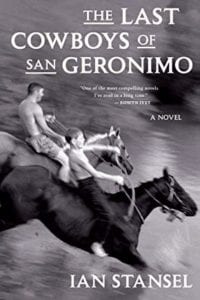

Ian Stansel writes a modern Western classic with his Cain and Abel story.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

houghtonmifflinbooks.com

Shelf Unbound: The Last Cowboys of San Geronimo is a gorgeously written contemporary Western about the lives of two brothers, beginning with one shooting the other and the widow setting off on horseback to follow her brother-in-law and exact revenge. How did you come to the idea of writing a Western?

Ian Stansel: It was a bit accidental, I think. I set out to write about the contemporary equestrian world, which I’d written about a bit before in my first book. I had the idea of feuding brothers—an idea that in one form or another came from my sister, who taught horse riding her whole life. The initial situation of one brother having gunned down the other happened rather quickly, as I remember. But even though I was writing a chase-on-horseback book, it didn’t really occur to me that it was a sort of Western until I was at least a few chapters in. As soon as I had that realization, though, the book took off. So much of the fun of the book was finding moments for the full Western-ness of it to rise to the surface.

Shelf Unbound: You take the reins from Larry McMurtry, Annie Proulx’ Westerns, and Cormac McCarthy and bring the genre forward in a manner that feels both classic and modern. Were you influenced in particular by any earlier authors of Westerns?

Stansel: I love all of the authors you mention. I was also influenced by Charles Portis’s True Grit and Patrick DeWitt’s The Sisters Brothers, as well as Paulette Jiles’s News of the World (which I read after I’d finished the initial composing of the book). As far as the earlier Western writers, I certainly know the work of Louis L’Amour, and obviously he had fun with a chase or two. But when I’m asked this question I feel the need to point out some of the authors who directly influenced the book who have nothing to do with the Western genre. I thought a lot about James Salter’s Light Years and how that book moves between present action and backstory. I also thought about The Great Gatsby, particularly the idea of a person (in the case of my book, two people—the brothers) reinventing themselves. There’s something so wonderfully American about that notion, and I thought it worked well within the Western genre.

Shelf Unbound: The widow Lena and her stable hand Rain, who joins her on the trek, are as integral in this story as the two men. Were you consciously wanting to bring out this female element or did that just happen?

Stansel: Both, really. It just happened, yes, but when I saw those female characters come alive on the page I made a conscious effort to allow them and their relationship to develop. I realized fairly early on in the composition process that I could do something a bit different by having a couple of strong independent women riding across the wilds of California. Of course there are plenty of women in Westerns, but a lot of the time (not all, but a lot) they are dependent on men to help them in their cause. Think of Mattie Ross in True Grit. Of course my book does not take place in the 1880s. It takes place now, and that makes a huge difference. But I did want the two main female characters to be completely capable, never in need of rescuing, at least not by a man. There are a couple other moments in the book when women help each other. This was something I wanted to have happening in the background of the book. In the foreground you have these two brothers dead set on destroying each other, all blustering and violent. Meanwhile, far more quietly, you have women, often strangers, going out of their way to help one another for no other reason than it is the right thing to do in the moment.

Shelf Unbound: On the run, Silas ends up spending the night at a ranch owned by two lesbians and a bi-sexual man, and despite being warmly welcomed by them (until they see a news report and learn his identity) he leaves with a vicious tirade against them. How did this part of the novel come about?

Stansel: I’m actually surprised I haven’t been asked about this more often. It is the moment I struggled with more than any other. This is when we see Silas at his worst. All his worst instincts come rushing out in, as you say, a nasty and completely unwarranted tirade against people who’ve been nothing but welcoming to him. He uses at least one particularly awful homophobic slur, but the whole message of his dialogue there is that they are not as legitimate or American as he is. The thing is, I don’t believe Silas actually thinks these things. Or at least not most of him (obviously it is in him in some ways, or it wouldn’t have come out). What I was trying to show is how a person, when he feels cornered or threatened will lash out at anyone or anything nearby with whatever weapons he can come up with. He is mad about his situation in general, and he is mad at having been caught, and though he knows everything going on is due to choices he has made, in the moment, he attacks and tries to blame this woman and her family.

The other thing this moment does is provide a stepping stone in Silas’s violence. Not too long after this, he is physically violent against another set of relatively innocent people. I felt I needed the verbal/psychological abuse to come first, as going straight to the physical violence would have felt like too much of a jump. But with the two scenes we see a pattern emerging. We see a progression.

I remember emailing my editor about the scene with the homophobic slur and asking if she thought we should cut it. I knew it made sense on a character level, but I also imagined people reading it and feeling like the book was attacking them, that the book was condoning such views and such language. I hope it is clear to readers that this is not the case, or at least it was never meant to condone such thinking. In the end we decided that the scene was important to the character and so we kept it. Even though I know it is true to the character and the story, I do feel uneasy about it. But that’s probably a good thing.

Shelf Unbound: Do you think you will write another Western?

Stansel: My next project won’t be, and maybe not the next. But I could see myself revisiting the genre in the not-too-distant future. I’d need to have the right story, of course, and the right idea for something to do with the genre. I’m a bit restless by nature, and want to do many very different things writing-wise. But I do love horses and I love the West, so it is probably just a matter of time.

Shelf Unbound: You teach Creative Writing at the University of Louisville. What lessons or skills do you most try to impart to your students?

Stansel: It’s easy in a creative writing workshop to get caught up in the technicalities of the craft. And I spend a lot of time on those technicalities. But every once in a while I like to take a moment to remind them of what all that talk is for: to learn to tell good stories.