By Alyse Mgrdichian

When people think of storytelling, they usually think of words – like how we tell bedtime stories or write fiction / nonfiction narratives. We also have films and videogames, which add visual and auditory elements into the mix. However, we’re not going to talk about those forms of storytelling today, as interesting as they are. Today we’ll be focusing on another method entirely – artwork, and in particular, graphic novels.

So, what are graphic novels? Despite their rising popularity, there isn’t really a set definition for them. However, the general understanding is that they are stories set up in comic-strip format and published as an official book, rather than as serialized comics.

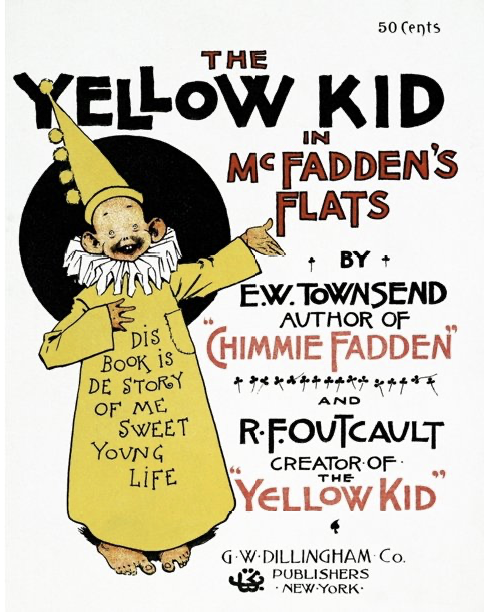

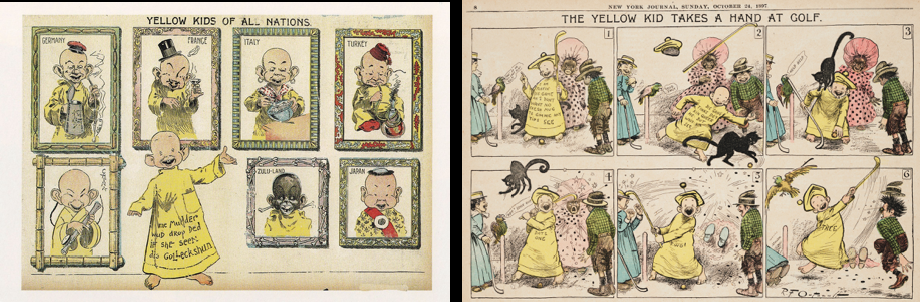

With this in mind, comic strips are, unsurprisingly, the genesis of graphic novels. The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats is generally credited as the first existing strip, debuting in 1896. Originally published in New York World, The Yellow Kid was certainly a product of its time. Its pages were filled with racial stereotypes and caricatures, although it’s said that its purpose was to make wealthy readers more sympathetic toward those who were poor, since the story focused on the plight of immigrant children living in the tenements of New York (with the Yellow Kid himself being an Irish immigrant).

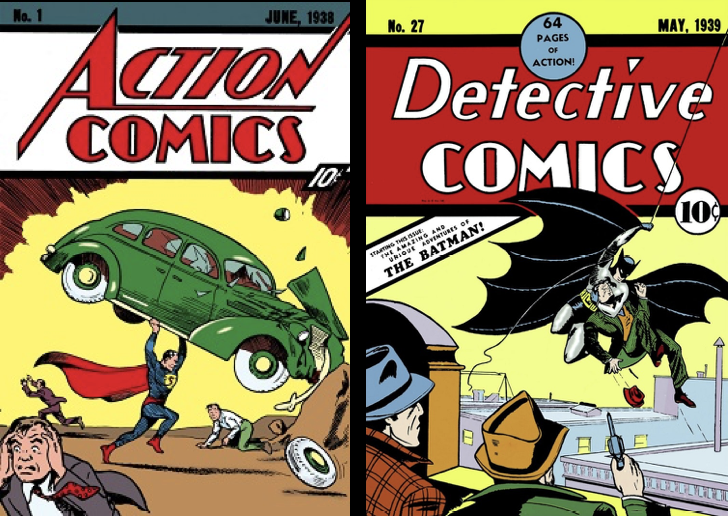

After The Yellow Kid came a heavy flow of comic strips, such as Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905), Mutt and Jeff (1907), Little Orphan Annie (1924) Blondie (1930), and Flash Gordon (1934). Comic strips continued throughout the 1900s and early 2000s (e.g., Garfield, Peanuts, Calvin & Hobbes, etc.), but something entirely new had evolved from them – comic books. Superman made his debut in 1938, and Batman was introduced less than a year later, both to tremendous success. 1938–1956 became known as the “Golden Age” of comic books, with each month bringing millions of sales.

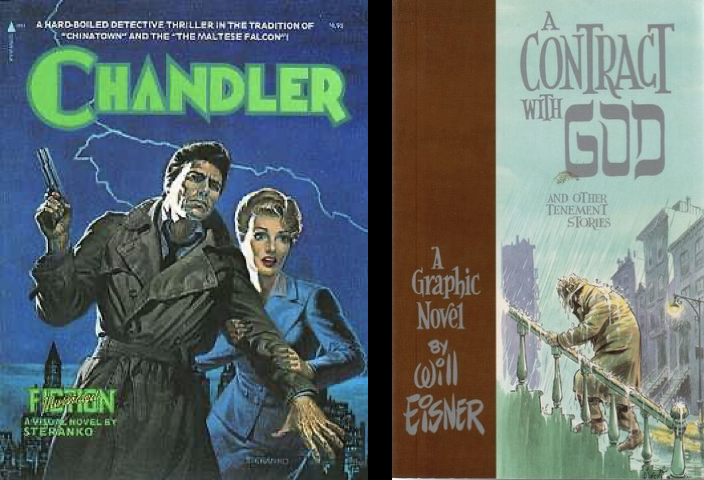

While comic books have persisted till this day, their reception has become modest in comparison. However, comic books are what directly birthed graphic novels. 1976 brought detective thriller Chandler: Red Tide, one of the first publications to ever market itself as a graphic novel. Two years later came A Contract with God & Other Tenement Stories, a collection of Jewish short stories that marketed itself similarly. There is, as always, more to it than that – but we’ll stop the history lesson here, since we’ve covered the basics.

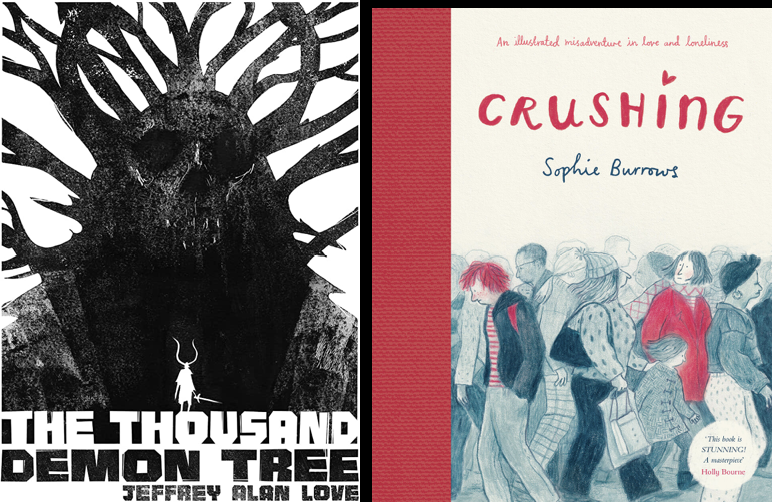

So, where do we find ourselves now? Graphic novels will, most of the time, have text that works alongside pictures to tell a story. Very rarely will we see a graphic novel without any words, but it is certainly possible – such as in The Thousand Demon Tree (a personal favorite of mine) and Crushing.

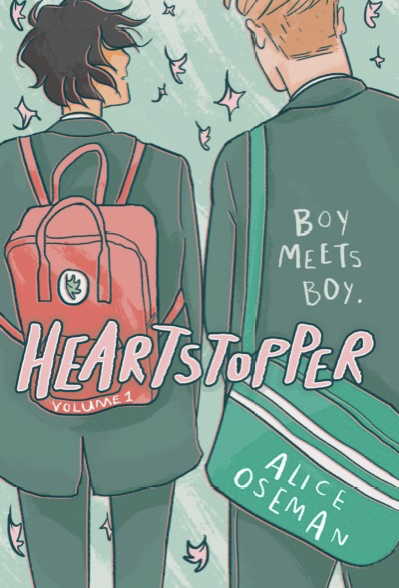

Our current age of graphic novels has also brought fresh distinctions between children’s, YA, and adult publications, with graphic novels becoming increasingly popular across all age ranges. For example, popular publications for children include The Babysitters Club, American Born Chinese, and Wings of Fire – the books’ themes tend to center around adventure and growing up. Some popular YA graphic novels, on the other hand, include Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me, The Girl from the Sea, and Heartstopper, which tend to focus on romance.

With Heartstopper in mind, it’s important to note how the graphic novel industry has fundamentally changed because of digital webcomics (which Heartstopper once was). The industry has opened up opportunities for more stories to be told, with publishers beginning to take interest in digitally acclaimed material. After all, it’s easier to market a new book if it already has a loyal online fanbase. This trend is similar to what we’re seeing with self-published books being picked up by traditional publishers for re-release – it opens the door for fresher, riskier stories that otherwise may not have been chosen.

It’s also worth noting that superheroes, in all their forms, have persisted and evolved. Nowadays, young readers are being introduced to graphic novels about characters like Shuri (Black Panther), Miles Morales (Spiderman), and Ms. Marvel … role models who, in one way or another, kids can look up to, relate to, and emulate. Across all age groups, there’s now more diversity and relatability to our heroes and villains than ever before (regardless of whether it’s a “superhero comic” or not), which I think is a huge step in the right direction.

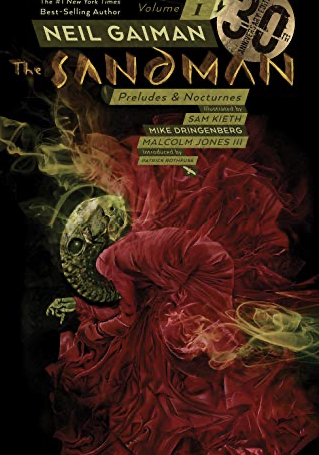

But what about the adult stuff? The Sandman, Persepolis (nonfiction), Watchmen, V for Vendetta, The Umbrella Academy, and Maus (nonfiction) are just a few examples of highly popular adult graphic novels. And since they’re for adults, they can afford to be more violent and suggestive than the children’s & YA publications, which some folks prefer. An example of this is the various Batman graphic novels that have come out, which abandon their signature campiness and embrace a gritty noir tone instead.

There is educational potential for adult graphic novels as well … not to say that there isn’t the same potential in children’s publications, but (as previously mentioned) adult books can dive a little deeper into distressing themes. In the case of Maus and Persepolis, Maus is about a father’s experience surviving the Holocaust, while Persepolis is an autobiographical look at a woman’s life in Iran after the Islamic revolution. I’ve seen both books assigned as homework in high school and college level courses, which just goes to show the variety of ways in which we can learn. My day job is at a bookstore, and I’ve even seen high schoolers ask for the graphic novel version of Anne Frank’s diary so they can read it for fun – they want to learn, and have found an engaging way to do so.

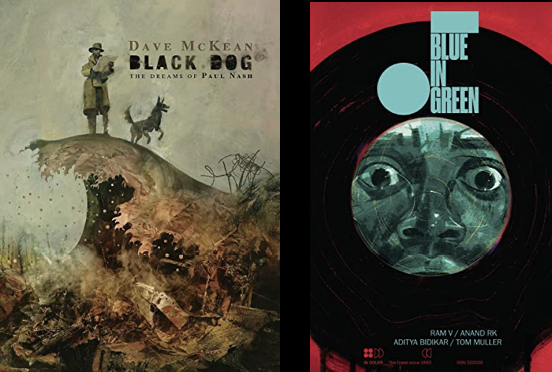

In terms of my own taste, I personally really enjoy alternative / underground graphic novels, which tend to be a little more artsy (and are usually standalones rather than series) – such as The Thousand Demon Tree, which I mentioned before, alongside Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash and Blue in Green.

And here we are, at the end already. While writing this conclusion, I wondered how I should finish – perhaps I could give encouragement to aspiring graphic novelists, or predict future trends, or maybe I could give a list of upcoming releases to look out for. However, while trying to draft those thoughts, I was stopped cold by a memory.

After my grandpa died, I was rummaging through his things to help clear them out, and I found an American newspaper he had kept for more than seven decades. It was published the day after the atomic bomb dropped on Japan in WWII – and in that newspaper was a comic strip showing racist caricatures of anonymous Japanese generals. Art has the power to uplift, but more often than not it’s used as a quick jab, a cheap insult. Looking at the strip, I felt sad and angry and overwhelmed. Between 129,000 and 226,000 people, mostly civilians, had died … and a newspaper was trying to use art to further dehumanize them, to elicit a chuckle and a shrug from its readers. While it’s true that we should create boldly and with confidence and purpose, we need to create with humanity too. Never be afraid to look deeply within yourself and in others, and never lose your capacity for empathy. In other words, don’t let your art devolve into a thoughtless chuckle and a shrug. The act of reflective creation is a big task (a rebellious one, even), but it’s worthwhile – I promise.