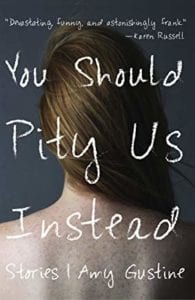

Sarabande Books

Buzzfeedcalled You Should Pity Us Instead one of the “most exciting

new books of 2016.” We totally concur.

Shelf Unbound: These stories are intense and gut-wrenching, frequently looking at failed familial love. What interests you in writing about this subject?

Amy Gustine: Maybe I’m not a romantic by nature. I have never found it particularly interesting to write about burgeoning love between adults, for example. I do however find the subject of spousal connection, keeping that love alive, interesting to explore, and of course my focus the last ten years especially has been on the parent-child relationship. It’s unique. Your child is the one person in the world who you can’t cut from your life, emotionally speaking. You cannot harden your heart to your child, even when the situation may warrant it. The sacrifices a parent will make for a sick child or one who is deeply troubled, for example, are unlike any we would be willing to make for someone else. And yet they still crush us. As much as we love our children, and children love their parents, the relationship is often so very fraught. For children, the approval of a parent is more important, typically, than approval from anyone else. The failure to get it can cripple our sense of self in a unique way. The conflicts from childhood follow us into adulthood like burrs caught in our hearts. All of that just keeps bringing me back, over and over. No story can catch the infinite complexities of life, and so there’s always another angle from which to write about the parent-child relationship.

Shelf Unbound: You create your characters with empathy and nuance, like the neglectful mother Joanne, whose own mother was critical and neglectful. How do you approach writing a character like Joanne?

Gustine: Empathy is in fact the word for it. I had a colicky baby. It wasn’t that hard to imagine what it would have been like if she’d continued to cry like that for a whole year. One of the things that interests me is how much we are capable of forgiving and how in maturity we must face the imperfection of the love that we once felt should, or could, be pure: that of parents for children. This is the thing that’s most interesting about Joanne. She occupies the spot in life from which our vision changes, from child to parent. We are suddenly able to be both at once, and to understand things from this new dual vantage point that we would likely never have understood before. Not all those things we newly understand are pleasant, but some are.

Shelf Unbound: What’s the starting point for you in a story like “All the Sons of Cain,” about an Israeli woman on a risky mission to find her captured son?

Gustine: This story is like a lot of what I write. It started with speculation about an effaced person in the news, in this case Gilad Shalit’s mother. Shalit is a real person who was taken prisoner by Hamas in a border skirmish in Israel, where it meets the Gaza Strip. I was reading an article in The New Yorker about the debate in Israel about whether it was appropriate to exchange Palestinian prisoners to free Shalit, and began to reflect on the mothers of soldiers around the world. One of the concerns in doing a prisoner exchange was that it would encourage Hamas to try to capture more members of the IDF in order to trade them. Hence, the plot of “All the Sons of Cain.”

Shelf Unbound: I was particularly mesmerized by “Half-Life,” in which Sarah is nanny to two kids whose grandfather, a judge, put her in foster care as a child. How did you develop this story and what were you trying to do with it?

Gustine: I had been interested for some time in writing a story about a person who ages out of the foster care system. I was interested in that because children who grow up in foster care must launch themselves into the world in a way that is fundamentally different from most of us, who slowly wade out, always tethered to our parents and other family on shore. The story was an extension of my interest in parenthood in that sense. I’m also fascinated by moral dilemmas, situations in which there is no clear right or wrong, in the fundamentally uncertain nature of the world and thus the uncertain nature of every choice we make. The bigger your choices, the more heavily such uncertainty weighs on you. For a judge who must decide to terminate someone’s parental rights and put a child in foster care, that responsibility is formidable. Thus it was important for the story to make clear that even in hindsight it is not possible to say whether it was better or worse to take Sarah from her home. It is a choice the judge had to make—one or the other, he couldn’t do both or neither—and he must live with that choice and bear its outcome, but he typically doesn’t know its outcome. Here, the outcome stands in front of him, the caretaker of his own grandchildren. Another significant thing I explored in the story is strength and resiliency. While I would never advocate for neglecting a child, there is a sense in which children with neglectful parents can have experiences that build self-reliance and toughness that children with more typically attentive parents do not. That kind of thing, the sort of unorthodox nature of that recognition, interested me and I really enjoyed exploring Sarah’s tough-minded, independent nature and how it informed her caring for Bea.

Shelf Unbound: What appeals to you about writing short stories?

Gustine: I feel out of control when it comes to selecting my own material. Instead, I feel it selects me. There have been times when I so wanted to write a story about a particular person or situation and it has simply not started, like a corroded engine. It looks okay, but all the parts have rusted and it won’t turn over. Other times something sparks and it seems evident to me that the nature of the material either demands a novel-length treatment or a story-length treatment. I do what the material tells me to do. The benefit of a story is that you can get to a finished product so much faster, and the commitment to the character, that person, that way of thinking, is much less. This allows for more experimentation, more risk-taking. When I’m thinking about material for a novel, I get pretty stressed out trying to decide if it’s really worth three, four, maybe seven years of my life, if I can live with the character and the situation that long. If readers will find the material compelling enough for me to justify that time commitment. A collection of stories allows me to cover so much more ground, to keep putting on a new hat and pair of glasses as it were. To look at one thing, like the parent-child relationship, from so many different, even opposing angles, and I like that opposition. A novel is a lot more restrictive, demanding one set of characters and a cohesiveness to the voice and the plot arc.

Shelf Unbound: Will you ever write a novel?

Gustine: I am just finishing edits on one right now in fact. Novels and stories have their own charms and I like them both equally. I enjoy the extended-time commitment and space a novel provides. Every day when I sit down at my desk, I know what I’m working on. I have a framework. The terrifying thing about stories is the same thing that makes them wonderful: you have to keep starting over.