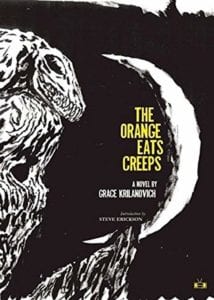

Shelf Unbound: The OrangeEats Creeps is a relentless existentialist nightmare told from the point of view of a nameless female hobo

vampire junkie. I’ll pull out the key word here: existentialist. Is that the main thing you were going for?

Grace Krilanovich: Yes, well, a lot’s at stake here and the dread, the leakage, the thrills and the devouring are all of the psyche as well as the body. I was going for something ultra-dramatic and ridiculous and at the same time quiet and sleepy, like a prolonged, hissing draft of air escaping from an inner tube. I felt it was worthwhile to risk cliché, excessiveness, and sentimentality if it meant approaching some kind of “existential” truth. What I certainly didn’t want to do was limit it too early, define what it was, wrap it up neatly, tell it what it should be. That seemed antithetical to the book’s purpose, its tone, and the form itself. Much of it is rooted in the sensory, the lived experience of the body—just heightened by multiple threats from external forces: drugs, predators, the landscape. And from internal forces: the throbbing bruise pressure of soul sickness.

Shelf: “Twilight this isn’t,” writes Steve Erickson in the book’s introduction, and indeed, there is not an ounce of vampire cliché in this literate novel. Why make the characters actual vampires, though,

rather than just predatory human degenerates?

Krilanovich: I wanted the confusion there, or rather, not knowing one way or another. Are they? Aren’t they? In terms of “actual vamps” vs. merely “predatory human degenerates”—there are lots of great examples of the latter: Evil Companions, de Sade, Story of the Eye, Buffalo Bill, the Mentors—but it’s the parasitism of actual vampires that had the richness of meaning that I was after. All of the shared cultural anxiety over our perceived interior purity, our bodies’ supposed tidiness and impermeability, wouldn’t have much traction without the imminent threats to Our Precious Fluids by the parasitic force of the vampire. Everyone fears being sucked dry by some leisurely, non-productive ne’er do well. Imagine the insidiousness of all that languid reclining on overstuffed furniture, keeping of non-farmer’s hours (talk about going against the grain), being out of step with the world, willingly or unwillingly. Not being a producer, instead, a pure consumer. And what are they consuming? Life itself. The life essence of living, productive, “daytime” people. Converting them/destroying them.

I don’t see my characters as literal vampires to the extent that Kiefer Sutherland and Jason Patric were in The Lost Boys, like Bill Paxton and Jenette Goldstein were in Near Dark—though I learned a lot about tone and the sick feeling I wanted to capture for my own near-vamps. Those movies have mystique and a creepy pull that Interview with the Vampire and Twilight don’t, although I still enjoy those two as films. I love going to see the new Twilight movie. I laugh and laugh while my boyfriend shields his eyes and pretends to go to sleep, even though he’s laughing on the inside, I’m sure. Let me make it clear that vamp clichés are still great. It’s a very important cliché to think about and make art about, and it will always be.

Shelf: The main character is witness to, victim of, and participant in

all manner of depravity. I ultimately had sympathy for her, though,

and was moved by her poignant quest for her soul mate/lover/sister Kim. How do you, as the writer, feel about the main character?

Krilanovich: Very tenderly. You know, I worked on this book for so long, six years. Inevitably (if things are going well) your characters take on a life of their own and begin dictating what will happen to them in the story. Or they just start going about their business and you’ve got to take it all down fast. It’s your job to listen, and be truthful, and do right by them. And of course you get attached. A great thing was being able to slip back into that voice for the revisions that happened after the book was accepted for publication. It was so much easier and surprised me because I thought that after two and a half years (and after having started a new novel) the characters would be faded out old wooden clothespin dolls of their true selves. But that wasn’t the case at all. Some of my favorite stuff was written last.

Shelf: You connect the main character with Donner Party survivor Patty Reed and her wooden doll. What is the meaning of this connection?

Krilanovich: It’s partly a personal fascination with the Donner Party and their plight. Growing up in California you’d take a fifth grade field trip to Sacramento and Sutter’s Fort where there’s a Donner Party exhibit and they’ve got the doll on view. Patty Reed’s Doll is a ‘50s illustrated chapter book that we read in class, strange as it may seem to have a cute kids’ version of the Donner Party tragedy. It’s something John Waters should adapt ASAP. So there’s that. But I also felt Patty Reed’s doll (the book and the phenomenon) had certain connections to the story I was writing. Thematically, there are echoes throughout Orange: parasitic beings (once again) with their own agendas, maybe a comforting little pet/confidant here or there and those little yapping sub-entities House Mom makes do her bidding. A lot of stuff in the novel about hibernation, foraging, madness setting in in the middle of nowhere, the site of unknown tragedy, the macabre, bones and artifacts buried in the earth, all those things I hoped would be deepened and broadened by the Donner connection.

Shelf: How do you describe your writing style?

Krilanovich: Ideally: lush, maniacal, fearless. Realistically: Up to 11, relentless, no brakes; a set constellation of words that crop up again and again. How many times can I get away with using the words “gelatinous,” “ashen,” “creepy,” “hippie,” and “vague” in one work of fiction?

Shelf: What are you working on now, and are you writing it in a similar style to The Orange Eats Creeps?

Krilanovich: Another novel. I would definitely say it’s written in a style similar to The Orange Eats Creeps. But this is a historical romance, Coast Range of California, circa 1870. Nights seem to stretch on into eternity. A pack of brindle mutts runs around under cover of darkness, leaving a trail of gore in its wake.