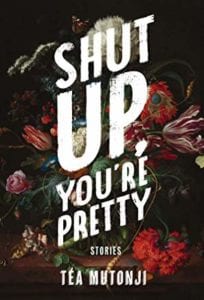

About the Book:

In Téa Mutonji’s disarming debut story collection, a woman contemplates her Congolese traditions during a family wedding, a teenage girl looks for happiness inside a pack of cigarettes, a mother reconnects with her daughter through their shared interest in fish, and a young woman decides on shaving her head in the waiting room of an abortion clinic.

These punchy, sharply observed stories blur the lines between longing and choosing, exploring the narrator’s experience as an involuntary one. Tinged with pathos and humor, they interrogate the moments in which femininity, womanness, and identity are not only questioned but also imposed.

Shut Up You’re Pretty is the first book to be published under VS. Books, a series of books curated and edited by writer-musician Vivek Shraya featuring work by new and emerging Indigenous or Black writers, or writers of color.

Read an Excerpt:

Featured in Aug/Sept 2019 Issue: Fierce Female

“Jolie was my first friend. Her name was actually Jolietta. I shortened it to Jolie upon meeting her. I felt it captured her spirit more, her essence. The name came from a song Mother used to sing when we lived in Congo, where it was hot and mosquitoes didn’t sting because we coexisted with them. “Mommy’s baby, pretty, pretty,” the song went. Mother stopped singing once we immigrated. She stopped doing many things. But I liked that she had given me this—this song so that I could now give it to someone else. And Jolie was in fact jolie: long blonde hair, defined nose, blue in her eyes, roses in each cheek, tall but not defiantly so.

She was the one who introduced me to the park. She was responsible for my popularity and my likability, because she was herself popular and well liked, and I gained her reputation by proximity. But still, I was the girl next door.

Unlike Jolie, I had perfectly ashy elbows and naturally lacked poise, and this was my advantage on Galloway. People could relate to that. As for Jolie, she was simply unattainable. To want a person like her was to want too much from life. To have a person like her was to have everything and, perhaps, too soon.

When we arrived, Jolie was sitting on our doorstep, as though to check that the newcomers weren’t freaks. And then she gave a thumbs-up to a bunch of kids watching from the other side of the roundabout. There was another set of low-rise townhomes, peeling and brown, identical to ours. The thumbs-up meant that we were acceptable, that we had passed some unknown street cred test, and Jolie was both curator and writer of said test.

She introduced herself as we were unloading the suitcases from the taxi. That’s all we had. Suitcases. We were lucky enough that the previous tenants had left behind some furniture and that whoever ran the complex took pity on our poverty and allowed us to claim it as our own.

“Welcome to Galloway,” Jolie said, reaching her hand out to greet my father. As they shook hands, she grimaced a smile at him, stuck her tongue out, and winked. “Can he come out and play?” she asked.”