By the eighth month of their pregnancy, two more neighborhood teenagers and an elderly couple had died. A young gangster was killed on his way home from school. He died because he was flashing his Hazard signs to a convoy of cars that drove by with shouts of “Maravilla rules!” When they drove past again, the young Hazard kid stood his ground by proudly showing his signs, but this time the Maravilla boys replied by cutting him down in a volley of gunfire.

The other death was of a sixteen-year-old girl, known throughout the barrio as La Sacred. Having spent most of her life in and out of different psychiatric wards around Los Angeles and Orange County, La Sacred was a notorious loca. She was visiting her cousins who were celebrating a quinceañera in Geraghty. It was during the reception after mass that the party was interrupted by a gang of homeboys from Jim Town. One of them respectfully asked to speak to his girlfriend, La Sacred. When she walked out onto the street with him, they shot her and then opened fire on the rest of the crowd. Cars jammed with Geraghty homies sped off in hot pursuit of the invaders, but the lead car crashed into a parked truck, holding up the posse.

Old Taíta Fonseca was killed for complaining about a gang of cholos who were parking their lowriders in front of his house. Rigged up with the loudest speakers they could find, the cholos would sit there with their girlfriends, blasting the music. When the bass made everything in his house rattle and vibrate, Don Taíta went out and yelled at them to turn it down, threatening that if they didn’t, he would call the police. The cholos just turned it up louder. Infuriated, Don Taíta got his hose and began spraying water through the window of one of the cars. The two homeboys inside got out and immediately shot him down. Old Taíta died in a puddle of water in the middle of his front lawn, where he and his wife had tended their rose garden. She witnessed the whole thing from her wheelchair, peering out of their living room window. The two of them had lived in this four-bedroom house for over fifty years.

Mrs. Fonseca wouldn’t let go of her beloved husband’s cold hands. When they lifted his body up into the truck, she lost her breath, letting out a feeble and desperate cry for the man she had known her entire life. That night Micaela, Beatriz and Carmen brought her to the Center where Paca, as always, was waiting with her camera. After two days, Mrs. Fonseca realized that her husband was never going to come home, so she decided to die. She stopped eating and drinking, refusing to allow anything to enter her body. She didn’t speak, cry or sleep. For exactly nine days, enough time to pray a novena, she sat motionless with her eyes open, looking out the window by day and waiting into the night for Don Taíta to come back for her.

“It won’t be long now, my love” were her last words.

On the morning of the ninth day, Reina brought her a glass of milk and found her dead in front of the window, still sitting with her eyes open and the hint of a smile on her lips. In the last breaths of her life, somehow Mrs. Fonseca had risen from her bed, opened the window in the living room and sat down to watch the world outside, where she saw the trees, the garden flowers, the rose bushes and, perhaps, an old gentleman walking through the gate to come get her on that sunny morning.

Felícitas, Beatriz, Filomena, every woman from the Federation understood the bond of love between the Fonsecas. The two teachers, Mrs. Marbel and Mrs. Kochart, donated money to have the old couple buried at Calvary Cemetery. At the funeral both women confessed that they had known the couple for years, but neither of them had ever learned their names.

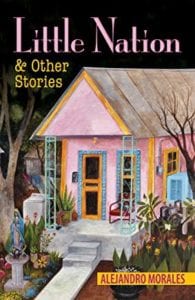

From Little Nation and Other Stories by Alejandro Morales, Arte Público Press 2014, artepublicopress.com. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.