybook pirates, wild beasts, and many of the elements of the original, but they have been reframed in a way that lovingly invites all children into the magic and adventure.”

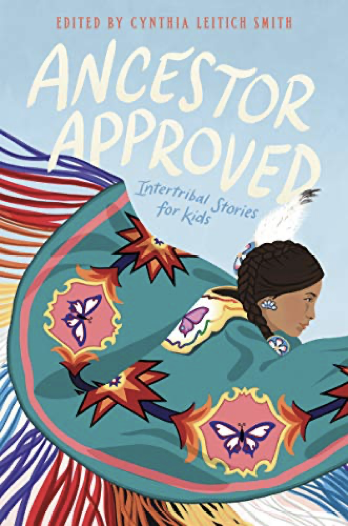

Cynthia is also the author-curator for Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperChildren’s in partnership with We Need Diverse Books, which focuses on North American Indigenous authors and illustrators. Heartdrum’s first publication was Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids, an anthology edited by Cynthia.

“Ancestor Approved,” Cynthia told me, “is an anthology of interconnected short stories, bookended by poems, all of which at least partially take place at the annual Dance for Mother Earth Powwow in Ann Arbor. The creative team was 15 writers, cover artist Nicole Niedhardt (Navajo), plus me. We worked together using a Trello board as our online shared space. Traci Sorell (Cherokee) took point on gathering initial locale information, and then I built on that as questions arose. Writers shared information about their protagonists and plots. A few brainstormed in advance. Once first drafts were in, I reviewed them and then connected respective writers with overlapping themes or characters who had something in common. They conferred for the revision process to make those connections seamless, and several worked together to finish off the end matter, especially with regard to Indigenous languages in the glossary”

Kim added, “I was honored that my poem What is a Powwow? and my short story Flying Together were both accepted for Ancestor Approved. When my editor told me that my character, Jessie, would be featured on the cover, I was thrilled! That was the first time I’d seen a Wichita character illustrated anywhere. Nicole Neidhardt, the illustrator, added so many story details like the delicate daisies in Jessie’s earrings to the beautiful butterflies in her shawl. I have to admit, it made me cry. It was definitely what I needed as a kid and healing to see as an adult. It was incredible to see so many indigenous voices all in one place – in the past, we’ve been told by the publishing gatekeepers that our stories wouldn’t sell. The reception from Native and non-Native readers alike has been wonderful and has proven them wrong. We see many Indigenous books that are bestsellers and win awards. Our books are written by talented people. Our stories are significant and needed in this world.”

“Yes, it was amazing,” Andrea agreed. “Some of the contributors are friends, so it was cool to be able to introduce my characters to their characters, like connecting in another universe. Also, to be able to show – in one anthology – a tiny bit of the diversity of Indian Country? What a gift to readers, especially Native readers who may have been seeing someone from their tribe represented for the first time.”

“It was a really fun project,” Art told me. “We all put our heads together and picked a date and place for the book’s powwow. They asked us to collaborate with the other writers and work each other’s characters into the stories, because when you come to a powwow you’re going to see people. So, in the Trello, they had people putting random information in – like what the weather forecast was going to be on the day of the powwow, who were the head drums, who was the MC, and what the layout of the site was (we ended up choosing a high school in Michigan as the location). We all swapped our stories back and forth so we could read them and make sure we weren’t writing anything conflicting. That part was fun. And I think the stories in that book are a great array of Native stories. There was also a great range of characters. A lot of times, children’s publishers will tell you that kids will only read about younger people. But when you read a Native story for kids, you’ll often see the intergenerational aspect of living – like grandmas and aunties and uncles, because that’s an important part of our lives. Native stories can’t just focus on kids, because that’s not how our community is.”

INDIGENOUS GENRE WRITING

Art continued: “One of the things I’ve been really struck by is that, in the last 5-10 years, there’s been a rise in Native genre writing: like horror, mystery, and romance. Native writers are spreading into different areas, which is exciting to witness.”

With this in mind, I was pleased to be able to interview a few Indigenous genre writers about their projects – namely Cynthia and Andrea, who have already been introduced, alongside Marcie R. Rendon (Ojibwe, White Earth Nation), and Sascha Stronach (Māori [New Zealand]).

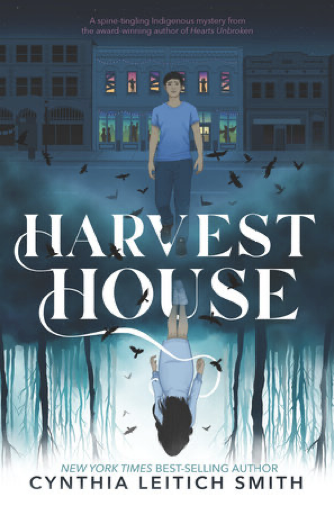

Cynthia’s children’s, middle-grade, and YA books include a few that appeal to genre readers. Aside from Sisters of the Neversea, a good example of this is her upcoming YA ghost story, Harvest House. As Cynthia herself put it, “It’s an Indigenous ghost story following Hughie Wolfe, a theater student. When the school’s Fall play is cancelled due to budget cuts, Hughie decides to volunteer at a Halloween haunted house fundraiser. One problem: It’s actually haunted. There’s a bit more to it than that, though – a sweet romance, a dive into HS journalism, unpacking the ‘Indian burial ground’ trope, and the crisis of murdered and missing indigenous women – with an emphasis on ‘missing’ and the role of the news media.”

Andrea is similarly known for her work in children’s literature, but has made a real splash in the horror genre with her YA debut, Man Made Monsters.

“Man Made Monsters is nearly my life’s work,” Andrea told me. “I started writing the collection’s stories twenty-one years ago. I always enjoyed writing them, even when they left me broken because of how things ended up working out, or not, for the characters. Also, from the get-go I was told I wouldn’t be able to sell a short story collection, so in some ways the manuscript was absolutely not written with the market in mind. If I had known when I started I would be covering ten generations and two hundred years of Cherokee history and the assaults on us, that would have been pretty daunting.”

Andrea went on: “I think that, in so many ways, everyday life is a horror story for people who have been marginalized. We’re like, ‘Werewolves? Monsters? Bring them on. I know how to defeat or align with these outsiders. But how do I get affordable healthcare and clean water without having to crowdfund? How do I learn my language when it was lost through kidnapping and ethnic cleansing? How do I live a life not defined by trauma?’ In this way, I think there’s a notable relationship between the horror genre and the Indigenous experience.”

Marcie similarly explores darker themes, but chooses to do so through murder mysteries, namely her Cash Murder Mystery series. “I read lots of crime novels,” Marcie said, “so my goal is to write books that someone will take on a trip and read from start to finish in one go. But there’s a deeper power to Indigenous voices existing in this space. It shows that we’re here, we’re real, and we come from a long line of storytellers with centuries of experience telling our truth. Our stories, even when we write them as fiction, are universal stories of resilience and of love for our people and communities.”

Then there’s Sascha, who writes fantasy inspired by his Māori heritage. His first novel, The Dawnhounds, is up for a Hugo this year (vote if you’re able)! I saw that the novel was originally self-published, and subsequently got re-released by Saga Press, so I asked him about his experience with that.

“I’d been trying to get The Dawnhounds published,” Sascha told me, “but WorldCon was coming to New Zealand and I knew that this was a once-in-a-lifetime thing – I guess it’s a bit silly, but I wanted to be able to walk the floors of the convention as a published author, and time ran out for any traditional publisher to pick it up in time. At WorldCon it won the SJV Award for Best Novel (New Zealand’s highest honor in Science Fiction / Fantasy), and that got it enough of a boost that publishers actually started paying attention to me. We signed with Saga around 9 months after that, and it finally came out in June 2022. The re-release is substantially different than the original – it’s around 30,000 words longer and it reintroduced a number of elements I’d cut from the drafts (because I’d worried they’d alienate an international audience). Saga were very encouraging about taking the story back to its original – much more distinctly New Zealand – voice, and I also had the wonderful Taz Muir sending me all-caps emails of encouragement such as ‘THE AMERICANS DO NOT NEED TO UNDERSTAND IT; THEY CAN WORK IT OUT VIA CONTEXT CLUES.’”

“Regarding brainstorming and world-building,” Sascha continued, “there wasn’t actually that much required. I wrote the first draft in 2013–2014, when I was living between Surabaya and Kuala Lumpur. That part of the world has been pretty core to the books from day one … I remember flying into Singapore at sunset and there was a line of container ships backed up all the way to the horizon, vanishing into the setting sun. You don’t really understand the scale of these cities from the ground, but those ships took my breath away. After I returned to Aotearoa in 2015 I set the book down for a few years, then came back to rewrite it around the same time I was on a journey to reconnect with my whakapapa Māori while also coming to terms with my queer identity. The earlier drafts were relatively neutral around police work, but for me a major incident during the rewrites was the Auckland Police seriously assaulting a trans woman called Emmy Rakete for protesting during the Pride Parade. In subsequent years there was a push to ban police from Pride, but the New Zealand media painted the queer community as crazy for having an issue with the ‘nice cops who did nothing wrong.’ I felt gaslit and furious at the cops, but I had a cop book in front of me, so I let my rage change it.”

I then found myself curious, what was Sascha’s process for infusing The Dawnhounds with Māori tradition and inspiration? “While I didn’t actively incorporate te ao Māori into earlier drafts,” he told me, “I think it crept in anyway. For me one of the great joys of Māori culture and society is its focus on connectivity – Te Reo Māori has eleven pronouns just to articulate the possible connections between speaker and listener. I was also reading a lot about traditional Māori restorative justice, about how our ancestors practiced jurisprudence in a way the modern world is only just now coming around to. There’s this extremely violent NZ Western called Utu that translated the titular word as revenge, and to this day that’s how most people will translate it. However, it can just as easily mean compensation or repair – it’s a duty to balance the scales, and in many cases a pathway to healing. All of this was coming together into this particularly Māori idea of how we relate to each other in unjust spaces, what we owe each other when there’s so little to give, how we can build a just society while the walls are tumbling down. During the 2017 edits I put all this in explicitly, then chickened out and cut it, then ended up adding it back in for the 2022 edition based on encouragement from Saga.”

“The sequel to The Dawnhounds will be The Sunforge,” Sascha added, “which comes out in May 2024. It’s … a pretty big jump in complexity? We’re talking Gideon to Harrow here. Nobody ever got mad at me for lacking ambition, least of all my editor, who I hope is being adequately compensated for putting up with me. It definitely is a stressful story that hits some big, difficult beats. In particular, I found myself diving into my grandmother’s experiences with genocide in the Ottoman Empire then in Greece under Nazi occupation – these books are about people trying, and not always succeeding, to endure the very worst the world can throw at them. I grew up around a woman who would scream at night and who, after the war, fell so in love with an avowed pacifist that she travelled all the way to New Zealand at his side. There is a darkness to book 2 that has done well with beta readers, but I do worry it might rub some readers the wrong way.”

INDIGENOUS POETRY

Sascha then told me about the role poetry has played in his prose: “I came to prose via poetry, because poetry cannot afford to mess around – each word and piece of punctuation must be perfectly chosen. Flash fiction naturally felt like the next best place to go. I remember seeing people trying to cram 100,000-word novels into 1,000-word stories and realizing how very particular the art form was, how underappreciated. You can’t just do that – if you’ve got 1,000 words you write to 1,000 words and each one needs to count. You’re not trying to tell a story as much as capture a moment, a fire, an ache. I still consider poetry my first love, though, and have gotten back into it in the last year.”

Kim (introduced at the beginning of this article) writes across all children’s literature age groups, and her debut picture book, Just Like Grandma, is written in lyrical form. She similarly found her way to prose through poetry … but her journey began much earlier, in grade school. “I wrote my first poem in the first grade,” Kim said. “It was raining that day, and I was filled with so much emotion that I felt compelled to write about it. On one of our class worksheets, I drew a picture of a girl standing under an umbrella and wrote a poem next to it. When my teacher returned it, she told me that she liked my poem – it made her feel something. That was the first time I ever really saw the power of words. I didn’t start writing Indigenous poetry until I was an adult.”

Heid Erdrich (Obijwe), on the other hand, has built her whole career on poetry. Her most recent collection, Little Big Bully, won the 2022 Rebekah Johnson Bobbit National Prize for Poetry. “Stories, in all their forms, have always been a part of my life,” Heid told me. “Our Dad loved poetry – he recited from heart and taught us to memorize poems as well. We loved books, but had few in the house. However, one was a volume of poems for children, which we treasured.”

“My most recent book came quickly after a few years mulling it over. It was extraordinarily difficult to write, and I did so in a rush. Maybe like pulling off a bandage! Perhaps that was because it was often personal in a way my poetry isn’t usually written. In Little Big Bully, I consider abuse and power and how what we see as children can injure us even if we don’t experience harm. It is about the way women of my cusp Boomer/Gen X endured a lot of harassment and assault. It then takes those themes and amplifies them in poems about politics and the environment as well as realities of life for Native people.”

INDIGENOUS NONFICTION

Native storytelling stretches from fiction and poetry to nonfiction as well. It’s important for readers, both young and old, to be educated about genocide, ethnic cleansing, and the aftermath. If not, hatred is easier to perpetuate and history becomes far more likely to repeat itself. And it’s vital to remember that Native history starts before colonization, and has continued all this time – in other words, Indigenous people don’t exist in a snow globe, forever frozen in the 16th-19th centuries. With this in mind, I was glad to have been able to talk to Joseph and Art about their nonfiction projects (both authors were introduced in the KidLit section).

“Of all my projects,” Joseph told me, “the one I’m most proud of is the book Code Talker. It has been surprisingly successful, recently chosen by TIME magazine as one of the 100 best books for young adults of all time. But its success is not what makes me proud of this book, which I hesitate to call ‘my’ book. It is the men whose stories I told – or, rather, retold in the framework of historical fiction. Those Navajo code talkers were true American heroes and role models. Sent to boarding schools as kids, they were forbidden from speaking their own language. As adults, they were recruited by the Marine Corps during World War II, and asked to use that same forbidden tongue to create an unbreakable code to send radio messages. Their success and their courage are both inspiring and an example for the world of how every culture needs to be respected. I worked closely with a number of Navajo code talkers while writing the book, and everything I wrote was carefully reviewed and vetted by the Navajo Code Talkers Association.”

Joseph also has an upcoming middle-grade nonfiction book titled Of All Tribes, which documents the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz by Native Americans.

“My new non-fiction book took me 4 years to write,” Joseph told me, “and at least 20 years to learn enough to be able to write it. And although I never took part in the occupation, many people I know were there. Some of them were close friends, such as Peter Blue Cloud. Many of them have now passed on, but I was fortunate over the past two years to be able to interview several of the main players in the takeover who were willing to participate. I am so grateful to them – especially Adam Fortunate Eagle and Dr. LaNada Warjack. I believe that people of all ages should learn about the Native takeover of Alcatraz. It is a story that has to do with – as I try to point out – more than just the year and a half of Indigenous activists controlling a former prison island. It has everything to do with the past and present treatment of Native people in this country, and the deep effects that are still being felt throughout this nation.”

Art, on the other hand, got his start as an author by writing a middle-grade fiction book on lacrosse and its Native origins. The book, titled The Creator’s Game: A Story of Baaga’adowe / Lacrosse, is a good example of using storytelling to present educational elements.

“The publishers wanted a textbook,” Art told me, “but I knew that, when I was younger, I would’ve wanted a story instead. So I wrote a story about lacrosse while also covering all the required educational elements. And I was able to convince the publishers to hire a Native illustrator rather than include a bunch of fuzzy black-and-white photos. I suggested Robert DesJarlait, a friend of mine here in Minnesota, and we collaborated on the book together. I wanted kids to be able to have fun learning about the history of lacrosse, rather than me throwing a tome at them.”

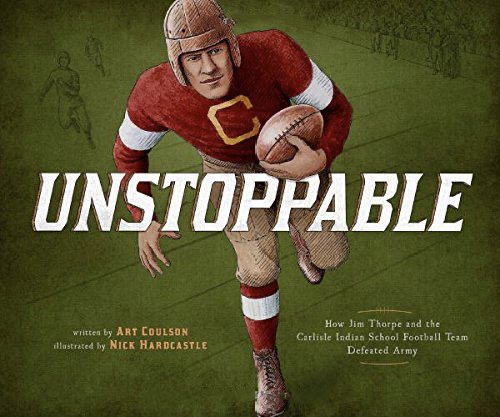

“Around five years later,” Art continued, “I was asked to write another story called Unstoppable – this time for younger readers, with the story covering Jim Thorpe and a very special football game that took place back in 1912. What happened was, the football team from Carlisle Indian Industrial School took the field against the U.S. Military Academy, with sportswriters calling the game a ‘rematch’ of sorts, pitting the descendants of U.S. soldiers and American Indians against each other. But the story is about more than a football game.”

Carlisle Indian Industrial School, created by the U.S. Army, took Native children from their families and effectively tried to brainwash them – they received English names, had all their hair cut, and were forbidden from speaking their own language or practicing their own religions. It was all an experiment to see if one could “kill the Indian to save the man,” as the school’s founder put it. Many children died of mistreatment, malnourishment, and disease – and Carlisle was only one of 150 boarding schools across the U.S. doing this. Unstoppable is a story about football, yes … but it’s also about ethnic cleansing, packaged in a way that is both educational and understandable to children.

A FINAL WORD OF ENCOURAGEMENT & ADVICE FOR NATIVE PEOPLE

We’ll end on some advice from Joseph, the eldest of our group:

“My advice for emerging Indigenous voices is simple. You have to be determined. There will always be people who tell you that you’re not the right fit or that you should just give up. I’ve been told by editors at literary magazines to give up and do something more useful, like coach Little League baseball, or that I shouldn’t even bother because everything great has already been said by Dostoyevsky. Remember, for years non-Native people have tried to tell our stories, both fact and fiction. Some have done so in a fairly honorable way, but others have been anything but honorable. Make no mistake, you are needed. And don’t think you need to focus solely on the past or shy away from modern injustices to create work that is meaningful and necessary. Books like Angeline Boulley’s amazing Firekeeper’s Daughter and Morgan Talty’s painfully brilliant Night of the Living Rez remind us of that.”

“And for non-Indigenous writers,” Joseph continues, “my advice is to read widely and without prejudice. Don’t assume that one form is more noble or important than another, just as we should not assume that any one person is more important than any other. Find writers whose work you admire, who move you with what they have written, and then look carefully at how they write, how they phrase things, how they create situations and images, and how they use the tools of their craft. And finally, never think that you know everything, because you don’t. No one does.”

Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee citizen) is a NYT bestselling author and was named the 2021 NSK Neustadt Laureate. Her novel Hearts Unbroken won an American Indian Youth Literature Award. Her recent books include Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids, as well as Sisters of the Neversea. Her debut tween novel Rain is Not My Indian Name was named one of the 30 Most Influential Children’s Books of All Time by Book Riot. Her 2023 release is Harvest House, a YA novel and Indigenous ghost mystery. Cynthia is the author-curator of Heartdrum, an imprint of Harper Children’s, and was the inaugural Katherine Paterson Chair at the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program.

Marcie R. Rendon is an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation, author, playwright, poet, and freelance writer. Also a community arts activist, Rendon supports other native artists / writers / creators to pursue their art, and is a speaker for colleges and community groups on Native issues, leadership, and writing.

She is an award-winning author of a fresh new murder mystery series, and also has an extensive body of fiction and nonfiction works. The creative mind behind Raving Native Theater, Rendon has also curated community created performances such as Art Is… Creative Native Resilience.

Kim Rogers is the author of Just Like Grandma, illustrated by Julie Flett; A Letter for Bob, illustrated by Jonathan Nelson, is planned for summer 2023; and I Am Osage: How Clarence Tinker became the First Native American Major General, illustrated by Bobby Von Martin comes out in winter of 2024, all with Heartdrum. Se is a contributor to Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids (Heartdrum, 2021). Kim is an enrolled member of Wichita and Affiliated Tribes and a member of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. She lives with her family on her tribe’s ancestral homelands in Oklahoma.

Sascha Stronach is a Maori author from the Kai Tahu iwi and Kati Huirapa Runaka Ki Puketeraki hapu. He is based in Wellington, New Zealand, and has also spent time in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore, which have all inspired parts of the fictional worlds he creates. A former tech writer, he first broke out into speculative fiction by experimenting with the short form. The Dawnhounds, his debut novel, won the Sir Julius Vogel Award at Worldcon 78, and is eligible for the 2023 Hugo’s.

Andrea L. Rogers is a writer from Tulsa, Oklahoma and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. She graduated from the Institute of American Indian and Alaskan Arts with an MFA in Creative Writing. Currently, she is splitting time between Fayetteville, Arkansas, where she is a PhD student at the University of Arkansas and Fort Worth, Texas, where her family lives. She is a member of the Horror Writers Association and a member of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). Andrea is currently revising a middle grade mystery, writing an adult literary horror novel, and working on a series of picture book manuscripts.

Art Coulson, Cherokee, was born in Honolulu, where he lived for his first 7 months. Art and his family moved often, sometimes more than once a year. His first children’s book, The Creator’s Game, a story about a young lacrosse player, was published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in 2013. Since then, he has published a number of other books and short stories for children. His most recent book, Chasing Bigfoot, was published in 2022 by Reycraft Books.

Heid E. Erdrich (Ojibwe) is the author of numerous collections, including Little Big Bully (Penguin, 2020); Curator of Ephemera at the New Museum for Archaic Media (Michigan State University Press, 2017) and four other collections. She edited New Poets of Native Nations (Graywolf Press, 2018). Heid has received two Minnesota Book Awards, as well as fellowships and awards from the Library of Congress, National Poetry Series, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, Loft Literary Center, First People’s Fund, and others. Heid has produced short films and installations, and curated dozens of exhibitions of Native American art.

Josheph Bruchac, Abenaki poet and storyteller, was born in Greenfield Center, New York. He earned his BA from Cornell University, MA from Syracuse, and PhD in comparative literature from the Union Institute of Ohio. He is the author of more than 170 books for adults and children, including Tell Me a Tale: A Book About Storytelling (1997); The First Strawberries: A Cherokee Story (1993); Keepers of the Earth (1988), which he coauthored with Michael Caduto; his autobiography, Bowman’s Store: A Journey to Myself (1997); and novels for young readers such as Dawn Land (1993) and The Heart of a Chief (1998).