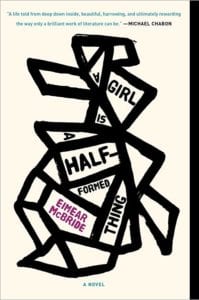

Eimear McBride’s novel is difficult to read but rewards the adventuresome reader with its genius and the heartbreaking story of a troubled young girl with an abusive mother, a disabled brother, and an uncle who molests her. I urge readers to step outside their literary boxes and experience this remarkable book.

Shelf Unbound: You begin the novel with these lines: “For you. You’ll soon. You’ll give her name. In the stitches of her skin she’ll wear your say.” And you keep going like that for the next 226 pages. How did you invent this unconventional style of writing, and what were you trying to achieve with it?

Eimear McBride: The starting point for the style was reading Ulysses. The effect it had on me was so profound that, after the first five pages, I understood everything I had written before had to go in the bin and I had to start again. More conventionally composed prose felt rather bloodless in the light of it and I realised that there are great swathes of existence which cannot be adequately described or explored within those traditional, grammatical frameworks. What I hoped to achieve was an unmediated experience for the reader whereby the writer becomes completely invisible and the reader feels so closely implicated in the protagonist’s experience as to almost be experiencing it within themselves.

Shelf Unbound: Was writing in this style constraining or liberating or both?

McBride: I think it was both. As a writer, to decide to cut all ties with everything you have ever been taught to believe is not only important, but necessary, in order to make your work communicable, is extremely liberating, and terrifying, but mostly liberating. Technically it was very difficult though because I then had to invent my own conventions and work out how to stick to them.

Shelf Unbound: I’ve read that it took you nine years to find a publisher for this book, which last year won the Goldsmith Prize and recently won the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction. What do you think it says about the state of publishing today that publishers were reluctant to take a chance on it?

McBride: Obviously the experience of being unpublished for nine years was hugely dispiriting for me personally and all the more so because I very quickly realised that the problem was far greater than mine. Somewhere along the line—doubtless in pursuit of greater profit margins—publishers decided to stop taking chances on writers, which means they also stopped believing in readers and their desire for work which examines aspects of life that cannot reasonably be explored within the confines of a 350 page whodunnit. It seems to me that many publishers have forgotten that the intrinsic nature of the reader is to be adventurous, interested and open to being engaged by different forms.

Shelf Unbound: One thing I love about this book is that it requires the reader to float along in a state of incomprehension that then develops into partial comprehension and then into complete comprehension, if not of every moment but of the story as a whole. Were you concerned at any point that readers would struggle with it?

McBride: I was always aware that I was making a big ask of readers. I knew, chances were, when they opened the first page and saw all those short, oddly punctuated sentences, it might alarm them a little. But, communicating the story was always central to my plan so I knew that, if I did my job properly, readers who were willing to go through that period of adjustment to the style would hopefully find a compelling story there to make their initial extra effort seem worthwhile.

Shelf Unbound: A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing is your debut novel. Will your next one be in a similar style or perhaps more traditional? Or do you plan a whole other form of invention?

McBride: I’m still interested in language and what it can be cajoled into doing, so I won’t be returning to the traditional any time soon. That said, I built the language of A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing around that particular story and next time I’ll do the same, which means it will be different again.