By Sarah Kloth

In this interview, we sit down with translators Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae to explore the complexities of bringing Mater 2-10, Hwang Sok-yong’s epic, multi-generational novel, to an English-speaking audience. They share their experiences navigating the rich historical and cultural layers of the text, offering insight into the challenges and rewards of translating this powerful story that spans a century of Korean history. Through their collaboration, they have brought to life the struggles and resilience of ordinary Koreans across generations, ensuring that Hwang’s masterful work reaches a wider audience.

Mater 2-10 is a complex and multifaceted novel that spans over a century of Korean history. How did you approach the challenge of translating such a dense and historical text?

YJ: I think co-translation was key to tackling such a dense novel. Translating half the book was still overwhelming but knowing that you’re not facing the challenge alone was reassuring for me. Like most translations, historical text requires considerable research and Mater 2-10 was no different, especially since real-life figures, events, and places have been woven into the story. Moreover, the novel describes certain places and areas in Seoul that still exist but some of the landscape has changed over the course of a century, so we also had to examine old maps and even visit certain neighborhoods in person to better grasp descriptions about them in the story.

SKR: I heartily second everything that Youngjae said. I think Mater 2-10 is an example of a book that lends itself to being co-translated. Typically, most books do well, if not better, with a single translator to control the voice and style. But given the complexity and the multitude of voices in Mater 2-10, I believe the translation was improved by having more than one person on it.

2The novel’s protagonist, a laid-off railroad worker, stages a dramatic protest atop a factory chimney, while his ancestors visit him to recount their own struggles. How did you navigate the interplay between the protagonist’s present-day experience and the historical flashbacks in your translation?

SKR: What I noted about the way Hwang handled the interplay is that the transitions felt very smooth and matter-of-fact, such as in the opening scene when Jino steps off of the chimney and onto a cloud which then turns into solid ground. Likewise, when Jino is visited by ghosts, he’s never surprised or alarmed but takes it in stride as if it’s the most ordinary thing. I wanted to create a similar, matter-of-fact effect in English. This meant avoiding words like “suddenly” or making the transitions seem too dramatic or “magical.” Hwang Sok-yong himself dislikes having his work referred to as speculative or as magic realism; instead, he calls his style “folk realism.” I suppose ghosts are only “speculative” if you’ve never felt the presence of a loved one who passed away, or have never felt haunted by the past. (And it might be worth pointing out here that the ghosts who visit the protagonist aren’t “ancestors” in the usual sense of distant or past generations—they’re all people he knew in his lifetime.) Aside from that, what I also noticed was that the prose in the modern sections tended to be crisper and more concise, whereas the flashback scenes had longer sentences with flowy descriptions of daily life back then. Those scenes struck me as very nostalgic, especially since many of the details were of bygone things, so I made a point of leaning into those moments by not editing out too many details and just letting the prose be denser and rich with detail than in other parts.

Hwang Sok-yong’s writing often includes rich, culturally specific details and historical references. What strategies did you employ to ensure these elements were accurately and effectively conveyed to English-speaking readers?

YJ: For Mater 2-10, such elements turned out to be terms of address, food names, place names, and interjections. For terms of address, we first tried to translate them completely, then tried transliterating them all, then decided to keep only the family titles that recurred frequently in dialogue to minimize confusion. This strategy was adopted in slight variations for different elements and we explained our reasons as best we could in the translators’ note at the beginning of the book to warn(?) readers beforehand of the challenges lying ahead. So, if you haven’t read the book yet, I’d recommend starting with the translators’ note instead of jumping straight into the story.

The novel features both male and female narratives, including mythical and magical elements. How did you balance the different narrative voices and maintain the integrity of the original text’s tone and style in your translation?

YJ: I guess the answer ultimately lies in the original text. The main male and female characters are well established through various episodes involving them, which leaves less room for confusion as to what their narrative tone should each sound like. Also, I think the information-heavy passages that occasionally come up help maintain a certain balance in terms of style and provide more in-depth historical context that mythical and magical elements cannot offer.

The translation process can reveal new dimensions of a text. Were there any particular passages or themes in Mater 2-10 that you found especially challenging or rewarding to translate?

SKR: In general the prose in the older scenes was challenging because of the amount of grammatical juggling we had to do and because we were constantly weighing how to handle cultural references that didn’t have direct equivalents in English. But it was also rewarding in that it was an opportunity to think more deeply about how things like sentence length or density of detail shape the meaning of a text. Aside from that, the part I found most personally challenging to translate was Jangsan’s story. I’ll leave out the details so as to avoid any spoilers, but it was hard to get through that part without crying.

YJ: The passage where Jino reminisces about the old songs he learned from his grandmother or the song that the coal hauler sang were especially challenging and rewarding to translate. Lyrics can be tricky to translate in itself because you have to consider rhythm and rhyme, but some of the songs in the story leaned more toward folk songs from a different time, and one of them even included vocables, so we had to play with words quite a bit before we could come up with something that seemed to make sense.

Hwang Sok-yong’s novel has been praised for its depiction of worker exploitation and national history. How did you ensure that the translation remained faithful to these social and political critiques?

SKR: Mostly we just followed Hwang Sok-yong’s cues and made sure not to leave anything out without a very, very good reason to do so. We also made the decision to keep things like the socialist slang (e.g. orgs, reppo, etc.) as it sounds in Korean rather than look for equivalent translations, because we didn’t want to risk omitting or changing any nuances. Also, for the parts where Hwang lists statistics (e.g. the numbers of those who died in massacres), we made sure to keep those details as they appeared in the Korean. The numbers found in English-language sources tend to be smaller, which raised questions during the fact-checking phase of the editing process about the reliability of different sources, but we advocated for prioritizing Korean-language sources. In that sense, this book is more than just a fictional narrative, it’s also an archive of historical information that is not easily found outside of Korea.

Can you share an example of a specific challenge you faced in translating Mater 2-10 and how you resolved it?

YJ: For me, the passage describing the driver’s compartment of a locomotive was challenging because I knew nothing about locomotives. I had to rummage through multiple sources explaining how locomotive engines work and sift through many images with labels of all the different parts of a driver’s compartment. Unfortunately, no amount of searching was able to help us come up with a translation for the architectural term “maru,” so we had to transliterate it, add a description of it in the text, and explain through the translators’ note about why it was particularly challenging to translate.

What was the collaborative process like between you, Sora Kim-Russell, and Youngjae Josephine Bae? How did you work together to ensure a cohesive translation?

YJ: We split the book in half and did nine chapters each. Then we swapped manuscripts to review and exchange edits and had plenty of discussions about all the nitty-gritty details. I used to be a student of Sora’s and we had known each other for a few years before this project came along, so I suppose open, frequent communication based on trust was key to ensuring a cohesive translation. Also, I think going through multiple revisions with our editor at Scribe added an extra layer of cohesion to our translation.

What do you hope English-speaking readers take away from Mater 2-10? How do you see the translation contributing to the book’s impact in the global literary landscape?

YJ: As a reader, I enjoyed the episodes featuring female characters like the unusually strong Juan-daek who keeps rescuing her family in life and after life, or Shin Geumi, who is a New Woman but also clairvoyant, so I hope English-speaking readers find such episodes entertaining as well. As Hwang Sok-yong mentioned in the book’s afterword, he wrote Mater 2-10 to help fill a void in Korean literature where stories depicting the lives of ordinary industrial workers are hard to come by. I think the book’s translation can contribute to the global literary landscape in a similar way because Korean historical fiction featuring laborers and folk realism is already a rarity.

SKR: Regarding the book’s impact, there is a growing body of literature in English that addresses different aspects of how modern South Korea came to be. For example, Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, Juhea Kim’s Beasts of a Little Land, and Yu Miri’s The End of August are all epic novels set during the same time period as Mater 2-10, but they each approach that period from a different angle and with different casts of characters. Mater 2-10 is very much in conversation with those novels and adds new elements, such as the role of industrial workers, the political turmoil that characterized colonial and post-colonial Korea, and highly detailed depictions of daily life at that time.

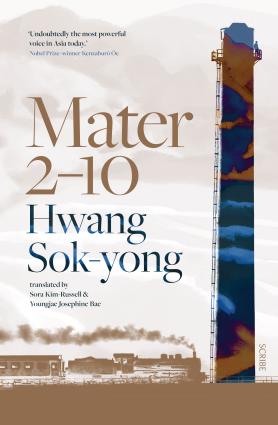

Mater 2-10

Hwang Sok-yong, Sora Kim-Russell (Translation), Youngjae Josephine Bae (Translation)

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2024 INTERNATIONAL BOOKER PRIZE

“Undoubtedly the most powerful voice in Asia today.”

– Nobel Prize–winner Kenzaburo Oe

In contemporary Seoul, a laid-off worker stages a months-long sit-in atop a sixteen-story factory chimney. During the long and lonely nights, he talks to his ancestors, chewing on the meaning of life, on wisdom passed down the generations.

Through the lives of those ancestors, three generations of railroad workers, Mater 2-10 vividly portrays the struggles of ordinary Koreans, starting from the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation, and right up to the twenty-first century. It is at once a gripping account of a nation’s longing to be free from oppression, a lyrical folktale that reflects the blood, sweat, and tears shed by modern industrial laborers, and a culmination of Hwang’s career—a masterpiece thirty years in the making.

A true voice of a generation, Hwang shows again why he is unmatched when it comes to depicting the roots and reality of a divided nation and bringing to life the trials and tribulations of the Korean people.