By Michele Mathews

Have you ever considered diving into a book that’s been translated from another language, or perhaps you’ve already ventured into this literary realm? Each year, only a select number of books are translated, but the diversity of languages being made available in English continues to expand. For example, the curated list you’ll find here represents an impressive sixteen different languages from around the globe, showcasing the rich tapestry of global storytelling.

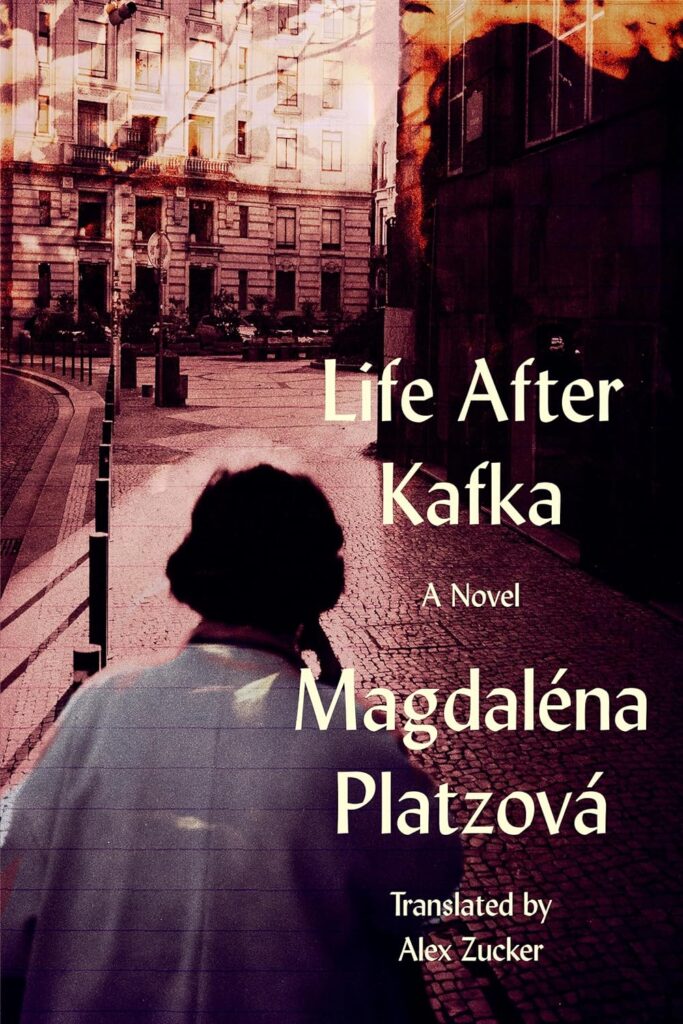

Czech

1. Life After Kafka

By Magdaléna Platzová

Translated by Alex Zucker

Franz Kafka scholars know Felice Bauer, his one-time fiancée, through his Letters to Felice, as little more than a woman with a raucous laugh and a taste for bourgeois comforts. Life After Kafka is her story. The novel begins in 1935 as Felice flees with her children from Hitler’s Berlin, following her family and members of Kafka’s entourage—including Grete Bloch, Max Brod, and Salman Schocken—as they try to escape the horrors of the Holocaust. Years later, a man claiming to be Kafka’s son approaches Felice’s son in Manhattan and the drama surrounding Kafka’s letters to Felice begins.

While taking the measure of literary fame’s long shadow, Life After Kafka depicts the magic and poison of memories, and what we cling to when all else is lost. Most of all, it illuminates the bravery required to move forward through the shattered remains of one world to rebuild life in a new one.

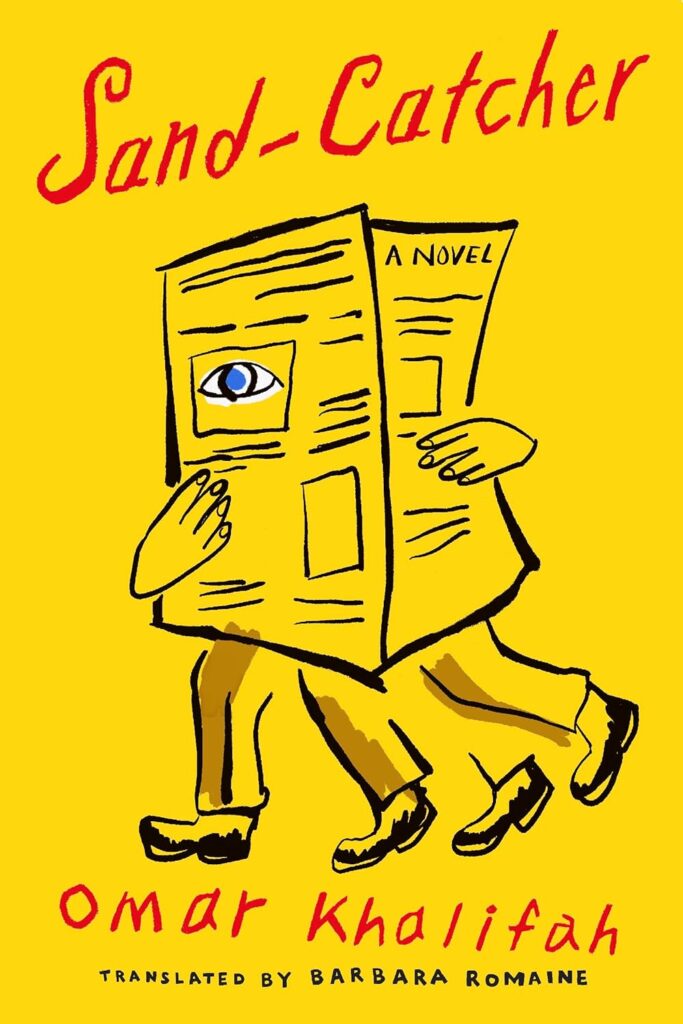

Arabic

2. Sand Catcher

By Omar Khalifah

Translated by Barbara Romaine

Four Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are tasked with writing a profile on one of the last living witnesses of the Nakba, the violent expulsion of native Palestinians by the nascent state of Israel in 1948. Confident that the old man will be more than willing to go on record about his experiences, the reporters are nonplussed when they are repeatedly, and obscenely, rebuffed by the man and his grandchildren. This living witness to history seems to have no desire to be interviewed, no desire for his memories to be preserved, no desire to talk. As the team’s editor-in-chief puts more and more pressure on the young journalists, a battle of wills escalates to ruinous consequences that will leave no one unscathed.

Omar Khalifah’s debut novel Sand-Catcher is at once a polyphonic satire and a tightly plotted tale of suspense. Walking the line between gallows humor, rage, and depthless heartbreak, it is a unique reflection of contemporary Palestinian identity in all its facets.

3. Children of the Ghetto

By Elias Khoury

Translated by Humphrey Davies

Adam Dannoun’s story is one of beginnings. Born in a war-torn Israel, within the confines of the Lydda ghetto, Adam dreams of becoming a writer. He is just an infant when Jewish forces uproot and massacre thousands of Palestinians in the 1948 Nakba, including his own father. Adam’s mother, crumbling with loss, takes her son to Haifa and remarries. Soon she feels stifled by her new husband. Adam flees this lifeless home and writes himself a second beginning. With nothing but his father’s will and the image of his mother at the doorway, Adam is born again into the streets of Haifa. It is there he meets an auto-shop owner, Gabriel, who helps him spin a new life. Adam Dannoun shapeshifts into Adam Danon, an Israeli born into the Warsaw ghetto, and Gabriel’s younger brother. There are limits to this charade, tenuous lines he’s forbidden to cross—and when he falls in love with Gabriel’s only daughter he steps, unawares, into a third life. We follow Adam through his studies in Haifa and into his New York exile, bearing witness as he confronts the horrors of the past that continually assert themselves in the present. Following My Name Is Adam, Star of the Sea is the second installment of a brilliant trilogy—an epic tale of love, survival, and ongoing devastation. Khoury weaves personal and cultural memory into a tale that humanizes the complex Palestinian experience, and traces the careful contours of the unspeakable.

4. The Book Censor’s Library

By Bothayna Al-Essa

Translated by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain

The new book censor hasn’t slept soundly in weeks. By day, he combs through manuscripts at a government office, looking for anything that would make a book unfit to publish—allusions to queerness, unapproved religions, any mention of life before the Revolution. By night, pilfered novels pile up in the house he shares with his wife and daughter, and the characters of literary classics crowd his dreams. As the siren song of forbidden reading continues to beckon, he descends into a netherworld of resistance fighters, undercover booksellers, and outlaw librarians trying to save their history and culture.

Reckoning with the global threat to free speech and the bleak future it all but guarantees, Bothayna Al-Essa marries the steely dystopia of Orwell’s 1984 with the madcap absurdity of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, resulting in a dreadful twist worthy of Kafka. The Book Censor’s Library is a warning call and a love letter to stories and the delicious act of losing oneself in them.

French

5. Sister Deborah

By Scholastique Mukasonga

Translated by Mark Polizzotti

When time-worn ancestral remedies fail to heal young Ikirezi’s maladies, she is rushed to the Rwandan hillsides. From her termite perch under the coral tree, health blooms under Sister Deborah’s hands. Women bare their breasts to the rising sun as men under thatched roofs stand, “stunned and impotent before this female fury.” Now grown, Ikirezi unearths the truth of Sister Deborah’s passage from America to 1930s Rwanda, and the mystery surrounding her sudden departure. In colonial records, Sister Deborah is a “pathogen,” an “incident.” Who is the keeper of truth, Ikirezi impels us to ask, Who stands at the threshold of memory? Did we dance? Did she heal? Did we look to the sky with wonder? Ikirezi writes on, pulling Sister Deborah out from the archive, inscribing her with breath. A beautiful novel that works in the slippages of history, Sister Deborah at its core is a story of what happens when women—black women and girls—seek the truth by any means.

6. Canoes

By Maylis de Kerangal

Translated by Jessica Moore

“When did I start placing myself in the fable?” A young Parisian wonders as she tells her son the legend of Buffalo Bill, a spectral presence atop the mountain in their small Colorado town. She has just moved to the United States and everything disorients her – suburbs stretching along reptilian highways, a new house rigged like a studio set, but most of all, the sound of her husband’s voice. Sam speaks with a different tone in English, not the soft and swift timbre of his native French. From a voice made new, Maylis de Kerangal opens up a torrent of curiosities, hauntings, and questions about place and language.

Seven stories ricochet off of this exhilarating central novella, and in them we hear female voices by turns indelibly witty, insightful, intimate, bracing, and profoundly interconnected. The women of these stories are mad about: stones, molds of human jaws, voicemail recordings, sonic waves, UFOs, and always how the texture of human voice entwines with their obsessions. With cosmic harmonics, vivid imagery, and a revelatory composition, Canoes will leave its reader forever altered.

7. Great Fear on the Mountain

By Charles Ferdinand Ramuz

Translated by Bill Johnston

Feed is running low in a rural village in Switzerland. The town council meets to decide whether or not to ascend a chimerical mountain in order to access the open pastures that have enough grass to “feed seventy animals all summer long.” The elders of the town protest, warning of the dangers and the dreadful lore that enfolds the mountain passageways like thick fog. They’ve seen it all before, reckoning with the loss of animals and men who have tried to reach the pastures nearly twenty years ago. The younger men don’t listen, making plans to set off on their journey despite the elders’ pleas. Strange things happen. Spirits wrestle with the headstrong young men. As tension builds, Ramuz captures the terror seeping through each man’s spirit. Rhapsodic and tense, Ramuz brings the Swiss mountainside to life. One of the most talented translators working today, Bill Johnston captures the sublime turns of the original in his breathtaking translation.

8. Vladivostok Circus

By Elisa Shua Dusapin

Translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins

Tonight is the opening night. There are birds perched everywhere, on the power lines, the guy ropes, the strings of light that festoon the tent . . . when I think of all those little bodies suspended between earth and sky, it makes me smile to remind myself that for some of them, their first flight begins with a fall.

Nathalie arrives at the circus in Vladivostok, Russia, fresh out of fashion school in Geneva. She is there to design the costumes for a trio of artists who are due to perform one of the most dangerous acts of all: the Russian Bar.

As winter approaches, the season at Vladivostok is winding down, leaving the windy port city empty as the performers rush off to catch trains, boats and buses home; all except the Russian bar trio and their manager. They are scheduled to perform at a festival in Ulan Ude, just before Christmas.

What ensues is an intimate and beguiling account of four people learning to work with and trust one another. This is a book about the delicate balance that must be achieved when flirting with death in such spectacular fashion, set against the backdrop of a cloudy ocean and immersing the reader into Dusapin’s trademark dreamlike prose.

9. About Uncle

By Rebecca Gisler

Translated by Jordan Stump

At an age when she’d rather be making her own way in the world, an unnamed young woman finds herself moving to a small town at the seaside to care for her uncle. He’s a disabled war veteran with questionable habits, prone to drinking, gorging, and hoarding—not to mention the occasional excursion down into the plumbing, where he might disappear for days at a time. When the world starts to shut down, Uncle and his niece become closer than ever. She knows his every move—every bathroom break he takes, every pill he swallows—and finds herself relying more and more on this strange man, her only company in a shrinking world. But then Uncle’s health takes a turn for the worse: He’s sent to a hospital that cares for cats, dogs, and Uncles, and any way for her to make sense of this eerie new reality, and her place within it, falls apart.

Poet-novelist Rebecca Gisler’s debut novel, set against our increasingly disjointed world, welcomes readers into a home of shut-ins as cozy as it is claustrophobic. Gisler’s bright, winding prose, masterfully translated from French by Jordan Stump, offers a rare witness to the complex ways in which we order our lives, for better or worse, inside and out.

Spanish

10. A Question of Belonging

By Hebe Uhart

Translated by Anna Vilner

“It was a year of great discovery for me, learning about these people and their homes,” Hebe Uhart writes in the opening story of A Question of Belonging, a collection of texts that traverse Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, and beyond. Discoveries sprout and flower throughout Uhart’s oeuvre, but nowhere more so than in her crónicas, Uhart’s preferred method of storytelling by the end of her life.

For Uhart, the crónica meant going outside, meeting others. It also allowed the mingling of precise, factual reportage and the slanted, symbolic narrative power of literature. Here, Uhart opens the door on all kinds of people. We meet an eccentric priest who conducts experiments down by the riverside hoping to land on a cure for cancer; a queenly (read: beautiful and relentlessly indolent) teenage girl; a cacique of the Pueblo Nación Charrúa clan, who tells her of indigenous customs and histories. She writes with characteristic slyness. Vitamins are “brown and circular, like grainy meatballs,” a racist blonde woman “must have been a fourth-tier secretary in her home country, but in La Paz she bossed people around with the vigor of a resurrected louse.”

From lapwings, road-side pedicures, and the overheard conversations of nurses and their patients, to Goethe and the work of the Bolivian director Jorge Sanjinés, Uhart reinvigorates our desire to connect with other people, to love the world, to laugh in the face of bad intentions, and to look again, more closely. In the last lines of the title story, Uhart writes, “And I left, whistling softly.” Wherever she may have gone, we are left with the wish we could follow alongside.

11. The Brush

By Eliana Hernández-Pachón

Translated by Robin Myers

Pablo Rodríguez steps thirteen paces out into the night and buries a wooden box. Its contents: a chain, a medallion, a few overexposed photographs, and finally, a deed. He burrows into the ground without knowing quite why, but with the certainty of a heavy change pressing through the air, of fear settling “like a cat in his throat.” Meanwhile, his wife Ester a sharpshooter and keeper of all village secrets slips into her fifth dream of the night. As Ester tosses and Pablo pats his fresh mound of earth, another character emerges in Eliana Hernández Pachón’s vivid and prophetic triptych.

The Brush is a tangled grove, a thicket of vines, an orchid pummeled with rain. Told from the voices Pablo, Ester, and the Brush itself, Hernández Pachón’s poem is an astounding response to a traumatic event in recent Colombian history: the massacre in the village of El Salado between February 16 and 21, 2000. Paramilitary forces tortured and killed sixty people, interspersing their devastating violence with music in the town square. The Brush is an incantatory, fearless exploration of collective trauma and its horrific relevance in today’s Colombia, where mass killings continue. It is also an extraordinary depiction of ecological resistance, of the natural world that both endures human cruelty and lives on in spite of it.

12. What Comes Back

By Javier Peñalosa M.

Translated by Robin Myers

Javier Peñalosa M.’s What Comes Back is a procession, a journey, a search for a body of water that has disappeared. Featured in separate sections, original Spanish poems and Robin Myers’s English translations highlight tender ruminations on loss, memory, and communion. Just as landscapes witness and “preserve what happens along the length of them,” so do people. We watch as travelers navigate realms between the living and the dead, past mountains and dried-up rivers to map, trace, and remember the past and future. Several sections, each bearing the title “What Comes Back,” guide readers on a looping voyage where they are “orbited around the gravity of what had come to be”: the absence of Mexico City’s rivers and other absences wrought by war, climate change, and forced migration. What remains is a desire to name the missing, to wrest belonging from dispossession, endurance from erasure. Rattled between ecological destruction and human violence, the spirit pushes on toward connection and community.

13. The Murmuration

By Carlos Labbé

Translated by Will Vanderhyden

On the eve of the 1962 World Cup in Chile, a retired sports commentator with a secret ability to influence living beings with his voice encounters one of the directors of the Chilean national team—a feminist with a covert agenda—on an overnight train ride to Santiago. The director convinces the commentator to return to broadcasting in order to call Chile’s matches and to utilize his unique vocal power to influence their outcomes.

Later, when Chile is facing off against Brazil in the semifinal match, the plan diverges from one of conventional victory and the narrative bifurcates, simultaneously tracking the action on the field and a startling sequence of events that is unfolding in one of the stadium’s luxury boxes, and what initially looks like a story of intrigue and action and an exploration of class warfare, representation, and social justice, emerges as a novel that enacts the notion that art can only transcend through collective creative action.

Within the world of Carlos Labbé’s fiction, this novel can be understood as a continuation and broadening of the political project signaled in his early work and a doubling-down on the formal playfulness and elusive sensibility that characterizes all of his fiction. Popular forms and genres (from science fiction and journalism in Navidad & Matanza, to detective fiction in Loquela, to pop music and protest movements in Spiritual Choreographies) have always been integral to Labbé’s oeuvre, and with The Murmuration he engages the world of professional soccer, making his most direct appeal to the masses yet.

14. Sensitive Anatomy

By Andrés Neuman

Translated by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia

In the era of compulsive touch-ups and digital poses, perhaps it is time to re-read our body in order to rescue. Perhaps it is time to re-read our body in order to rescue it and embrace it with joy.

The thirty brief chapters of Sensitive Anatomy form a celebration of the body in its glorious entirety, from the most obvious zones to those commonly less appreciated. This is a poetic, political, and hedonistic journey across the very matter that makes us. A book that questions how we see ourselves, how we are made to see, and what beauty really is. It playfully stands against the culture of Photoshop, against oppressive images, against all those edits and erasures which end up excluding the vast majority of real people.

Uniting genres, genders, and generations through a collective voice, Neuman continues to extend the limits of short-form prose with irony and creative freedom. All bodies are welcome here.

15. Once Upon Argentina

By Andrés Neuman

Translated by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia

One day, a young man receives an unexpected letter from his grandmother, kicking off a literary adventure that brings home to him everything he has not seen.

Once Upon Argentina relates the lives of the narrator’s relatives— a group of people from all over the world gathered in a land where immigrant traditions merge and thrive. The lives of these relatives intersect, like a set of Matryoshka dolls or a hall of mirrors, as the personal and social stories of twentieth century Argentina converge.

Beyond these tales of hardship and triumph, Andrés Neuman’s novel experiments with the nature of the autobiography, encom- passing prenatal memories, expanding the autofiction genre with a new voice and twist. Merging present and past, collective experiences and his own, the narrator explores a genealogy populated by unforgettable characters, offering us the story of the construction of a country, his Argentine childhood, and his early literary discoveries.

With extraordinary delicacy and intensity, combining elegy, tragedy, and humor, Andrés Neuman reveals a world as real as it is fantastic, as strange as it is our own. Once Upon Argentina is a coming-of-age tale, a political novel, and a love letter to the absent ones.

Danish

16. What Kingdom

By Fine Gråbøl

Translated by Martin Aitken

Fine Gråbøl’s narrator dreams of furniture flickering to life. A chair that greets you, shiny tiles that follow a peculiar grammar, or a bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron. Fine’s narrator is obsessed with the way items rise up out of their thingness, assuming personalities and private motives. She lives in a temporary psychiatric care unit for young people in Copenhagen, practicing daily routines that take on the urgency of survival (peeling a carrot, drinking prune juice, listening through thin walls). Gråbøl’s prose demands that you slow down, follow just a footstep behind as she charts a wisdom of her own.

Kashmiri

17. For Now, It Is Night

By Hari Krishna Kaul

Translated by Gowhar Fazili, Gowhar Yaquoob, Kalpana Raina, and Tanveer Ajsi

Hari Krishna Kaul’s short stories, shaped by the social crisis and political instability in Kashmir, explore – with a sharp eye for detail, biting wit, and empathy – themes of isolation, alienation, corruption, and the social mores of a community that experienced a loss of homeland, culture, and language. His characters navigate their ever-changing environs with humor as they make uncomfortable compromises to survive. Two friends cling to their multiplication tables while the world shifts around them; a group of travelers are forced to seek shelter in a rickety hostel after a landslide; a woman faces the first days in an uneasy exile at her daughter-in-law’s Delhi home. Kaul dissects the ways we struggle to make sense of new surroundings. These glimpses of life are bittersweet and profound; Kaul’s characters carry their loneliness with wisdom and grace. Beautifully translated in a unique collaborative project, For Now, It Is Night brings many of Kaul’s resonant stories to English readers for the first time.

Korean

18. Wafers

By Ha Seong-nan

Translated by Janet Hong

When truth is more gruesome than fiction—Ha Seong-nan is there. When people give in to their most intrusive thoughts—Ha Seong-nan is there. When man is more animal than animals themselves—Ha Seong-nan is there.

In Wafers, her third short-story collection to appear in English, Ha continues to weave troublesome coincidences into the seemingly banal in her signature style of engrossing and unsettling prose. A best-seller in Korea, Ha Seong-nan is one of the stars of contemporary short fiction, writing edgy, socially conscious stories that bring to mind the novels of Han Kang and the film Parasite.

19. Rina

By Kang Young-sook

Translated by Kim Boram and Janet Hong

Rina is a defector from a country that might be North Korea, traversing an “empty and futile” landscape. Along the way, she is forced to work at a chemical plant, murders a few people, becomes a prostitute, runs a lucrative bar, and finds a solace in a motley family of wanderers all as disenfranchised as she. Brutal and unflinching, with elements of the mythic and grotesque interspersed with hard-edged realism, Rina is a pioneering work of Korean postmodernism.

20. Years and Years

By Hwang Jungeun

Translated by Janet Hong

Years and Years opens with the elderly Yi Sunil, devoted housewife and mother of three, making her annual pilgrimage to a remote village in South Korea to visit her grandfather’s grave—likely for the final time. What follows is a multigenerational exploration of desires thwarted by societal obligations and mores for the women in this family.

Sejin, the middle child, keeps her sexuality closeted, while her older sister, Yeongjin, finds herself financially responsible for the rest of the family, forcing her to give up on her personal dreams. Meanwhile, the youngest, Mansu, leaves the family for New Zealand, where he is free to pursue his own career and life, ironically supported by the sacrifices of his mother and sisters.

Tracing the lives of the family’s three women, Years and Years exposes the ways in which, despite the empathy we harbor for our loved ones, we inevitably trap one another in particular roles, while also illuminating our resolve to carry on through the constraints of time and tradition.

21. Counsel Culture

By kim hye-jin

Translated by Jamie Chang

Haesoo is a successful therapist and regular guest on a popular TV program. But when she makes a scripted negative comment about a public figure who later commits suicide, she finds herself ostracized by friends, fired from her job, and her marriage begins to unravel. These details come to the reader gradually, in meditative prose, through bits and pieces of letters that Haesoo writes and finally abandons as she walks alone through her city.

One day she has an unexpected encounter with Sei, a 10-year-old girl attempting to feed an orange cat. Stray cats seem to be everywhere; they have the concern of one other neighborhood woman and the ire of everyone else. Like Haesoo and Sei, the cats endure various insults and recover slowly. Haesoo, who would not otherwise care about animals or form relationships with children, now finds herself pulled back by degrees into the larger world.

Urdu

22. Kettle Drum

By Siddique Alam

Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi

The Kettledrum and Other Stories introduction the extraordinary voice of renowned Urdu novelist, short story writer, playwright, and critic Siddique Alam. He is considered to be a modern master, whose introduction of fantastical elements into his narratives and experimental techniques (especially in his plays) have garnered him critical acclaim and popular success.

With each story in the collection he creates a unique territory revealing a deeply curious mind, and an master craftsman whose care and regard for the worlds of his stories imbues them with a rare authenticity. From the animistic tales of Adivasi tribespeople,and the interplay of complex relationships between broken people, to the complexities of lives lived on the fringe, Alam is able to create characters and events that function on the level of myth and archetype.

As we navigate Alam’s complex, intricate fictional worlds, we encounter both a multitude of emotional universes imagined or drawn from keenly observed life, and nightmarish abstractions.

Chinese

23. Mother River

By Can Xue

Translated by Karen Gernant

The thirteen stories in this collection are vintage Can Xue. Similar to her novels (The Last Lover, Frontier) and other collections (Vertical Motion) the focus is less on what happens and more on the experience of reading.

“Mother River” is a short bildungsroman of a young man who decides to become a fisherman (and crafter of spherical maps) and discovers that performing the role itself is more important than the number of fish they catch.

Surreal, provocative, and unique, Mother River reinforces Can Xue’s status as one of the most reward and complex writers working today—and a perennial favorite to win the Nobel Prize.

Catalan

24. The Fake Muse

By Max Besora

Translated by Mara Faye Lethem

The Fake Muse, Max Besora’s follow-up to the wild—and wildly beloved—The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia, creates a kaleidoscope of absurd situations that, for even more absurd reasons, end up exploding in uncontrolled violence.

A novel full of humor that begins as a collection of short stories but which, little by little, builds into a choral work, made up of a variety of characters and various literary genres, all of which demonstrate Besora’s fantastic imagination and skill as a writer. This culminates in an unforgettable scene in which the protagonist of the book turns the tables on the author and calls into question his motives, why he chooses to create particular subjects for his books and, above all, his responsibility for how he treats them.

Finnish

25. Lowest Common Denominator

By Pirkko Saisio

Translated by Mia Spangenberg

Writing in the wake of her father’s death, the narrator of Pirkko Saisio’s autofictional novel transports us to the 1950s Finland of her youth, where she navigates life as an only child of communist parents. Convinced she will grow up to become a man, a young Saisio keeps trying and failing to meet the expectations of the adults around her. Writing with her trademark wit and style, each formative experience—with the Big Bad Wolf, a bikini-clad circus announcer, and Jesus Christ “who has a beard like a man but a skirt and long hair like a woman”—drives her further and further from her family and others. Struggling to understand her place in the world around her, it’s in language that she discovers a refuge and a way to be seen at last.

Swedish

26. Ixelles

By Johannes Anyuru

Translated by Nichola Smalley

Ruth lives comfortably with her son, Em, in a house by the sea. She has a well-paying job at the Agency, a firm that creates elaborate fictions to shape public opinion. Their lives weren’t always like this. Ruth had to get Em out of Antwerp’s hopeless postal code Twenty-Seventy, the neglected neighborhood where Em’s father, Mio, was murdered when she was still pregnant. A new assignment forces her to return to the place she once called home, and she’ll need to convince old friends and family—the only people in her life who connect her to her past—to remain silent as the government demolishes it all. Amid this upheaval, Ruth discovers a golden CD with a voice on it claiming to be Mio. He is in a place called the Nothingness Section, which may be an island or just another piece of fiction. In Anyuru’s story of stories, are there any tales where Mio can end up with Ruth, raising his son by the sea?

Croatian

27. Celebration

By Damir Karakaš

Translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać

Mijo, a soldier in the Nazi-allied Ustaša force, has returned to his village at the end of the war. He’s hiding in a hole in the woods, watching as the soldiers who want him dead return again and again to his house, disturbing his wife and children at all hours of the day. If he can just wait long enough, he naively believes, the atrocities of the war and his own involvement in it will be forgotten, and he can have what he really wants: a quiet life farming his land with his family.

How did Mijo become the man we encounter in these pages? By facing poverty? Enduring heartbreak? Nurturing ignorance? Damir Karakaš, a war reporter who witnessed the horrors of the breakup of Yugoslavia firsthand, examines the recent history of an unsettled region in evocative prose, contrasting the beauty of nature against the failings of people. Celebration, translated by the incomparable Ellen Elias-Bursać, traces a dark path—from hapless individual to world-changing catastrophe—in search of a way to break the cycle of political violence.

German

28. Under the Neomoon

By Wolfgang Hilbig

Translated by Isabel Fargo Cole

An abandoned construction site. Glowering pits and furnaces. A lone man in a bungalow. Widely considered to be one of the great German writers of the twentieth century, Wolfgang Hilbig’s dark visions have long held readers aloft with their musical language and uncompromising assessment of the modern world. In Under the Neomoon, his debut short story collection originally published in East Germany in 1982, Hilbig’s persistent fixations—factory pits, rampant nature, and split identities—are at their most visceral and brilliant. Rendered into English by Hilbig’s longtime translator Isabel Fargo Cole, these short tales apply fluorescent language (“garlands of cast-iron flowers,” “tall dark-green water grasses”) to lives and spaces of foreclosed dreams. An electric collection that evokes the works of Andrei Tarkovsky and Ingeborg Bachmann, Under the Neomoon is a neon-bright reminder of the importance of storytelling from down below, where the workers toil.

Dutch

29. Off-White

By Astrid Roemer

Translated by Lucy Scott and David McKay

It’s 1966 in Suriname, on the Caribbean coast of South America, and the long shadow of colonialism still hangs over the country. Grandma Bee is the proud, cigar-smoking matriarch of the Vanta family, which is an intricate mix of Creole, Maroon, French, Indian, Indigenous, British, and Jewish backgrounds. But Grandma Bee is dying, a cough has settled deep in her lungs.

The approaching end has her thinking about the members of her family she’s lost, and especially one of her favorite granddaughters, Heli, who has been sent away to the Netherlands because of an affair with her white teacher. Ultimately, there’s only one question Bee must answer: What is a family? If her descendants are spread across the world, don’t look similar, don’t share a heritage, and don’t even know each other, what bond will they have once she has died?

A moving portrait of a woman finding peace in the legacy that is her daughters and granddaughters, Off-White, keenly translated by Lucy Scott and David McKay, is also a searing and complex portrait of male violence, the legacy of colonialism, and a dismantling of what it means to be “white”. Written after a nearly 20-year break from publishing, Off-White is another masterpiece from the only Surinamese author to win the prestigious Dutch Literature Award.

30. The Third Temple

By Yishai Sarid

Translated by Yardenne Greenspan

In a near-future Jerusalem, harrowing omens plague the city: a desecrated altar, an unbearable stench, a rampant famine. Shaken but devout, Jonathan, the royal family’s third son, continues to hold services and offer animal sacrifices at the prophesied Third Temple, built to consecrate the founding of the new Kingdom of Judah. His father, Israel’s self-appointed king, has abolished the Supreme Court. The Torah is the law of the land, and only people of the Jewish faith are allowed in. When war breaks out and an angel of God begins to torment Jonathan, warning him of his father’s sacrilege, the foundations of the young priest’s faith—and then his world—begin to give way.

Winner of the prestigious Bernstein Prize, The Third Temple plunges readers into a tempest of fanaticism, betrayal, and destruction. Where does the power of man end and the power of God begin? With chilling resonance, this vivid novel from one of Israel’s leading authors sounds an unforgettable warning amidst rising extremism.

As you explore this curated list of books translated from a variety of languages, you may encounter both familiar names and new, intriguing titles. Each book on this list offers a unique perspective, whether it’s from a language you’re already acquainted with or one that’s new to you. We hope this selection sparks your curiosity and adds a fresh layer to your reading journey. Have you discovered a new addition for your to-be-read list? May these stories broaden your horizons and enrich your literary adventures.