Nowhere Man by Miguel Mejides

“Miguel Mejides is a Cuban novelist and storyteller who has been recognized as a major voice in Cuban literature.” —Brown University

There are people who need to go against the grain but I’m not going against anything. Perhaps everything stems from the great handicap which life has given me: I’m cross-eyed. Ever since I’ve been able to reason, since the first time I was able to contemplate my image in a mirror and saw my own eyes, I told myself I was a man meant for silence, for meditation, a man made to work at smiling, fated to take long walks through the city I choose for my solitude.

My mother, thank God, always knew about the shadow of the silent songbird that surrounded me. Likewise, she understood my decision to leave my hometown to go to Havana and find work. I’ve never been able to forget her, bidding me farewell at the train station with her linen handkerchief waving between the smoke and her saintly smile, which never left her, not even in death.

Even though it’s rained a lot these years, until very recently I could still give myself the pleasure of contemplating Havana through the same lens as when I first glimpsed it in January 1990. Back then, Havana still retained that halo of light and mystery. My bus came in on the old central highway, continued past Virgen del Camino, and straight through the disastrous streets of Luyano. At the end of my journey, I was awed by the statue of Marti in the Plaza de la Revolucion and the sparkling Ferris wheel in the amusement park in front of the bus terminal.

I’ll never forget the taxi that took me to Infanta 234; it was a mandarin-colored De Soto, with the coat-of-arms from an ancient Spanish province affixed with the number 13. The driver was a little old man with an Andalusian accent and a multicolored hat.

“That’s the place.” I remember the stains on his teeth that flashed when he talked. As I paid him, he betrayed a certain anxiety about my eyes. “Buddy, buy yourself some dark glasses,” he told me.

FromHavana Noir, edited by Achy Obejas, Akashic Books, akashicbooks.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

“Cuba has produced an author capable of understanding science fiction by writing it like it’s rock and roll. Yoss is a thoughtful author who simply seems to understand his work and science fiction better than many of us.” —Electric Literature

Super Extra Grande

by Yoss

translated from the Spanish by David Frye

“Boss Sangan, sludge al frente and a la derecha, ten centimetros knee,” Narbuk peevishly announces through my ear buds.

His voice reminds me unpleasantly of a screechy old machine in need of a lube job. But that’s not the worst of it. Worst is, he seems to go out of his way to mangle the grammar and syntax of the Spanglish language, stubbornly dropping prepositions and mutilating verbs like he’s doing a bad impression of a native in a third-rate holoseries.

Regardless, the Laggoru can monitor my progress from a distance, and the radar he’s using gives him the overview of the situation that I want.

The spot he’s guiding more towards flashes blue on the 3-D virtual map of the tsunami’s intestines, which I can see super-imposed on the upper-right-hand corner of my helmet’s visor. Doesn’t look promising to me, but in the lower-left-hand corner I see Narbuk’s face, looking like a hypertrophied iguana, insisting, “Boss Sangan, please mira, check. Ves now. Si the damn bracelet of the gobernador’s spoiled wife be there, us probablemente leave.” For variety’s sake, he now starts in on the complaints. “Agua here smell muy strange despues del morpheorol y el laxative. Hoy not be buen dia for el tsunami bowel cleanse.”

You have to prep before you can operate. In this case, to tranquilize the “patient” before I started exploring its innards, we dissolved enough morpheorol in the water to sedate a small city for a whole week.

Good thing morpheorol doesn’t really affect humans.

From Super Extra Grande by Yoss, translated from the Spanish by David Frye, Restless Books, restlessbooks.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Heretics

by Leonardo Padura

translated from the Spanish by Anna Kushner

“As Cuba’s greatest living writer and one who is inching toward the pantheon occupied by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, Padura may well now be untouchable.” —The Washington Post

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

fsgbooks.com

It would take Daniel Kaminsky many years to grow accustomed to the exuberant sounds of a city built on the most unwieldy commotion. He had quickly discovered that everything there began and ended with yelling, everything sputtered with rust and humidity, cars moved forward amid the wheezing and banging of engines or the long beeping of horns, dogs barked with and without reason and roosters even crowed at midnight, while each vendor made himself known with a toot, a bell, a trumpet, a whistle, a rattle, a flageolet, a melody in perfect pitch, or, simply, a shriek. He had run aground in a city in which, on top of it all, each night, at nine on the dot, cannon fire roared without any declaration of war or city gates to close, and where, in good times and bad, you always, always heard music, and not just that, singing.

At the beginning of his Havana life, the boy would often try to evoke, as much as his scarcely-filled-with-memories mind would allow, the thick silences of the Jewish bourgeois neighborhood in Krakow where he had been born and lived his early days. He pursued that cold, rose-colored land of the past intuitively from the depths of his rootlessness; but when his memories, real or imagined, touched down on the firm ground of reality, he immediately reacted and tried to escape it. In the dark, silent Krakow of his infancy, too much noise could mean only two things: it was either market day or there was some imminent danger. In the final years of his Polish existence, danger grew to be more common than merchants. So fear became a constant companion.

From Heretics by Leonardo Padura, translated from the Spanish by Anna Kushner, Farrar Straus and Giroux, fsgbooks.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

A Corner of the World

by Mylene Fernandez-Pintado

translated from the Spanish by Dick Cluster

“Fernandez might most fittingly be described as a literary guardian of Cuba, a collector of her island’s own stories of loss and longing and, also, of love.” —L.A. Review of Books

The mechanic poked his head out from under the car to berate me for being stupid, for letting myself get taken by the mechanic before him, who had also berated me for falling into the trap of the one before that. As always in such situations, I had two choices. One was to wholeheartedly agree, which would provoke a dialogue. The other was to adopt the shamefaced expression befitting a victim of countless members of the guild. That would lead to a monologue.

My mother’s death had made me the sole heir of a car that, while inadequate by international standards, was satisfactory by our local ones. We are not very demanding in the matter of cars. My “brand-new” 1970 Moskvich was a treasure on wheels.

“Are you a writer?” the mechanic asked.

To mechanics, writers are people with clean hands and lots of money.

To writers, mechanics are people with dirty hands and lots of money.

My mother didn’t leave me any money, but she did leave some things of value: an upright piano and lots of sheet music. Her music. All I can do with the instrument is to put my hands on the keys and have them respond without much conviction. Still, out of all the objects she left that cluster indifferently around me, that piano feels the most my own.

I also inherited a porcelain table setting, silverware that’s truly silver, and linen tablecloths. Also glassware of all sizes and sorts. Endless treasure that have no means of locomotion. We take care of them all our lives, and they almost always survive us.

Also she left me a gaping void of loneliness, at the age of thirty-seven.

From A Corner of the World by Mylene Fernandez-Pintado, translated from the Spanish by Dick Cluster, City Lights, citylights.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

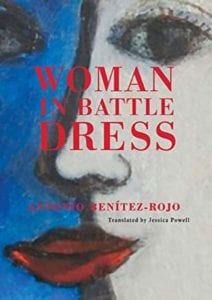

Woman in Battle Dress

by Antonio Benitez-Rojo

translated by Jessica Powell

“A novelist, essayist and short-story writer, Benítez-Rojo was widely regarded as the most significant Cuban author of his generation.” —Amherst College

And so, in three days you’ll disembark in New Orleans. Four, at the most, if the wind fails. As hard as you try to take heart, you can see no reason that you should be any better received there than you were in Cuba. What they know of you in New Orleans is nothing but secondhand gossip spread by travelers from Havana; rumors repeated by sailors and merchants who, hoping to amaze their listeners, turn every drizzle into a downpour, every chicken’s death into a horrifying murder. God only knows what abominations they are telling about you there! If there’s one thing you’re sure of, it’s that the dock will be full of gawkers hurling insults. Some will even spit at you. There’ll be the usual hailstorm of eggs and rotten vegetables. There will even be those who’ll try to pinch your backside or claw at your face. Master and slave, lawyer, barber, shoemaker and tailor, each and every one of them will heap their own guilt and resentments onto you. The saddest part of all is that there are bound to be some good women among the crowd, women who’ll condemn you without even knowing why. Their minds constricted by ignorance and prejudice, they’ll see you only as an indecent foreigner a degenerate; never a friend. How well you know their accusatory cries. They have dogged you from one end of Cuba to the other, from Santiago all the way to Havana. The only difference is that this time they’ll humiliate you in English, and even in French, your own mother tongue. What you fear most, what you’ve begun to obsess over, is that moment when you’ll step off the boat – your first steps onto the dock, exposed to all those stares, those hungry eyes fixed upon you, wishing to strip you bare.

FromWoman in Battle Dress by Antonio Benitez-Rojo, translated by Jessica Powell, City Lights, citylights.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.