On a sunny L.A. day in 1975, a young photographer named Hugh Holland was driving up Laurel Canyon Boulevard when he saw something he, and most everyone else, had never witnessed before. Something that made him stop his car and grab his camera. Because, out of the corner of his eye, it looked like one after another golden-haired boys were rising up and floating above the pavement in a fluid, time-stopping arc before disappearing out of sight. In fact, in a drainage bowl below street level, tanned, tube-socked, and helmetless teenagers were launching themselves vertical with nothing more than a wooden deck and a set of urethane wheels. Holland, who had never been on a skateboard himself much less dropped in to an empty swimming pool, was hooked, quickly finding himself at the hub (and oftentimes at the wheel) of the burgeoning SoCal skateboarding scene.

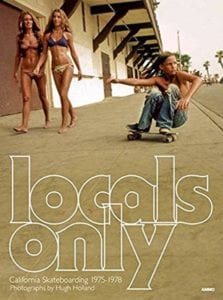

Over the next three years, he documented skateboarders on the streets of Los Angeles, the San Fernando Valley, Venice Beach, San Francisco, and Baja California, Mexico. His resulting photographs have recently been compiled in Locals Only, a large-format photography book from Ammo Books featuring 120 color images of legendary Dogtown and Z-Boys skateboarders along with nameless and shirtless others. Locals Only masterfully captures the daring athleticism of a knee-pad- and sunscreen-less generation in all its tanned and Vanned glory. The book also contains an interview with Holland by editor Steve Crist about the birth of extreme sports, the advantages of recycled movie film, and how a drought changed the face of skateboarding forever. —Dean Hill

photographs by Hugh Holland

edited by Steve Crist

Steve Crist: So, how did you get started photographing the skateboard work?

Hugh Holland: I lived in Hollywood, and in that period I started noticing more and more young skateboarders on the streets and everywhere. I had started photographing them here and there, and I had even traveled down to a small contest in a mini-mall in Torrance that I had heard about. I got a few of my best pictures that first day, actually, so that was a really good start.

The real start, though, was one afternoon in the summer of 1975. I was in my car, driving up Laurel Canyon toward Mulholland, when I noticed a group of kids skating in a drainage bowl off to the right side. They called it the “Mini Bowl.” It was small with very steep sides, and they were going up and down those banks. And out of the corner of my eye, while driving, I could have sworn that they were actually flying. The bowl was mostly below street level, so I just saw the skaters bobbing up and then sinking back out of sight.

I parked the car on a side road and walked down to the bowl with my camera. That was the first time I saw vertical skating. As soon as the skaters saw the camera they perked up. I was immediately welcome. In those days, there were far fewer cameras around, so the camera was my “in.”

So I was welcomed right away, and the kids in Laurel Canyon were my first contacts. I didn’t really catch the skate imaging bug until I went up and made friends with them, and for the next three years—although I traveled all over California—I always came back to the “Mini Bowl” and the other bowl up the street called “Skyline.”

Crist: Did you continue to search out these kinds of informal photo opportunities?

Holland: Usually on the weekends I would go up there to that place, and it wasn’t long before I was branching out to other drainage bowls around the area. The guys would always have a new hot spot to check out. There are a lot of beautiful drainage bowls in the canyons in L.A., Beverly Hills, West L.A., and Santa Monica.

Benedict Canyon had a really big, nice one. Laurel Canyon had a couple, and that was my home base. Those two had the same groupings of “locals” usually, but the groups were fluid, and they kept changing and moving and going places. There was a huge bowl just above the Hollywood Reservoir. It was very big, but not many skaters knew about it, so the locals from the area claimed it all for themselves and called it “Vipers Bowl.”

I had a car, which was useful, and skaters would pile in and we’d go to whatever place was on their radar at the moment for getting vertical: bowls, ramps, and then, of course, the empty swimming pools all over the west side and into the Valley. Eventually I made it as far north as the Bay Area, and as far south as Ensenada, Mexico.

Skateboarders came to these spots from all over Southern California just because they heard about them; somehow they came, one way or another, and that was long before mobile phones and texting. When I think back and recall those times, I think, how did they know where to go? It was amazing, but somehow they always knew. It was information passed quickly along solely by word of mouth from one skateboarder to another.

Crist: How was skateboarding changing in those years from when you started photographing to the time you ended? What was going on?

Holland: It was amazing. Everything changed very fast within those three years.

In ’75 we were mostly in the canyon bowls and started getting out to the many different schoolyards like Kenter and Paul Revere. Schoolyards were great because they had these asphalt banks, which were perfect for skating, and large flat areas, too. By ’76 the scene was moving to empty swimming pools, and then, after that, the skate parks started to appear, and there were bigger and bigger organized contests. In ’77, commercialism started to come into the new sport.

When I look at the pictures that I took then, 35 years ago or so, I can right away tell which ones are from ’75, from ’76, and from ’77, just by the way they’re dressed and the surroundings and what kind of skating they’re doing. There was a big shift in the three years, and a big part of the sport became commercial really fast. Manufacturers and skate parks and insurance companies moved in. The equipment came: helmets, knee pads, elbow pads, shoes, anything you can imagine that a person might wear or use when he’s skateboarding—just like any other sport. When I started recording them, there were a lot who were barefoot and without helmets (not that that is a good thing for safety, but it looked good in pictures), but by the end of ’77, those were rare, and most were all trussed up in gear.

Today, besides the sports professionals and “extreme athletes,” you can still see a lot of neighborhood kids out skateboarding, and you also see ordinary adults out skating on the streets just for transportation. Everybody’s skateboarding now, but back in the early days it was pretty much just the teenagers, mostly male, and they were out discovering brand new thrills.

I came onto the scene just after the introduction of the urethane wheel, which made it possible to go vertical, and that became a really, really exciting thing—to, as they said, “get air,” or “go for coping” in the dry swimming pool.

There was a drought in ’76–’77 in California, so many swimming pools had to be emptied because there was not enough water. That provided tons of new places to get vertical, and so they were all out looking for empty swimming pools and climbing over back fences. I was there too, lying on my back on the bottom of a pool.

So those two things—the invention of the urethane wheel for traction and the drought providing empty pools and basins—made those years perfect for the beginning of a radical and exciting sport and the visuals that it engendered, which is where I came in.

From “Interview with Hugh Holland” by Steve Crist, Locals Only: CaliforniaSkateboarding 1975–1978, photographs by Hugh Holland, © 2010 Ammo Books, www.ammobooks.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

FromBrooklyn’s own Soft Skull Press is Life & Limb (2004), a collection of writing about the gravity-defying, law-breaking, one-upping, double-dog-daring, raw-skin-meets-pavement counter culture that is skateboarding. Contributors include Mark Gonzalez, Ed Templeton, Michael Burnett, Scott Bourne, and Angela Boatwright. Introduction by Jocko Weyland, edited by Justin Hocking, Jared Maher, and Jeffrey Knutson. www.softskull.com.