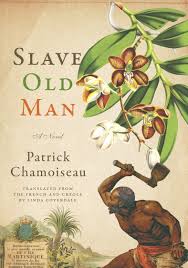

Slave Old Man

By Patrick Chamoiseau, Linda Coverdale (Translator)

We follow them into a lush rain forest where nature is beyond all human control: sinister, yet entrancing and even exhilarating, because the old man’s flight to freedom will transform them all in truly astonishing—even otherworldly—ways, as the overwhelming physical presence of the forest reshapes reality and time itself. Chamoiseau’s exquisitely rendered new novel is an adventure for all time, one that fearlessly portrays the demonic cruelties of the slave trade and its human costs in vivid, sometimes hallucinatory prose. Offering a loving and mischievous tribute to the Creole culture of Martinique and brilliantly translated by Linda Coverdale, this novel takes us on a unique and moving journey into the heart of Caribbean history.

About the Author: Patrick Chamoiseau

Patrick Chamoiseau is the author of Texaco, which won the Prix Goncourt and was a New York Times Notable Book, as well as Creole Folktales and Slave Old Man (The New Press), among other works. He lives in Martinique.

Read an Excerpt

The old man ran. He quickly lost his hat, his staff. He ran. Ran without haste. A steady pace that took him surefooted through the back-of-beyond zayonn undergrowth. He sent his body across dead stumps, laid low the kneeling branches with his heels, hurtled down reclusive ravines devoted to pure silences. Around him, everything shivered shapeless, vulva dark, carnal opacity, odors of weary eternity and famished life. The forest interior was still in the grip of a millenary night. Like a cocoon of aspirating spittle. Another world. Another reality. The old man could have run with his eyes closed: nothing could orient him.

Sometimes he bumped into unseen little branches, his toes, ankles, face—whipped! He had to run behind his bent forearm to protect his open gaze. Then, as he went on, the trees drew closer together in the thickest of pacts. The boughs fastened themselves to the roots. The raziés-underbrush gave lavishly of its irritating prickles. The Great Woods loomed. His pace slowed. At times he had to crawl. The enveloping vegetation stuck to him, sucking, elastic. With bleeding elbows, step by step, he made his way. It went up. It went down. It monta-descendre : up-and-downed. Sometimes, the ground disappeared. He tumbled then into sheets of cold water that gurgled with emotion.

The old man felt close to the sky. The stars diffused a blissful radiance etching the forms of the ferns. But the darkness—so intense—sent that pallor to him in a starry dust: it dissolved all forms. Often he headed down again, he had the impression of descending endlessly, of reaching even the fondoc-fundament of the earth. There he thought to find the vomiting of lava or the fires said to flame from the foufoune-pudenda of femmes-zombis.

The torn rachées of his heart throbbed within him, stirring liquid, glowing embers that shattered his body to rejoin the sky. Such incandescence summoned up wild earthy fumes in his bones. Leaves, roots, trunks, took on the odor of ashes graced with those of green corn and newborn buds.

Continue Reading…

Article originally Published in the October/November 2019 Issue “Read Global”