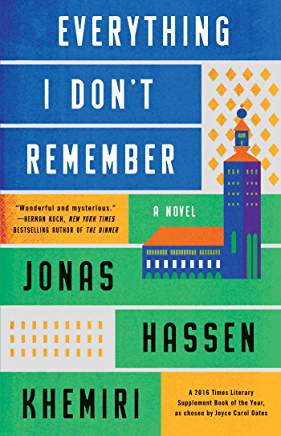

Described as being “reminiscent of the podcast Serial,” Khemiri’s beautiful and deeply meaningful novel is the winner of the August Prize, Sweden’s top literary award.

Atria Books

simonandschusterpublishing.com

Shelf Unbound/Podster: Your novel has been compared to the podcast Serial, in that a novelist seeks to determine whether the main character Samuel’s death was an accident or suicide by piecing together a picture of his life through interviews with his friends, family, and neighbors. Why did you decide to tell this story in this fragmented style?

Jonas Hassen Khemiri: I think one ambition was to try to capture how I actually remember things. My memory has never felt like a trustworthy third person narrator. I always remember things in fragments. Often there are nameless voices that keep disagreeing about what really happened rumbling around in my brains. In this novel I was able to invite these voices to recreate the life of Samuel.

As I was writing the novel I also had a close friend who passed away. I was struck with how all of us who were grieving were really good at defending our version of what had happened. We were constantly remembering the things that could rid us of guilt—the version of the truth that could convince us that we could not have done anything differently. This is reminiscent of what happens in the novel.

Shelf Unbound/Podster: How did you go about creating the character of Samuel?

Jonas: Samuel goes around with a panicky feeling that everything in life is perishable. When writing his life I thought a lot about how much time and energy I have devoted to trying to acquire certain memories and how many words I have written down with the ambition of making life permanent.

In the novel Samuel is being remembered in different ways, and we are never 100 percent sure of who has the final version of who he is. Readers have to piece Samuel together from all the memories that he has left behind. Personally I have always been a big fan of books that force me as a reader to take an active part in assembling the fiction.

Shelf Unbound/Podster: Vandad, Samuel’s close friend and one-time housemate, remains the most enigmatic character as the novel progresses. Why did you want to keep him in the shadows?

Jonas: Vandad is Vandad. He is the only character who follows the reader from the beginning to end. He is the fuel of the novel. He claims not to care about money but is the only character who demands money to share his memories. He claims to be loyal but ends up playing a part in betraying Samuel. I think he needs some shadows in order to be ready to share his story.

Shelf Unbound/Podster: Even in his last moments alive, Samuel is contemplating his emptiness: “… all I see is that blank face, that false body that has never had a genuine emotion, that has never kissed someone without thinking about how the kiss will look to outsiders, that is still waiting for emotion to win out over control someday, and when the red light turns green I put the pedal to the metal …” Did you know at the start that this story would lead to this moment of existential crisis, that he would be thinking these thoughts at the very end?

Jonas: No. I never know where a novel will take me. I only know that if I know where I will end up, the novel tends to die a sad and slow death. No outlines or Excel sheets can revive it. So my working strategy has always been: Listen to the voices. Try (even though it’s hard) not to be scared of letting go of control.

Shelf Unbound/Podster: Immigration policies are a theme in this book. In 2013, your “An Open Letter to Beatrice Ask,” the Swedish Minister of Justice, went viral on social media. In it you poignantly describe your experiences from a young age on of being racially profiled. What message about this topic do you hope readers will take away from this novel?

Jonas: For me shorter political texts demand clarity and anger. Novel writing needs confusion and not being sure about things. In this novel I was not sure about a number of things, for example: How was my home town being transformed when economic forces changed the housing structure? How much I would be ready to pay for feeling safe? Is there a clear-cut boundary between friendship and love? All of these questions play a big part in the novel. But hopefully none of them receive a simple answer.