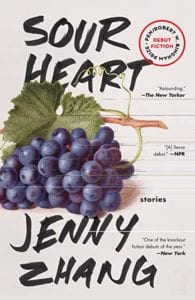

The first publication from Lena Dunham’s Random House imprint Lenny, Sour Heart is a brilliant, moving portrayal of the struggles of Chinese girls coming of age in America.

Lenny Books

randomhousebooks.com

Shelf Unbound: Your young girl characters struggle with their families’, particularly their mothers’, expectations that they stay tightly connected to the family and their Chinese culture while also forging their way as new Americans with an opportunity, even a responsibility, for a better, bright future. Can you talk about this conflict?

Jenny Zhang: It’s a classic conflict for young people growing up—who are you? Who do you want to become? Who do other people want you to become? There are plenty of stories about adolescent rebellion, turning away from your family and not giving in to societal pressures, but what if you love the people whose values you are rebelling against? What if you feel deeply indebted to the people who raised you? What if you grow up in a society that doesn’t expect anything of you anyway because you’re not a white, native-born English speaker? The girls in these stories come from families who have lost so much—back in China and now in the States—and that loss can be disfiguring, difficult to rebound from. But at the same time, these girls are not exactly finding safe refuge in mainstream American society. When I was a girl I borrowed and tried to co-opt narratives that were not my own in looking for stories about growing up. I was drawn to narratives about the alienated outsider, big weirdos who have to find their own way—but often in these narratives, there was pure contempt for family, or simply disinterest or coldness. I wanted to convey a kind of warmth, a kind of intense love. What happens when you love your family too much but you’re still a big lonely weirdo? What happens when your family loves you too much but they are from the old country, still entrenched in third world values even as their own kid is now facing first world problems? How do people who have struggled to survive their whole lives relate to their children who are living comparatively sheltered lives? At the same time the children in my stories are not totally sheltered or protected. They have a whole set of dangers that are illegible to their parents. These were the questions that occupied me in writing these stories. I wanted to approach these massive dilemmas with humor, curiosity, and empathy.

Shelf Unbound: The families in these stories are linked by having shared a cramped, squalid apartment with each other after immigrating from China. Why did you choose to link them?

Zhang: It’s a group portrait of a very specific cohort of Chinese American immigrants who came as students during the second wave of immigration from mainland China after the Cultural Revolution ended. You know how sometimes the news will report on some seemingly-random town in Minnesota that has the second largest population of X ethnic group outside of actual country of origin? I wanted to take that story out of the realm and gaze of journalism and say something interesting about it in fiction. This is how ethnic enclaves happen. Someone makes the move and leaves home in search of a better life and once they are settled they tell everyone back home. I didn’t feel like I grew up in New York freaking City with a capital N-Y-C. I grew up in a small community of immigrants, many of whom lived down the block from my family back in Shanghai and now were living down the block from each other in Queens. I wanted to show how these provisional communities are formed, and also how they can be temporary, at least for the people I’m writing about. These families are all trying to escape the cycles of poverty that they find themselves in once landing in New York. They sleep ten to a room, they juggle three or four jobs, and they work themselves nearly to death. Those who succeed and leave that cramped, illegal room with mattresses on the floor, gossip openly and gleefully about the ones who didn’t “make it”. So-called “immigrant” narratives often have this neoliberal focus on the individual. I wanted to go beyond that and show patterns, show the effects of structural racism and poverty on the individuals who live the consequences. I also wanted to show that everyone thinks they are the protagonist of a story, but in fact, we are all marginal characters in someone else’s story and vice versa.

Shelf Unbound: What do you want readers to take away from reading this book?

Zhang: It would be cool if people felt more open after reading the book than before they started. If my stories somehow challenged some steadfast, foundational beliefs. I don’t know—it’s good to shake things up. This is more self-serving, but I also want readers to know that this is a book of literary fiction. I despise the impulse to turn writers who aren’t straight white men into sociologists and cultural critics and journalists. It’s like, no, I’m none of those things. I cannot show you how to pass better immigration policy. I cannot tell you what to think about ALL Chinese in America. But I am doing my best to write fictional stories that are hopefully at least a little compelling and sometimes just to get people to see that when a book has been deemed as the “chronicler”of “X experience” (in my case X= immigrant) is an uphill battle. It would wonderful if after reading my book, the reader’s imagination is broadened, not narrowed. If they could begin to see the absurdity of certain labels like “immigrant fiction” or “ethnic literature” and question the ways we commodify certain identities, expect them to parrot a kind of utility and function that we don’t expect of other identities. All of it is a fancy way of saying I hope the reader can see my book is not some kind of ideological weapon, nor is it more “urgent than ever in this climate.” It’s a book of literature I worked hard on. I want it to bring wonder, curiosity, and pleasure.

Shelf Unbound: What are you working on next?

Zhang: The Chinese part of me is superstitious and tentative about sharing and the American part of me is arrogant and cavalier about divulging! I’m trying to work on a novel and a screenplay. Who knows what will happen.